Review by Andrew Swafford

Walking into The Boy and the Heron was a little surreal: I couldn’t believe I was getting a chance to see a new film by Hayao Miyazaki. Perhaps the greatest animator in film history, Miyazaki is in his eighties and has announced his own retirement numerous times – and the last time, it felt real. The Wind Rises, released ten years ago at this point, was a profoundly melancholy film, a bittersweet reflection on a storied career that could only have been made by a great artist with a complicated relationship to his own work. It felt less like a typical Studio Ghibli fantasia and more like something Miyazaki needed to get off his chest: a personal admission to his audience that making art on an industrial scale comes with a moral cost. It was personal and powerful, but more importantly it felt final; it was a film that felt intended to be a filmmaker’s last film. What could possibly follow it?

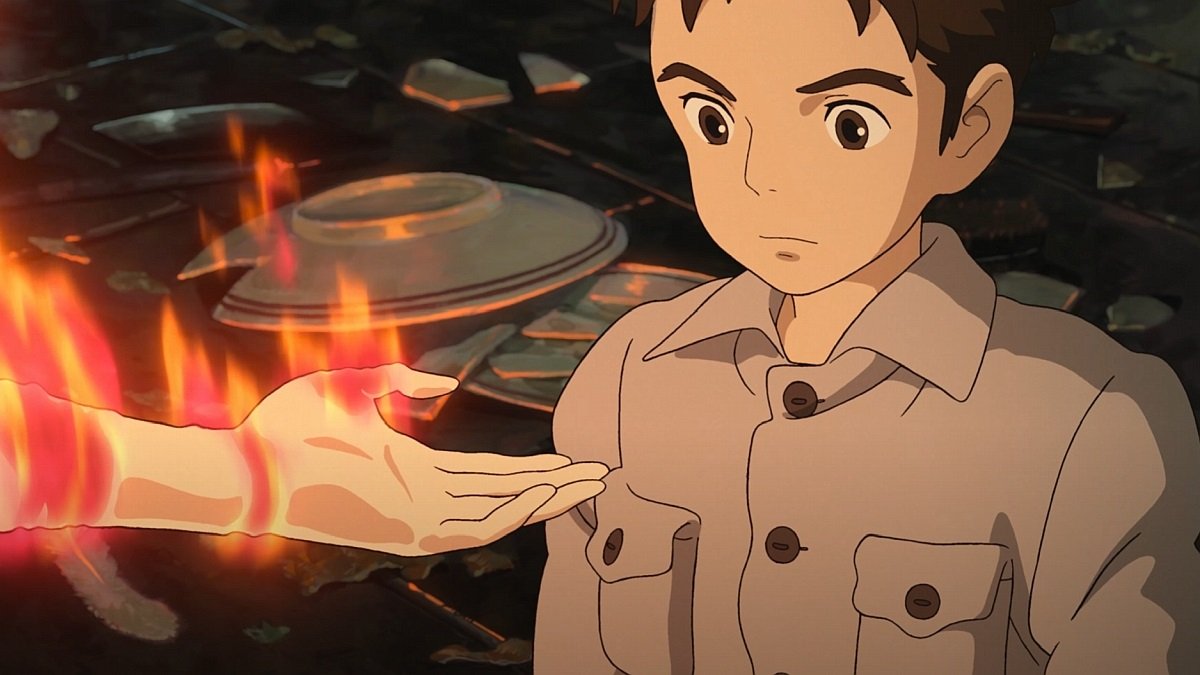

A return to old-school Miyazaki magic, apparently: The Boy and the Heron is an idiosyncratic fairy tale about a grieving child who follows a strange bird into a portal to another world. The film’s narrative engine runs on so much dream logic that I can’t even fathom a clear way to explain much more beyond that, and it’s a wonderful feeling to have no idea where this old storyteller’s new yarn is going. Jam-packed with bizarre imagery and singular artistic flourishes, The Boy and the Heron is a reminder that what viewers love about Miyazaki is his boundless imagination. Much of what Miyazaki dreams up can be quite disturbing, as well: one early fantasy sequence involves a river full of dead-eyed fish chanting menacingly for the young protagonist to join them underwater, and the titular heron goes from strange to grotesque as a human face begins crawling out of its mouth.

As the film progresses, the realm of the possible expands further and further until the bounds of fiction themselves are approached: late plot developments involve an encounter with Miyazaki’s own author avatar, and the old man offers the keys to his kingdom of dreams and madness to his heir apparent, but only after imparting important wisdom about the value of personal uniqueness. The only true antagonistic force in The Boy and the Heron is an army of goose-stepping parakeets who all look identical to one another save for their pigmentation, which reads to me as the way Miyazaki sees the rest of the children’s entertainment landscape: bright and colorful, but ultimately conformist and devoid of soul. The advent of AI-generated art threatens the validity of human creativity even more than the endlessly brand managed (and Disney-dominated) animation industry already was. Perhaps Miyazaki has returned as a response to some perceived crisis of creativity – though Miyazaki appears to still have it in spades, especially if recent reports of him tossing around even more ideas for new films at the Studio Ghibli offices are to be believed.

I don’t think The Boy and the Heron feels like a swan song quite in the same way that The Wind Rises did; instead, it feels like a film by a man who feels newly energized and ready to make a lot more. I dearly hope that Miyazaki gets many more years to pursue his imagination.