Review by Zach Dennis

1996 was a different time.

That’s a bit of an understatement, but it doesn’t sully the truth either. When Space Jam (1996) came out, it didn’t matter if you were the most die-hard basketball fan, a casual television gazer at your local bar or a complete agnostic to the game – you knew who Michael Jordan was.

A handy reminder came last year with the ESPN-produced documentary series, The Last Dance, which not only revived the mythology of the 1990's Chicago Bulls but also the full-scale pop culture impact of Jordan.

Michael Jordan and the 1991 Chicago Bulls.

Logically, it makes sense: there weren’t that many forms of media to consume in 1996. You could turn on the television, pick up a newspaper or magazine, switch on the radio and maybe, if you were particularly tech savvy, maybe frequent a chatroom on the world wide web.

Regardless of your mode of cultural consumption, you probably ran into Michael Jordan. Hanes ads on TV and in magazines, articles in the newspaper ranging from his basketball exploits to the tabloids on his home life and personal entanglements. Radio shows were dedicated to the dissection of everything Jordan.

Oh, and let’s not forget his name is literally a brand.

All of this is to say, there was no escaping Michael Jordan in 1996, so when Space Jam came out, it was rightfully about how much we all love (and kind of want to be) Michael Jordan.

Rewatching the movie, it’s clear adoration of the Jordan brand propels the movie. The plot centers around Jordan’s (real-life) departure from playing professional basketball and his pursuit of a career in Major League Baseball. In the Space Jam reality, Jordan is struggling with his new pursuit and is reluctantly (by way of cartoon hook) pulled into the world of the Looney Tunes, who themselves are at a crisis point when a visiting alien contingent wants to whisk them back to their home planet to use them as exhibits at their intergalactic theme park. The Tunes will go, but only if the aliens beat them at a game of basketball. The aliens cheat, electing to steal the powers of notable NBA players such as Charles Barkley and Patrick Ewing, and come to the game as formidable foes. All that become moot by the end, as the Tunes are able to persuade Jordan to dust off his North Carolina shorts and join them for the basketball game – securing their freedom, re-igniting Jordan’s passion for basketball, and leading him to return to the Chicago Bulls. (It’s no secret that Jordan was making this move with mythic basketball training camps and pick-up games happening on the Warner Bros. lot at the same time of the filming of the movie).

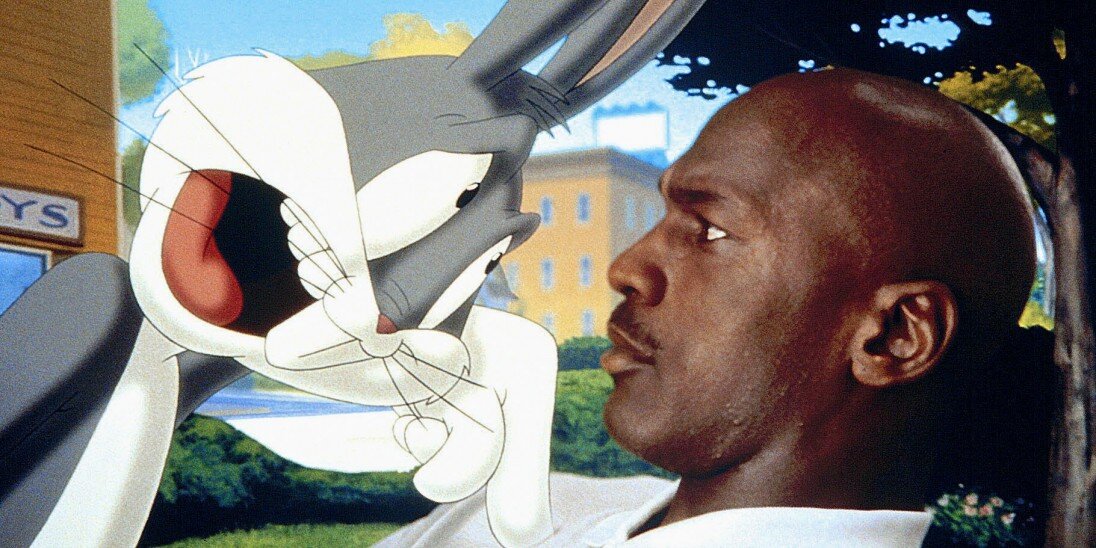

Bugs Bunny and Michael Jordan in Space Jam.

It’s tough to say if the narrative behind the new Space Jam sequel and its star – Los Angeles Lakers forward LeBron James – quite mimics that of its predecessor. While on the court, James has actively elicited comparisons to Jordan for his consistent dominance, I would wager to say that James lacks the clout of 1996-era Michael Jordan. Not only that, James doesn’t have the worldwide notoriety that Jordan did – and even still does.

In Space Jam: A New Legacy, James is struggling to keep a strong bond with his middle son, Darius (Ceyair J. Wright). Darius would much rather be refining his basketball video game skills than following his father’s desires and playing on an actual court. The friction bubbles to the surface when Darius tags along with his dad to a meeting at Warner Bros. where executives pitch James on their latest creation – “Warner Bros. 3000,” an algorithm-based system that would allow King James to produce his likeness (or cartoon likeness) into any Warner Bros. property of his choice. LeBron racing in a Qudditch match in Harry Potter? Sure. LeBron riding a dragon in Game of Thrones? Easy. Even LeBron crooning in Rick’s bar in Casablanca is on the table, should that be desired.

The entire apparatus is the brainchild of an algorithm known as Al G. Rhythm (played by Don Cheadle), who is hoping to parlay the visibility and popularity of James into blasting his vision into the stratosphere. “He has millions of social media followers from all over the world hanging on his every word,” Al remarks when daydreaming of the possibilities between himself and the Lakers star.

Unfortunately for Al, James rejects the offer. But the algorithm isn’t something restricted to just one device. Al has access to an entire universe of Warner Bros. properties and vaults LeBron and Darius into “the Serververse,” a digitally contained amalgamation of all things WB. Now trapped, James is given one option: play Al and his team in basketball and if he wins, he can get his son back. If he loses, he has to live in the Serververse and, I assume, pop up in everything Warner Bros. for the rest of eternity.

The formula is much the same: LeBron has to team up with the Looney Tunes to face Al and his team of NBA-infused avatars. But now the brand isn’t the movie’s star. It’s everything else that Warner Bros. owns – and then some.

Regardless of how you assess the basketball accomplishments of Michael Jordan and LeBron James, Space Jam: A New Legacy makes it clear that they aren’t the same in terms of notoriety, or maybe, that notoriety has shifted from the physical star to the accumulated properties around them.

It’s been remarked on since the announcement of the movie that Space Jam: A New Legacy is far from the first movie to lean on references to its studio’s other properties. As some have pointed out, the Looney Tunes themselves specialized in riffing off other Warner Bros. programs and stars – but that wasn’t necessarily the case for long, as Peter Labuza remarked in a tweet contributing to the discourse.

In this case, it becomes less about the fact that a character from Harry Potter can whiz past LeBron on a broomstick as he wanders the world or the gang from A Clockwork Orange can inconspicuously pop up in the audience of the film’s climactic game. Instead, it is more about what these figures mean in place of any actual narrative.

Let’s play where’s the provocative characters from the Stanley Kubrick film in a Warner Bros. family film

It’s not as if anyone expected the plot of Space Jam 2 to be a particularly clever concoction, but there’s a difference between constructing a narrative that doesn’t coalesce together and piecing together references to other icons that the audience would recognize in order to continue to keep them interested.

When the majority of the plot contains James and Bugs Bunny jumping from Warner Bros. property to Warner Bros. property in order to find the rest of the Looney Tunes, it’s less of story beat and more of a recognition-based dopamine hit that is meant to evoke the audience’s love for Harry Potter, Game of Thrones or Mad Max: Fury Road.

While the characters and properties evoked in Space Jam: A New Legacy are American, their use and relationship with the audience feel in line with Japanese otaku culture, and specifically the research done by Hiroki Azuma in his seminal book, Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. In the book, Azuma details how this certain characters and properties gained prevalence in postwar Japan and how these characters display a sacrifice of a search for greater significance in favor of instant gratification.

In short, these characters became beloved and audiences developed a devout relationship to them, making their very appearance a satisfying experience rather than any attempt to develop some sort of narrative structure around them that feigns for a greater meaning. The book presents a quote from cultural critic Okada Toshio (writing in the same year as the original Space Jam’s release), who presents a redefinition of otaku as a “new type of person responsive to the cultural conditions of a highly consumerist society.” In this assessment, he tried to shift our understanding of otaku as something more than subculture outcasts enjoying pop entertainment – rather, Toshio wanted readers to recognize that these types of cultural consumers are growing more rapidly and responding to content in a way unlike ever before.

Azuma goes on to examine a concept investigated by French sociologist Jean Baudrillard who predicted that original and copied products would lose any distinction from one another. The term, known as simulacrum, would make neither the original product or the copy as the dominant form – they would both exist on the same plane. Critic Nakajima Azusa added that “the otaku choose fiction over social reality not because they cannot distinguish between them but rather as a result of having considered which is the more effective for their human relations, the value standards of social reality or those of fiction.”

In a way, this reading explains the line of thinking behind Space Jam: A New Legacy, an accumulation of one studio’s simulacrum into one confined space and anchored by a recognizable figure. There isn’t any reason for Pennywise from IT to be in the audience of the basketball game other than for the audience member’s brain to register this character and elicit that serotonin response that comes along with recognizing iconography from popular culture.

In the movie, a lot of the friction between LeBron and Darius hinges on the former’s misunderstanding of the latter’s passion for video games. In Darius’s game, everything looks like a real basketball court, but the apparatus is also elevated with power-ups and extra style point rewards along with the two and three-point shots more closely associated with the game. By the end of the movie, LeBron has come around to Darius’ version of the game because he realizes that in the end, it is all about having fun.

But this decision also speaks to Nakajima’s point that selecting fiction over social reality has become the norm. Darius’ version of basketball – one that feels more infused with NBA 2K and even NBA Jam culture – is much more synonymous with the intended audience than a traditional game of basketball. Counter to his predecessor, James is deferring to the audience desires rather than staking his claim for his version and showing that it is the greater form with him at the height of his powers as Jordan did in the original.

And that just might be what Space Jam: A New Legacy is about, overall. The brand is no longer the individual associated with the product, but the individual’s proximity to other IP beloved by the otaku-like audience that’s watching. It’s no longer about reveling in the star power, but making sure you have the developed knowledge and appreciation to understand what is developed alongside it.