Festival Coverage by Miranda Barnewall

Back for its sixth year, the Wexner Center for the Arts, located in the heart of The Ohio State University’s campus, hosted its annual film festival, Cinema Revival: A Festival of Film Restoration. As the name implies, this festival is a celebration of film preservation and screens recent preservation projects from the past year. Included in the festival’s program are discussions of techniques and challenges in film preservation. I was lucky enough to attend the majority of the festival (Thursday through Sunday), and have chosen to talk about the films and events that struck me the most. Because this festival is focused on preservation, I talk about the preservation issues and explanations surrounding these projects when possible.

Shorts and Special Presentations

Jammin’ the Blues

White folks call it madness but we call it Hi De Ho: An “All Colored” Vitaphone Program

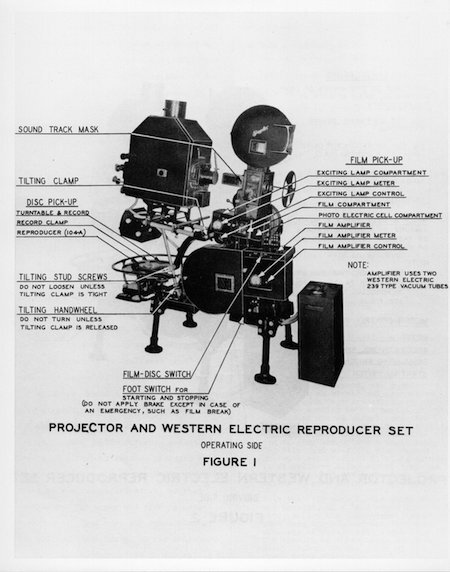

Curated and introduced by Ina Archer, an artist and a Media Conservation and Digitization Assistant at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, this program screened ten selected Vitaphone musical shorts ranging from 1923 to 1944. But what is the Vitaphone? The Vitaphone was a sound-on-disk motion picture system, rather than the later standardized sound-on-film. The sound was recorded on a 33 ⅓ rpm shellac disc during recording, and then for projection, a duplicated record was placed on a record player that was synchronized with the film projector. Archer’s interest in the conception of the Vitaphone was its relation to vaudeville, particularly black performers of the time.

Ranging from ten to twenty minutes in length, these shorts mainly function to showcase talent acts rather than tell a well-rounded story. Indeed, the plots are quite thin, and many shorts reuse the same tunes (St. Louis Blues, Tiger Rag, etc). The exception to this in the films showcased was The Black Network, starring Nina Mae McKinney. This twenty minute short depicts one day of recording at an all-black radio station. The premise is that a wealthy shoe polish company owner agrees to sponsor a radio show that will showcase the vocal talent of Nina Mae McKinney and Babe Wallce; however, the sponsor’s wife is determined to perform on the show and does, much to McKinney’s disapproval. While its plot is still loose in some places, its structure reminded me of a fast paced, Warner Bros. pre-code type of comedy. Had it been able to be a feature-length film with a plot to support the acts (and removal of racists stereotypes) I believe it would have been a good feature. But again, this is mainly about the acts within it & the entertainment.

The most unique short of this lineup, and my personal favorite, was Jammin’ the Blues. Directed by the well-known photographer Gjon Mili and cinematography done by Robert Burks, this short exudes the pure coolness and sophistication of jazz at the time. Shot in lush, smokey black and white with striking compositions, we get to see jazz great Lester Young, cigarette in hand, play his saxophone with his band mates. It’s truly like nothing else; in fact, this short was added to the National Film Registry in 1995.

Other notable acts featured in the shorts presented included the Nicholas Brothers, Noble Sissle, Cab Calloway, Cora La Redd, and James P. Johnson.

Home movie footage of Hedy Lamarr

Hollywood Home Movies from the Academy Film Archive (1931-1970)

To many people, the idea of watching home movies sounds boring. How many times have you seen a group of friends go on a picnic on a sunny day? You don’t know those people, so it can be difficult to care. But what if that group of people included Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Ray Milland, and Ann Southern? This is just what the Hollywood Home Movies from the Academy Film Archive program offered.

While we were able to see many home movies, I will name just a few that I particularly enjoyed. These included vacation footage of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. and Marleine Deitrich who lovers at the time, Fred MacMurray and his wife playing with some puppies on the lawn of their Hollywood home, Fred Zinneman, his wife, Renee, and son in Cannes for the festival, and footage of Shirley Temple on set of Heidi getting butted by a goat multiple times for one take. With these home movies, we’re able to see the actors as they really are.

In addition, these home movies can be glimpses into the production of movies and the film technology at the time. For example, one 8mm home movie shows a Three-Strip Technicolor camera shooting Vivan Leigh in the barbeque scene for Gone With the Wind (1939). Another home movie from Jerry Lewis’ collection shows a VistaVison camera off to the side of the frame as Jerry jokes with director Don McGuire on set of The Delicate Delinquent (1957). (I must say, it seems Jerry was doing a lot of joking on set - how did they even get that movie finished?!).

The screening wouldn’t have been complete without the live accompaniment by Sue Harshe and narration by Mike Pogorzelski, who supplemented the screening with various facts and tidbits about Hollywood employee’s lives, some of which I noted above. It's such a treat that the Academy Film Archive screens the many home movie collections of Hollywood industry people when they can. In fact, each Hollywood Home Movie presentation is completely different, so if you are able to attend two of Hollywood Home Movie screenings, you will not see the same program twice! If you are ever able to check out a presentation of some movies from the home movie collections, I highly recommend it.

A Star is Born

The Technicolor Reference Collection - A 1950s Survey

The Technicolor Reference Collection is an example of the importance of film conservation. This collection was housed at Technicolor until they closed in the 1970s when someone called the Academy to ask if they wanted the reels; otherwise the reels were going to be pitched. The Academy accepted the offer and took the reels.

While the person is unknown, it is clear that these select reels were approved by someone for reference whenever new prints of films needed to be created. While the Technicolor dyes are stable, not all the Technicolor prints that were created were consistent. Because they were to be used as reference, these reels were, under absolutely no circumstances, to be sent out for projection. This order was ensured by snipping out some sections of the reel and splicing slug (blank film) in its place. Further, while it’s assumed there were reels from the 1930s and 1940s (the nitrate era), the only reels that exist are from the 1950s (the safety/acetate era).

The lineup was a fantastic example of showcasing what Technicolor could do. The contrast between two westerns, such as Silver Loda with its “Technicolor look” and Rio Bravo, owning a muted, sepia toned look. In addition to the Academy ratio (1.37:1), Technicolor was utilized on widescreen formats, as well, as seen in the excerpts from A Star is Born and Battle Hymn.

Today, these reels are often used as reference points for studios or companies working on a restoration to ensure they achieve proper color grading. However, while we are lucky to have the option of 4K restorations today, in my opinion there is nothing like seeing an imbibition Technicolor print projected. What a treat!

Feature Length Films

Speed (Jan de Bont, 1994, USA, 4K DCP)

You might be thinking that Speed (1994) may seem a little too new or widely-seen to be included in such a festival. Well, not necessarily. While creating the program for the festival, Dave Filipi, curator of Cinema Revival and director of Film/Video at the Wexner Center, soon realized after talking to some people about Speed, many people hadn’t seen it, myself included.

I highly recommend you read Reid’s fantastic review of Speed (1994). As a person who is typically never drawn to action packed movies, I freaking loved this. I was stressed out the entire time even though I knew they would be okay. I was blown away by all the effects and stunts, especially the subway coming up onto the city street. Maybe it’s because these were live action rather than CGI effects, or the potential reality of the situation. Its conflict is grounded in reality, not in a Marvel-type universe where the goal to save the world is so abstract to me that the stakes don’t seem real.

Instead of having a broad “save the world” conflict, this film is concerned with the safety of the everyday citizens. Though the riders’ lives aren’t explored, we learn enough to care about them and root for them. As the film progresses and tension heightens, everyone bands together to save one another. Simply, it’s the empathy and understanding for others who are different from us and building that connection, and I’m a sucker for that. And not just the riders, but also Jack (Keanu Reeves). His patience and calm, supportive demeanor, even though there is a literal bomb under the bus, is mind blowing to me. I don’t know if there will be another action movie that I love as much.

Ride Lonesome’s original camera negative (OCN)

Ride Lonesome after digital restoration

Ride Lonesome (Budd Boetticher, 1959, USA, 4K DCP)

Directed by Ohio State University alum Budd Boetticher, Ride Lonesome is one of the five films Budd Boetticher made with actor Randolph Scott, executive producer Harry Joe Brown, and screenwriter Burt Kennedy. Ride Lonesome’s premise is rather simple: When bounty hunter Ben Brigade (Randolph Scott) comes across a killer wanted in Santa Fe, Billy John (James Best), Brigade decides to take him to Santa Fe. It’s later revealed that the reason Brigade escorts Billy John to Santa Fe is because he wants to take revenge on Billy John’s brother, Frank, for hanging Brigade’s wife years ago.

As one who doesn’t often turn to westerns, I found this to be a decent, entertaining (and quick 73 minutes) western. However, it was the preservation of this film that interested me the most. Given its low budget, Ride Lonesome was shot in Eastmancolor and its original camera negative (OCN) was used as the duplicating element to create new prints and negatives. (In a typical production workflow, a duplicating element, called a fine grain, is created to be used to strike duplicate negatives, and from that dupe negative create new prints. For color films, black and white separations of the green, red, and blue records are used as preservation masters. Ride Lonesome did not have black and white separation records made.)

This left the film faded and in a rather battered condition. In photochemical restoration, there was only so much one could do in a restoration. However, with digital, it brought about “a new wonderful toolbox” for film restoration, according to Grover Crisp of Sony Pictures, who supervised Ride Lonesome’s restoration. Mr. Crisp presented a few examples of before and after pictures of selected frames and tears from Ride Lonesome that were able to be corrected due to the wonders of digital technology. Indeed, the fantastic restoration done on Ride Lonesome shows why we should embrace and appreciate digital’s entrance into the world of motion picture film.

I’m No Angel (Wesley Ruggles, 1933, USA, 4K DCP)

“When I’m good, I’m very good. When I’m bad, I’m better.” So goes the famous quote, which is spoken by Mae West in I’m No Angel. Said to have saved Paramount Studios from bankruptcy in the 1930s, it's even more impressive that Mae West was credited as creating the story and writing the screenplay and dialogue for I’m No Angel. Tira (Mae West) is a performer in a traveling circus, first as a shimmy shaking, mind reader to a lion tamer who can put her head in the jaws of the lion. This new routine as a lion tamer brings her much fame and takes the show to New York City. With fame comes the opportunity to meet many wealthy men. She eventually meets Jack Clyaton (Cary Grant), the cousin of Tira’s current flame, and the two begin a relationship.

I don’t know if I’ve ever seen anything like I’m No Angel. There is something so absolutely unapologetic about Mae West’s whole manner. She knows she’s bad and she doesn’t care; in fact, she likes it. She will use men to gain the lavish lifestyle she desires. It’s something that, I think, as someone who says, “I’m sorry,” at least ten times a day, needs to see every once in a while. Another interesting thing of note is that Tira’s maids are on-screen for a good portion of the film, something I don’t recall seeing in other pre-code films of the time. Rather than simply just being maids, they’re also Tira’s closest friends. I encourage you to seek out I’m No Angel, or at least one Mae West film, to get a sense of what her world is like.

Moulin Rouge (John Huston, 1952, UK, 4K DCP)

John Huston and his cinematographer Oswald Morris took a bold step when creating the palette for the 1952 film, Moulin Rouge. Rather than employing the typical eye-popping, bright colors associated with Technicolor, which Huston disliked, Huston and Morris went with a more muted, subdued color palette, particularly for the scenes in the Moulin Rouge.

Moulin Rouge tells the story of the life of the famous French artist Henri de Toulouse-Laterrec (Jose Ferrer) in late 19th century Paris; his challenge is finding true love, which he finds to be difficult as being someone who stands four foot six inches tall. Laterrec’s creation of the famous Moulin Rouge poster poses as the time frame for the film, opening with Laterrec sketching the beginnings of his famous Moulin Rouge poster and ending with the poster’s popularity raising the Moulin Rouge’s profile, as well as Laterrec’s popularity. Yet popularity in the art world does not equal happiness. Rather, throughout much of the movie, Laterrec is a lonely, depressed figure who longs for romantic love. Before rising to fame in the art world, Laterrec finds himself in a tumultuous, unhealthy romantic relationship with a prostitute, Marie Charlet (Colette Marchand). When she finally leaves him, Laterrec begins to attempt suicide but stops when he sees his unfinished Moulin Rouge poster. He picks up his brushes and finishes the poster.

This movie is quite bleak, and the character of Laterrec is someone who, at times, you root for and at other times wish he would just open his eyes to what is in front of him. Moulin Rouge was restored last year by The Film Foundation in partnership with many other associations. If you get the opportunity to see this, I recommend it.

Go West (Buster Keaton, 1925, USA, 4K DCP)

What isn’t there to say about this Buster Keaton film? While it certainly isn’t Keaton’s best film, it certainly is quite sweet and one that any animal lover would enjoy. Unable to find a job in his town or make any friends, Friendless (Buster Keaton) sells his belongings and hops on a train to go west to make a fortune. Midway through his journey, Friendless falls off the train and soon finds himself employed as a cattle rancher. It’s here that Friendless makes his first friend, Brown Eyes the cow.

Go West is simply a sweet movie, with a good number of laugh out loud moments. However, it drags a bit towards the end when Friendless takes thousands of steer to the L.A stockyards to save the cattle ranch from going under. Recently restored by the Cohen Film Collection in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna at the L’Immagine Ritrovata in their series of Keaton restorations, Go West’s restoration was unique in that half of its original camera negative (OCN) is missing, and the rest of the reels contain some nitrate decomposition. With this restoration, they were able to use footage from other elements (nine elements total!) to replace the decomposing sections. The restoration looks great, and I recommend you check it out even if you have already seen Go West before.

Restored by the African Film Heritage Project

In mid-2017, it was announced that the Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI), The Film Foundation, and UNESCO (in partnership with Cineteca di Bologna at L’immagine Ritrovata) would collaborate to create the African Film Heritage Project (AFHP), an initiative to preserve Africa’s cinematic history. At the time, and even now, many of the classics of African cinema were and are unfindable and, thus, difficult to watch. To Souleymane Cisse, director of Yeelen (1987), it was an issue of losing cultural and historical reference and history for future generations. “If we don’t try and restore African cinema — made by Africans about Africans — then future generations will never know who they are,” Cisse told Martin Scorsese, founder of The Film Foundation, at Cannes in 2007.

The goal of the AFHP is locate and preserve fifty Afrcian films deemed culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant. As of now, four films have been preserved. Two films restored and preserved by The African Film Heritage Project were screened at the Cinema Revival festival, La femme au couteau (1969) and Muna Moto (1975). (You can find more information about AFHP here.)

La femme au couteau (The Woman with the Knife, Timité Bassori, 1969, Cote d’Ivorie, DCP)

Directed, written, and starring Timité Bassori, La femme au couteau is said to be his best film. Francoise Pfaff summarizes it as “the story of a Westernized Ivorian who seeks appeasement for his existential anguish and hallucinatory sexual fears through traditional Afraican healing and modern Western psychoanalysis.” It follows two different stories, one of the man who sees the vision of the woman with the knife, and the other of an older neighbor the man used to see in his neighborhood as a small boy who would go to the bars and talk about his time in Paris, France.

Director Bassori says, “La Femme au couteau is old traditional Africa who feels abandonded by her children and becomes as peevish as a possessive mother who uses threat to retrieve her stray offspring.” In the man’s apartment, we get medium static shots of his apartment with its modern 1960s bookcase, books, and a record player playing cool jazz. However, when outside his apartment, the camera is mobile, moving along with the character as he travels in the car, and captures the sites of Abidijan. The film reminded me very much of the French New Wave tradition; in fact, in some scenes you can see people watching as the camera films a scene. However, its central conflict, as well as Bassori’s directorial choices, are so unique that Bassori is able to stamp it as his own.

The structure of the film was unique so it took time to understand how everything pieced together. It’s a film that merits another viewing, and I hope to get the chance to do that soon, whether it be through streaming or another festival screening.

Muna Moto (The Child of Another, Jean-Pierre Dikongue-Pipa, 1975, Cameroon, 4K DCP)

Two weeks later and I still find myself thinking about Muna Moto. Cameroonian filmmaker Rosine Mbakam says Muna Moto plays on TV every Independence Day (the equivalent of It’s a Wonderful Life playing all day on Christmas Day in the US). However, Muna Moto carries so much weight for the country of Cameroon. Despite the strict censorship at the time, Jean-Pierre Dikongue-Pipa was able to create a film with a pointed commentary on the extreme, conservative restrictions the Cameroon government placed on its people, with particular focus on the dowry system.

Ngando and Ndome are young and very much in love. In order to marry Ndome, Ngando must follow the tradition of offering a (rather large) dowry in order to take her hand in marriage. Still living under his Uncle’s roof, Ngando is unable to come up with such a dowry and asks his Uncle for help. The Uncle, unable to have a child with any three of his wives, sees Ndome, a young, fertile woman, and believes she would give him a son. Ultimately, the Uncle is able to fulfill the dowry and marries Ndome.

Don’t think that Ndome has a quiet, soft spoken role in this film. She speaks out against her father when he says she will marry Ngando’s uncle, taking the lashings as necessary. She tells Ngando to sleep with her before marriage in hopes that she will not be able to marry Ngando’s Uncle. It is this event that causes Ndome to become pregnant, Ngando’s child.

It’s not simply just to be with Ngando, but also to preserve her freedom as a woman. Ngando and Nodme’s relationship is revolutionary, modern. At times, contemporary 1970s music plays as Ngando and Nodme spend time together.

Like La femme au couteau, it’s structure takes some getting used to to follow its plot. There are some gorgeous slow motion shots of Ngando and Ndome running along and playing on the beach. Their love is truly young love, each determined to do whatever they can to be with and support the other. Their love begs for a revolution of the traditional ways of Cameroon in favor of a more democratic society. Yet, their effort proves to be futile and too much for Cameroon.

Closing Thoughts

I had a wonderful time at this festival, and truly it is like no other. It’s a single screen festival so there is no rush to run to another theater in hopes of making it into the screening. Rather, it’s a small, cozy festival in which you can easily approach experts of the field and talk about the restoration work they’ve done and then turn to char with eager students with the hopes of entering the field themselves. I highly encourage you to look into attending this festival if film preservation is a particular interest of yours. I hope to see you next year!