Review by Michael O’Malley

Spoiler Warning

Content Warning: Rape

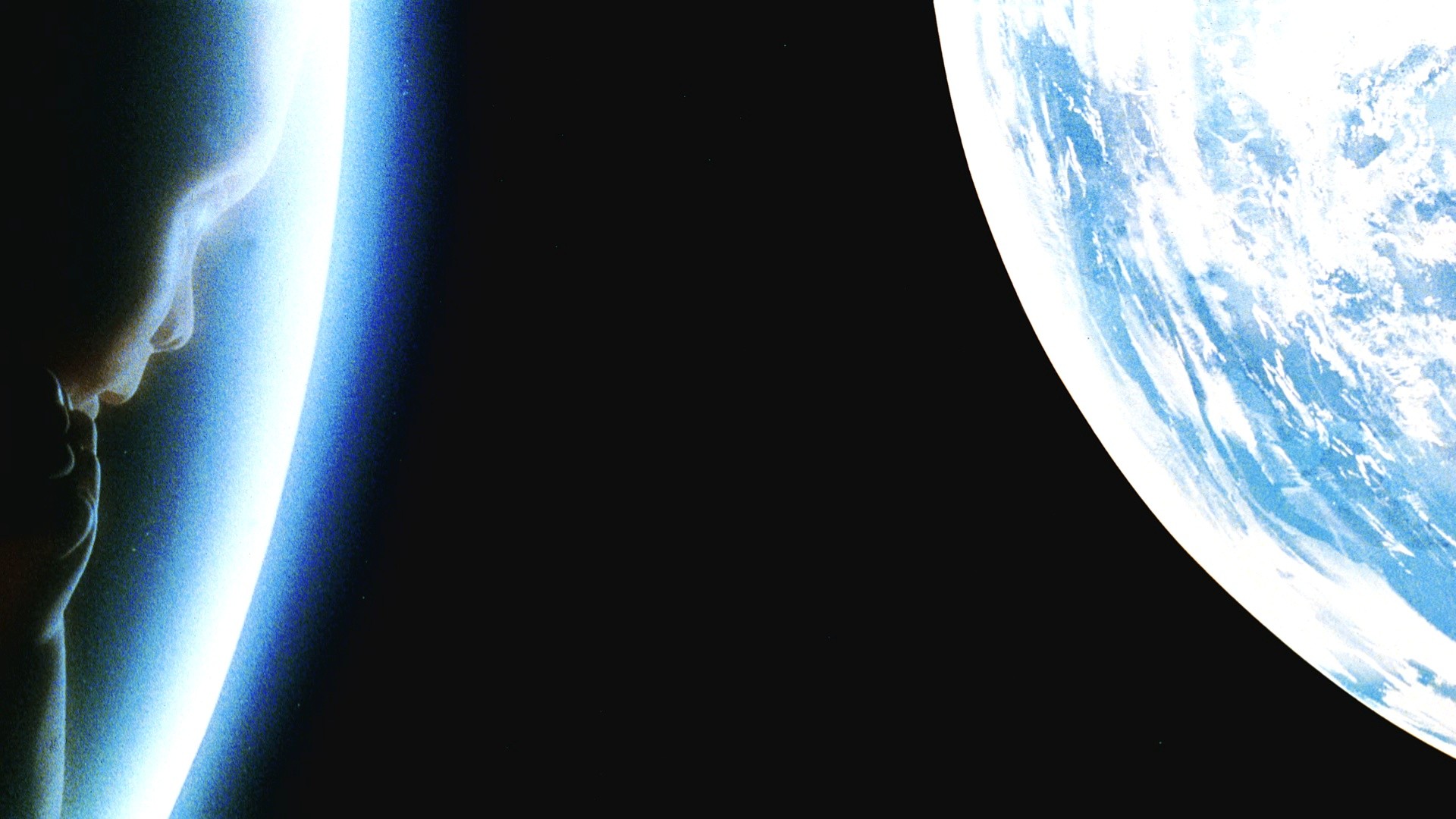

In some respects, the prospect of Claire Denis making an effects-heavy sci-fi space epic feels like a departure for the French arthouse auteur. It is her first science-fiction movie, as well as her first English-language movie, and one might be forgiven (though hardly correct) for guessing that this might be Denis’s reach for something approximating the contemporary mainstream. After all, it did (at least here in Knoxille) open alongside Avengers: Endgame, which I suppose could invite viewers to look for parallels between the two. But taken another way (a way that takes into account just how gobsmackedly brutal and strange this movie is), High Life fits pretty neatly within the tradition of “arthouse sci-fi” and even more neatly into the sub-category of “arthouse space voyage” that began, for all intents and purposes, with Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 in 1968 and continues on through (to name the two movies Denis seems most in conversation with) Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris in 1972 and Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar in 2014 (well, “arthouse”--definitely Nolan’s bid for the arthouse, if nothing else). Part of what’s interesting about this particular family tree of movies – 2001 through High Life – is the way that together they form a decades-long discussion about the nature of humanity’s relationship with itself and the way that relationship refracts and fractures when subjected to extreme isolation and eons of time. I mean, why make a big space movie if you aren’t going to ask the big questions?

Thus far, the discussion goes like this:

2001, with its aggressive otherworldliness, presents a universe entirely indifferent to the concept of an essential “humankind” and in fact argues (in typical Arthur C. Clarke fashion) that humanity is merely a story that conscious life tells itself, a mythological construct within life’s larger evolution toward a cosmic consciousness; humanity is, in the context of the film’s millions of years, only different in scale from the nonverbal ape and the cosmic-brained starchild, a blip that has absolutely no distinction within the cavernous structure of the universe. Then comes Solaris, which is something of a direct response to this philosophy. Its plot, which involves a space mission discovering a planet that physically manifests the psyche and memories of the mission’s crew members, takes almost the exact opposite stance to 2001. Instead of humanity being just a reframing of a larger, impersonal universe, Solaris shows the universe as just a reframing of humanity, reflecting and even becoming humanity. There’s a central irony to this idea in Solaris, that humanity is entrapped by its inability to see anything but itself in the universe around it (the decidedly ambivalent ending of the movie has one of the crew members abandoning the mission to stay with the planet’s hollow manifestation of his wife), but this irony is thrown out entirely by Interstellar, which takes the basic essentialist premise that Solaris develops about humanity and goes full-bore into a cock-eyed humanist mysticism. When Matthew McConaughey’s character travels through the black hole at the film’s climax and views the fabric of the universe beyond, he finds not an unknowable alien force, as in 2001, or an alien force aspiring to humanity, as in Solaris, but humanity itself, which has, centuries in the movie’s future, manufactured the black hole and the movie’s entire premise. The universe doesn’t just reflect humanity; the universe is humanity – actually, humanity is more than the universe. As the movie says in its oft-mocked finale, “Love,” the most human of forces, “transcends time and space.”

So where does that leave High Life? On the surface, High Life bears a lot of similarities to the most recent entry in the arthouse space voyage grapevine, Interstellar. Like Nolan’s film, High Life involves a scientific expedition to a black hole, demonstrates how the isolation inherent in space travel drives astronauts to increasing psychological extremes, and foregrounds a father-daughter relationship as one of its key emotional beats. But there are some important differences, too. The characters in High Life are death-row prisoners who are only on this voyage because of it is offered to them as an alternative to the death penalty; being prisoners, the characters are not scientists but guinea pigs, subjected to bizarre experiments that include exploitation their reproductive abilities to try to bring a baby to term in outer space; the daughter in the father-daughter relationship is the product of a rape that is a further corruption of an already horrific experiment.

This all gets at High Life’s biggest difference, not just from Interstellar but from the lineage of arthouse space voyage as a whole: High Life is obsessed with physicality: the blood, the guts, the saliva, and the sperm inherent in being human. For as much as the previous films have been fascinated with what it means to be human, there’s been a pretty stark disinterest in the physical logistics of it – i.e. the fact that each and every one of our existences depends upon a delicate balance of chemicals and fluids within a bony tissue sack. All these space voyage films ask: what is humanity? Only High Life gives the obvious answer: a body.

Consider, for instance, the memorable HAL 9000 sequence around 2001’s midpoint includes a scene in which the rogue computer in charge of the ship jettisons the cryogenically frozen human crew members into space. It’s a cold, almost silent moment, the crewmembers’ (presumably dying) bodies nearly unrecognizable as human against the uncaring backdrop of the cosmos as they exit the ship. High Life has a similar scene near its beginning, wherein Robert Pattinson’s character drags the bodies of his crewmates to an airlock and then ejects them one by one into space, but the difference between this scene and the parallel one in 2001 is telling. Pattinson struggles and sweats as he carries each body toward eternity; each human he disposes of has weight and physicality. 2001 communicates the abstract idea of a life ending. High Life stresses to an excruciating degree the physical mass and shape that life occupies.

It’s not just this one scene. The emphasis on the biological weight of humanity permeates High Life, especially in those moments that echo previous space voyage films. In a goopy subversion of Interstellar’s “through the singularity” moment, Mia Goth’s character pilots a ship into the black hole, and her body is pulled stretched and pulled apart until nothing is visible but just bloody viscera on her helmet’s visor (a process that, I kid you not, is officially known as “spaghettification” among astrophysicists); perverse echoes of both 2001’s zero-gravity toilet and Solaris’s reality-bending planet can be heard in High Life’s “fuckbox,” a device on the spaceship that seems to be some sort of virtual-reality sex machine – the reduction of one of humanity’s most intimate habits to merely the regulation of bodily fluids. Elsewhere in the film, viewers are “treated” to shots of semen, menstrual blood, and good ol’ regular blood, to say nothing of the plot, which, as mentioned earlier, in part revolves around the harvesting of sperm in order to create new human life (implying that all human life requires is just putting the right chemicals in the right places). High Life does not want its viewers to escape this point: we humans are nothing but tissue and juice.

There’s an innate horror in seeing the human experience rendered as merely the sum of its biological processes, and a lot of High Life’s power comes from the way our minds desperately reject that strictly materialist paradigm. Despite the fact that it is quite literally the definition of natural, the idea that nothing of humanity exists except that which can be scientifically measured has an unnatural ring to it that our meaning-hungry brains have trouble accepting. Accordingly, High Life is not just a movie about what humanity is but also about what humanity does, and what humanity does best, at least in the eyes of this movie, is to impose meaning on top of that biological framework.

In an objective way, human life may in fact be meaningless except so much as it adds up to the exchange and redistribution of biological compounds, but dammit, human beings are going to create existential significance out of that biology, by hook or by crook, and with that significance meaning and value. It’s something we viewers do instinctively; we see a character die, and we value that as either good (if the character is a villain) or bad (if the character is a hero), despite the fact that on a purely natural level, all that has happened is a re-ordering of the tissues and compounds that made up that human’s body. The only way we recognize this event as being good or bad at all is if we create some sort of framework for the loss of human life that tells us what that loss of life means, and that framework isn’t an inherent feature of the natural world; it’s an overlay created by and visible only to us humans.

Part of what’s so fascinating about High Life is that the movie shows this process in real time. The voyage in the film is a scientific one and therefore should be free of meaning – science ostensibly being an “objective” endeavor premised on observation and data collection. And yet time and time again, the film shows its human characters projecting significance onto their scientific mission. There is the grief the characters experience when each gestating child dies; there is Robert Pattinson’s abstinent refusal to donate his sperm in protest of the mission; there is the assaultive scheming of Juliette Binoche’s character, who is the mad scientist put in charge of the mission. Pattinson’s character is called a “monk”; Binoche’s character is referred to as “the shaman of sperm.” None of this makes sense without the assumption that these human beings are perceiving one another not just as meat sacks but also as actors within a meaningful schema they have developed – a schema that helps them impose value judgements and ascribe significant to what would otherwise be just another biological ecosystem. That’s to say nothing of the fact that all of the characters in High Life are prisoners, people whose society has (de)valued based on a moral framework imposed on the natural world; the entire mission, so scientific and supposedly objective, has been built upon yet another overlay of meaning.

One of the first words uttered out loud in High Life is “taboo,” which Robert Pattinson’s character says to his infant daughter, and what is a taboo but an instruction for human behavior based on the way that another human has overlaid meaning on the natural world? In fact, the whole collection of scenes involving the infant daughter is the film’s meaning-making idea in microcosm. The baby observes Pattinson pounding an air conditioning unit, so she then pounds the air conditioning unit, assuming it is a “good” thing to do; the baby watches the flickering images from Earth projected on a screen, images which include those of people praying, and so later, when the movie has moved into her adolescence, she mimics the prayerful posture of the people she’s seen on the screen, assuming that this is part of the world’s framework of meaning. What Pattinson’s character describes as taboos (not eating one’s own excrement, for example) are key to survival, so when his daughter begins adding to his framework, it conflates those new additions, too, with survival. Being human, the overlaying of meaning onto biology is inescapable, because that overlay is intrinsic to conscious survival. Simply to continue existing is to create meaning.

In his famous essay “The Myth of Sisyphus,” the existential philosopher Albert Camus compares the human experience to that of Sisyphus, the character from Greek mythology who is condemned to repeat the same task forever: push a boulder up a mountain, only to have it roll back to the bottom again as soon as it reaches the peak. According to Camus, this task is, like the human experience, absurd: a meaningless, repetitive work without intrinsic value. The boulder will roll down the hill no matter how Sisyphus pushes it upward; we humans struggle at the same mundane tasks day in and day out, no matter what, until we die. The goal of life then, Camus says, is to impose meaning on the absurd struggles of day-to-day existence – an imposition Camus calls a “revolt” against the inherent absurdity of the world. Claire Denis seems to have a similar idea in mind with the crew in High Life, condemned to the rote absurdity of a scientific study, only her particularly visceral iteration of this philosophy seems less grounded in Sisyphus than it is in another eternally punished Greek figure: Prometheus, who is chained to a rock and must suffer each day as an eagle feeds on his liver, which then regrows overnight for the eagle to devour again the next day. Denis’s characters – and, as the movie suggests, humans writ large – are themselves in a sort of “Myth of Prometheus,” imprisoned in an experience that day after day forces them to suffer through the absurd (and sometimes excruciating) regulations of biology. To survive such an experience is to create taboos and anti-masturbation monks and shamans of sperm – a revolt against the senseless ebbs of hormones and humors.

But (and this is the crucial part) the movie doesn’t regard all forms of revolt equally. All human life is confronted with the same essentially absurd biological experience, but not all human life overlays the same values onto that biology. Juliette Binoche’s character, for example, so values the process of the crew’s scientific mission and specifically the objective of reproduction that she builds up a framework of meaning that (to her) justifies the rapes of both Pattinson’s character and Mia Goth’s character in the interest of creating life. Ewan Mitchell’s character creates an overlay that so values power and sexual gratification that he attempts to rape Mia Goth’s character. Pattinson’s character, on the other hand, builds a framework premised on protection, acting as a sort of guard for the crew against both the ritual abuse of Binoche’s character and the erratic fury of Mitchell’s, and then, when he is the only one left, as a protector of his daughter.

Camus argues that in an absurd world (i.e. the one we live in) there are no true authorities by which to ground rules; therefore, ethical standards are irrelevant in the formation of meaning, given that ethics are grounded in some sort of authority (even if just an abstract one like “reason”). For Camus, the human experience is an isolated one in which each overlay of meaning is a world unto itself. This seems to be Denis’s major departure from Camus’s ideas. The fact that humanity is biology does nothing to free the viewer from a valued response to the characters’ actions, nor does it seem to liberate the camera from this subjectivity either. The panicked, horrified way with which the cinematic style regards the actions of Binoche and Mitchell, a shocked and quivering camera shaken by a dissonant score, seems to indicate that the meanings they impose over their biology are ones to avoid. Plus, as the movie’s opening minutes show, they are dead-ends, all terminating in the same haunting space burial, pieces of biology stripped of meaning, floating in the infinite darkness of space. Of course, Camus would argue that all life shares this dead-end. But in the film’s final minutes, Denis shockingly, subversively seems to disagree.

At the movie’s end, Pattinson’s character and his daughter decide to fly their ship into a black hole together. Despite the fact that this very same action resulted in the gruesome spaghettification of Mia Goth’s character, the characters’ body language indicate that this decision is a tender one made mutually; it in fact feels like the culmination of the relationship between the man and his now-teenaged daughter, which, over the course of the movie, develops from its initial basis on Pattinson’s protection into a much richer, more collaborative experience. Unlike any other characters in the movie, these two have managed to create a relationship based on their care for one another: on a shared framework centered on the collective preservation of human life – in other words, a community. Whereas the rest of the characters toiled in their own isolated paradigms of meaning, these two have created a construct in which they can both exist and respect each other. It is, as all communities are, a social construct irrespective of any sort of any objective or biological truth, but it’s only through collective constructs that any ethics can exist at all. If enough individuals adopt a framework that values other human life, then an ethical paradigm is born, and humanity’s quest for meaning escapes the dead-end of the grave because the collective ethics transcend any one biological life. The care for others (dare I say it – love) supersedes death.

Haters may hate, but Interstellar said it best: “Love transcends time and space.”

Like Interstellar, High Life literalizes this idea. Alone, the black hole destroyed Mia Goth’s character, but as a collective, the father and daughter are able to pass through not just unscathed but reborn: on the other side of the black hole, their spaceship and spacesuits have disappeared along with the entirety of the physical world. These protective devices are, of course, what has preserved their biological life, so with them gone, the two have effectively transcended the fight for survival and therefore their biology as a whole. Are they actually inside the black hole? Have they died and entered the afterlife? Is this a final projection of meaning onto the natural world by their dying brains? Is it somehow a tangible reality created from that meaning-projection? The movie is unclear on its answers to all these questions, but one thing is for sure: whatever it is that has happened to them, when the father takes the daughter’s hand and the two move together forward into the light, it matters.

If this is indeed existentialism by way of the myth of Prometheus, this final communal transcendence makes sense, since Prometheus’s story ends not (like Sisyphus’s) in eternal absurd repetition, but when Hercules arrives, shatters Prometheus’s chains, and takes his hand. To quote another existentialist, hell may be other people. But Claire Denis somewhat provocatively insists that heaven is others as well.

Discussed on the podcast here: