Festival Coverage by Andrew Swafford

For eleven years running, the Knoxville Horror Film Fest has consistently shared a diverse array of horror films: new indies and old favorites, short films both local and international, atmospheric mood pieces and splatter-heavy exploitation pictures. This year was no exception, and actually offered a stronger selection than last year’s 10th anniversary extravaganza. Over the course of five days, I was able to catch four regional premieres, four remastered cult classics, and a whole lot of shorts – including one I helped get made!

Häxan

Knoxferatu IV: Silent Shorts and Häxan (1922) by Benjamin Christensen

The horror fest self-describes as a four-day event, but I really think of it as five. Over the past few years, it has become increasingly difficult to separate the festival proper from Knoxferatu, an annual celebration of silent horror cinema hosted by Kelly Robinson that takes place the night before and is, for me, a consistent highlight of the whole experience. The event is always headlined by a canonical feature (always presented with a live score) following a selection of related short films curated by Robinson, an expert on rare and lost films. Robinson’s short film selection has been instrumental in my own education on early silent cinema, and the features are always a treat to see come alive on the big screen with live music. The first year culminated in the event’s namesake, Nosferatu, and subsequent years honored The Phantom of the Opera and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. I was thrilled to learn that this year’s feature was Häxan, a pioneering Swedish documentary about witchcraft and superstition that we covered on the Cinematary podcast several years back.

Häxan is a strange beast: it clocks in at just 105 minutes, is split into six unique sections, often feels overlong and draggy, but is wholly worthwhile as an odyssey through occult lore and the documentary form. (As Kelly Robinson said in her intro: “if you’re ever bored, just keep watching: it’ll change!) The film opens as a collegiate history lecture, complete with cited sources, crude PowerPoint-style slides, and a pointing stick coming in from off screen to emphasize certain details. Later, it becomes a series of century-spanning dramatic reenactments of historical witch trials, and then phantasmagorical visualizations of walpurgisnacht (the witches sabbath), bringing into fleshy reality the fabricated stories of the accused. The reenactments that are more grounded in reality are the worst offenders when it comes to making the film drag, but the Satanic ritual sections are something to behold, with grotesque costume design, haunting silhouette work, deep color tinting, and overwhelmingly busy visual compositions. Those who have already seen Häxan are advised to watch it again in the new restoration (available now on Criterion Bluray) to take in all the intricate detail of these set pieces.

In the film’s final two sections, Häxan becomes both more metafictional and more present. Christensen doesn’t shy away from making reference to himself as a filmmaker and his actors as actors, breaking the reality they have constructed to note how they have been affected by the information conveyed by the documentary – one such moment being an actress electing to subject herself to one of the many torture devices catalogued by the film. Christensen also squares his timeline with his present day, connecting the way supposed witches were treated throughout history by the church to the way contemporary “hysterical” women (often the same types of women: those seen as too young/sexual or too old/delusional) were being treated by the mental health system. For all the ways Christensen puts himself in the film, he’s oddly aloof with how he seems to feel about so-called “hysteria,” which modern viewers will understand got untold numbers of innocent women locked up and lobotomized under the banner of scientific medical practice in the early 20th century. Is Christensen suggesting that the existence of hysteria finally proves the existence of Satanic forces at work in the world, or does he think that the diagnosis is just a newly mutated way of controlling socially outcast women? Regardless, the subject matter of the film is grim, tough, and absolutely overstuffed with nightmare imagery.

Those Awful Hats (1909)

Princess Nicotine (1909)

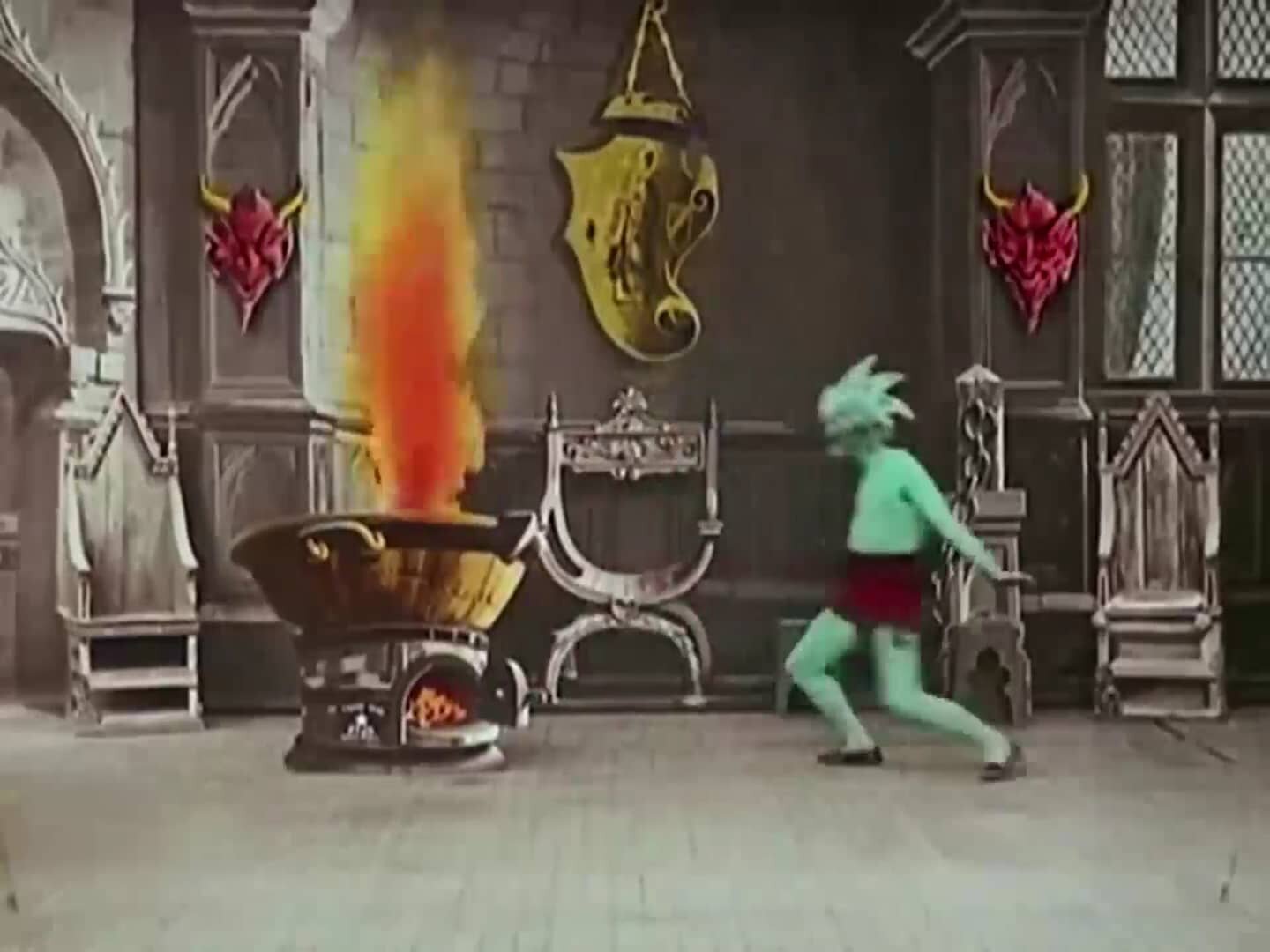

The Infernal Cauldron (1903)

As far as the shorts that played before Häxan go, there were three major standouts: (1) Those Awful Hats, a playful D.W. Griffith PSA about why women shouldn’t wear obstructive headwear to the theater (or else they’ll be picked up by a crane and thrown into the movie itself, I guess?) (2) Princess Nicotine, an exercise in visual effects work that visualizes a man being visited by a cigarette fairy – who was actually projected into the camera via a set of mirrors, not double-exposure or any other sort of composite image! And (3) The Infernal Cauldron, which is one of those George Méliès shorts where the director plays a devil and terrorizes his cast with sleight-of-hand trickery in hand-painted pastel color. All are available online via the links above, but watching these in a theater as pre-roll for Häxan was a real treat.

The Manitou

Girdler-Thon: The Manitou (1978) and Grizzly (1976) by William Girdler

This year’s Knox Horror Fest officially officially kicked off with what the programmers called Girdler-Thon – a triple feature honoring the prolific yet short-lived career of William Girdler, who is beloved by certain genre buffs who delight in trashy B-pictures. I will readily admit that I am not this kind of horror fan (nor had I even heard of Girdler before this year’s fest, which perhaps invalidates any credibility I might hope to possess), and my general disinterest in VHS-ready sleaze and splatter does leave me feeling a bit locked out of the fun people have every year when these titles inevitably come up. Regardless, the William Girdler films making up “Girdler-Thon” were The Manitou, Grizzly, and an undisclosed third title, later revealed to be a film with such dubious distribution rights, that the festival couldn’t advertize showing it. As a person whose day job requires me to wake up very early in the morning, I couldn’t stay for the undisclosed third screening – but I wouldn’t have been able to write about it if I did, nor will I drop the title here out of respect for the Knox Horror programmers who really stuck their neck out to acquire that film. Needless to say, that would have been the event of the night – I was instead left to reckon with The Manitou and Grizzly, two exploitation films of varying quality that I can’t say really sold me on Girlder’s genius.

The first film – The Manitou – seemed to drum up more excitement than the second simply due to its absurd premise: an ancient Native American shaman is reborn as a fetus growing inside a white woman’s tumor. The protagonist of the film is neither the woman nor the shaman (who is identified as a “manitou”), but rather a sham psychic played by Tony Curtis, of all people? The early goings of his performance are, admittedly, downright hilarious – watching an old Hollywood superstar make up tarot readings and daily prayers for gullible old ladies while dressed in wizard robes and listening to new age music, only to switch the hi-fi to funk and begin dancing around his apartment as soon as they walk out the door, is an absolute treat. Unfortunately, the movie must soon turn into a medical intrigue / possession film about this woman’s shaman-tumor, which, as amusing as it sounds on paper, is clunky and uninteresting in practice. The shaman himself, once he shows himself, has no presence and is obviously artificial (though I suppose this is part of the appeal for a lot of audience members), and the journey to discover things about him before he unveils himself is just a slow, unfunny doling out of information. To use terminology from Carol Clover’s seminal text Men Women and Chainsaws, The Manitou is a classic “white science vs. black magic” film, like most possession pictures. The protagonist and his allies are white men who believe in science and western definitions of “objective reality,” but this cold, logical mindset is increasingly refuted by the supernatural presence at the film’s center (often possessing the body/spirit of a mostly passive female character, who serves as a more “open” vessel) and sages who bring hiterto disregarded knowledge into light, here represented by Michael Ansara’s character “John Singing Rock.” White Science vs. Black Magic films can be powerful refutations of Eurocentric, secular ways of viewing the world – I Walked With a Zombie is my personal favorite, due to its nuanced, respectful handling of Haitian voodoo – but they can also be exotifying and othering of whatever culture they’re depicting, which The Manitou is definitely guilty of, if one is willing to take it seriously enough to consider this dynamic. By the end, the film is definitely uninterested in being taken seriously, however, as it closes with an out-of-nowhere, gonzo space opera sequence that makes the entire film worth watching, warts and all.

The second (and, for me, final) film of Girdler-thon was Grizzly, a shameless rip-off of the Jaws formula. You can feel Girdler ticking each individual box as he presents the woodsman-equivalent of every single plot beat, character type, and set piece from Spielberg’s original film: the POV monster shots, the determined ranger dealing with domestic unease, the park executive who refuses to close down even as the danger ramps up, and the bombastic pyromania of the beast’s eventual demise. Like Gus Van Sant’s shot-for-shot remake of Psycho, some audience members might be deeply fascinated by the prospect of watching a classic film be reduced to pantomime, but for me, sitting through it was a hollow, draining experience. Grizzly is hardly the only Jaws ripoff, with animal survival movies becoming their own little subgenre in the decades since its release – just the past few years have given us two great examples in The Shallows and Crawl. These two titles, for me, well illustrate the two ways to do a Jaws movie right: (1) you can realize, to borrow Mark Kermode’s oft-repeated phrase, that “Jaws isn’t really about a shark” and use the animal attack narrative as a frame for genuine character development, as is the case in Spielberg’s film and, to a certain extent, The Shallows, or (2) you can double-down on cheap thrills and give the movie a sense of non-stop urgency, as in Crawl. Grizzly doesn’t really do either of these things. During the scenes depicting violent kills, the bear is hidden and shot around so obviously that there’s no way to actually feel involved in it, and in the scenes depicting human drama, the people are such obvious cookie-cutter ciphers that there’s no way to actually feel compelled by them. The whole thing is just kind of there, up on the screen, fulfilling very little purpose other than letting me enjoy some pleasant enough photography of America’s majestic National Parks.

Blood Machines (2019) by Raphaël Hernandez, Savitri Joly-Gonfard, and Carpenter Brut

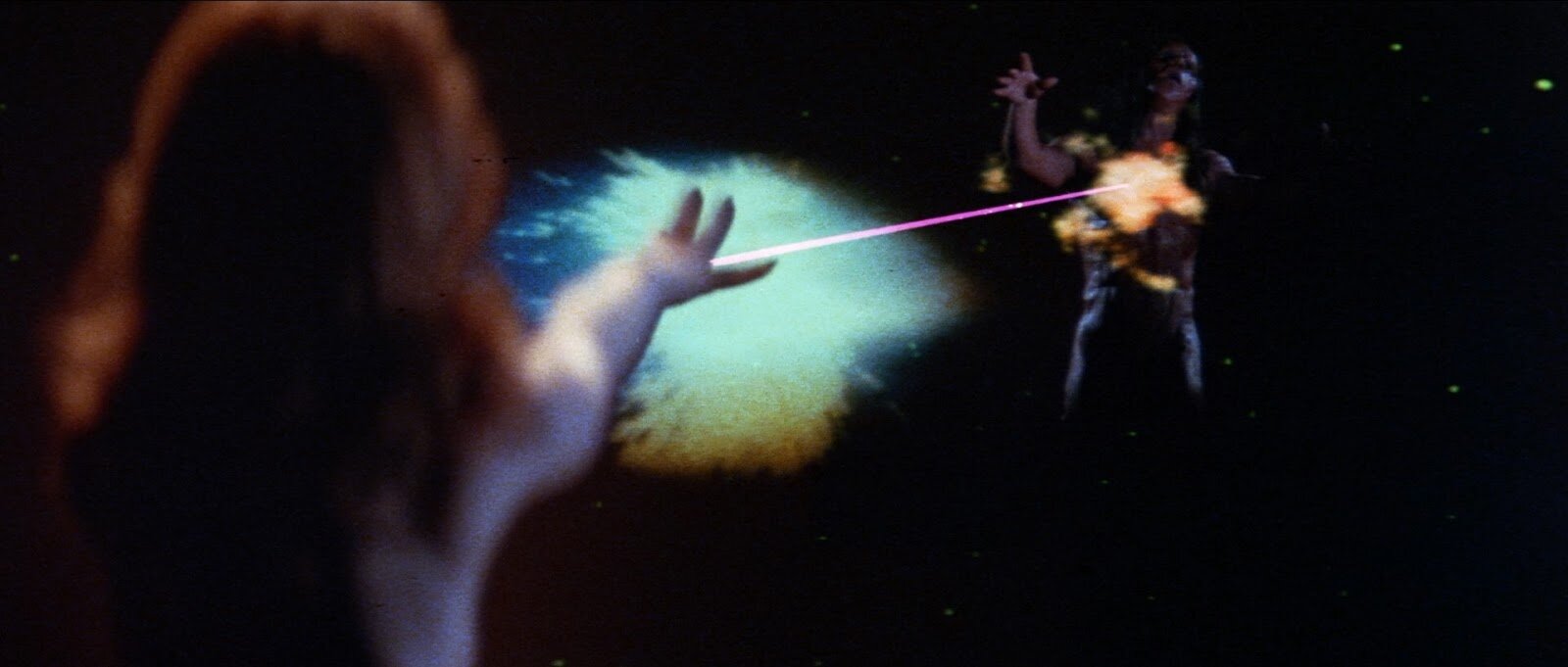

Synthwave artist Carpenter Brut isn’t one of Blood Machines’s two directors (who are sometimes referred to collectively as Seth Ickerman), but he earns author status by way of his music being the driving force of this film, which was described by the fest’s lead programmer as an hour-long Carpenter Brut music video. His music is characterized by driving, pulsating, straightforward synth arpeggios, looped and stacked atop of one another until they culminate in grand, wicked crescendos. In Blood Machines, that musical aesthetic is complimented with neon-drenched psychedelic sci-fi imagery and a questionable story about...space pirates? And artificial intelligence? Or something?

To the best of my understanding/memory, the story here involves a spaceship helmed by two men and their Cortana-esque female AI mainframe landing on a desert planet only to be held captive by a group of pirate women, who eventually kill the men and liberate their AI. Throughout this story of female empowerment, however, there is great attention paid to these highly aestheticized figures of nude women (seen above) with glowing upside down crosses extending out of their pubic area and across their abdomens. Sometimes these women are androids, and sometimes they’re spaceships, but they’re always worshipped by the camera as fetish objects, which greatly undercuts any sort of gestures the narrative might make towards “female empowerment.” The women at the center of the film may be killing men and liberating cyborg women, but the male creators of that story are loving that, if you know what I mean. The film is perhaps too light on story or logic to even take these sorts of representational concerns seriously (as with The Manitou), but part of me worries that hand-waving this stuff away when it’s just fodder for “cool imagery” is just reinforcing the unconscious and automatic way in which women are so often reduced to fetish objects in sci-fi cinema and edgy music iconography.

But the film is not lacking for “cool imagery” otherwise! The most striking thing about Blood Machines is the film’s maximalist use of CGI, which has become a crutch for most Disney-owned Hollywood blockbusters that ends up making them look weightless and rubbery. Blood Machines similarly places its few live actors in completely digital environments, but the film is a testament to the fact that CGI can be deployed in much stranger and more ambitious ways than it regularly is. All the imagery here gleams and moves like it’s part of a singular bizarre, digital organism – one whose heart beats to the rhythm of a Carpenter Brut bassline.

Tammy and the T-Rex: Gore Cut (1994) by Stewart Raffill

Another example of the Knox Horror Fest digging up old VHS-era oddities, Tammy and the T-Rex is one of those magnificent bad movies, directed by the filmmaker behind the notorious corporate tie-in Mac and Me and full of moments reminiscent of Nic Cage shouting the entire alphabet in Vampire’s Kiss. The plot follows Denise Richards and a very young Paul Walker as high school sweethearts sabotaged by Richards’s greaser ex-boyfriend, who straight up murders Paul Walker (by leaving him in a zoo full of carnivorous animals??). One thing leads to another, and Paul Walker’s brain is transplanted into an animatronic Tyrannosaurus Rex who must then prove his continued existence to his bereaved girlfriend. The whole thing has the feel of a particularly strange Disney Channel Original Movie, but there’s a lot of previously censored blood and guts involved in all this body-swapping (and subsequent dino carnage), which this recently reconstructed “Gore Cut” of the film has now restored. However, I’m baffled as to how any possible cut of this film could be considered studio-approved, let alone family friendly. There is quite a bit of on-screen and off-screen sex, including one implied sequence that presaged the advent of dinosaur erotica (not linking this).

As strange as the film is, it is surprisingly cine-literate (and just literature literate) in the way it taps into the various precedents that paved the way for a story like this. On one level, it is an obvious riff on Jurassic Park (released just one year prior) and it’s highly publicized innovations in special effects work – the “mad scientist” character responsible for Paul Walker’s animatronic T-Rex body even has some uncanny similarities to Steven Spielberg. But he is also an archetypal mad scientist like Mary Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein, which has more than a few things in common with Spielberg’s science-and-capitalism-run-amok monster movie. On another level entirely, the film evokes King Kong on more than one occasion, what with its “pretty blonde girl being carried away by giant monster while on the run from the police” and all. In a way, it de-problematizes the King Kong dynamic by making the relationship at its center a pre-established one that is both consensual and pure-hearted. (The romance is acted with great sincerity, too – Denise Richards really loves that T-Rex!!) And perhaps in response to King Kong’s anti-black racial coding, one of the most empathetic central characters here is both black and queer, only mocked by obvious bigots and actually spared from the carnage by Paul Walker’s T-Rex in one of the film’s best moments.

The single greatest moment of the film, however, comes at the very end – and I’ll avoid spoiling it here in hopes that you don’t need any more convincing. Without just giving a laundry list of its many hysterical details, what else is there to say about Tammy and the T-Rex? It’s strange and delightful and absolutely worth watching when the Gore Cut is finally released on blu-ray by Vinegar Syndrome this Black Friday, but I’m especially grateful for the opportunity to experience it with an audience, which was easily one of the most fun screenings of the festival.

Kindred Spirits (2019) by Lucky McKee

Lacking a single protagonist, Kindred Spirits shifts its focus continually among a complex constellation of related women at different places in their lives: Chloe (Thora Birch of Ghost World fame) is a middle-aged single mother who had her now-teenage daughter, Nicole (Sasha Frolova), while still extremely young, and is therefore very cautious and fearful concerning the girl’s adolescence; as a child, Nicole’s life was saved by her very young aunt Sadie (Caitlyn Stasey), who became estranged for many years but is now, out of the blue, back in her family’s orbit. “I owe you my life,” says a small Nicole, in the film’s only flashback. In several ways, she gets it, when Sadie returns to her sister’s home to relive her lost youth.

For a substantial amount of its runtime, Kindred Spirits is an uncanny thing: a film, written by a man and directed by another man, that plays as a sensitive ode to female friendships. As someone with limited firsthand experience, my instincts could be wrong on this, but Kindred Spirits seemed to somehow key into very specific cadences and familial dynamics that don’t exist between men – the strange types of sisterhood that develop between mothers and daughters, between sisterless girls and the slightly older women in their lives, and of course between actual sisters. Like any good character drama, it’s an actors’ film, in which intonation and facial tics buoy the audience’s attention; almost every scene is a dialogue scene, but one particularly vivid image has become subtly imprinted on my consciousness: Nicole and aunt Sadie, in Nicole’s room, just talking, while bathed in soft blue light from a rotating, prismatic lamp. This image seems to capture so much about these relationships: intimate, sublime, slightly unreal, and ever-shifting.

And shift they do: Kindred Spirits is a film of many twists, evoking Psycho and Persona as it spirals out into Shakespearean tragedy and feeling all the more painful due to the way the central relationships are so effectively romanticized in the film’s early stretches. On a thematic level, the unfolding catastrophe of Kindred Spirits warns about the fetishization of youth, presenting one heightened case study of youthfulness being pursued ruthlessly as well as a modest, mundane portrait of characters settling into middle age, with the latter coming across as something truly romantic. In no way the type of film one expects to see at horror festival, Kindred Spirits feels small, special, and singular. Its handling of nuanced and multifaceted character dynamics is enough to make you both swoon and shudder, and it features my favorite acting performance I’ve seen all year from Cailtlyn Stasey, who carries nearly every scene with these hairpin turns of affectation: teasing and playful at one moment, sincere and gravely serious at another, but always believable and real even in her darkest moments.

The Evil Dead (1981) by Sam Raimi

I watched Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead trilogy in exactly the wrong order: first seeing Army of Darkness and not getting it at all, then seeing Evil Dead 2 and enjoying the cartoonish energy of it without understanding the references, and only just now seeing The Evil Dead and being able to appreciate the brilliance of the whole series for what it is, each entry growing exponentially more ludicrous and self-referential. But despite the fact that Raimi (not to mention other filmmakers) would later mine his foundational “cabin in the woods” flick for humor, the OG has plenty of unhinged silliness all its own – there’s even a ragtime number!

Plenty of folks have probably written about it more effectively than I have, but Raimi’s camerawork is incredibly inventive: the perspective careens this way and that, implying a sense of malevolent sentience the viewer is cursed to look through the eyes of. As the violence of the plot escalates, so too do the practical effects, which after a certain point just feel like they’re just spewing blood, dirt, and leaves onto the audience in gleeful obliviousness to the film’s repetitive structure. The backwoods of Tennessee is a perfect setting for a movie this gritty and homemade, but I’m glad I hadn’t seen it when I would play in the same woods, young enough for things like this to give me nightmares.

On the other hand, it’s precious to see a young Bruce Campbell not yet grown into his swagger: one excellent scene involves him standing stiff in the corner of a room, clutching a hatchet to his chest in fear as one of his last remaining friends attempts to dispose of a ghoul. Not yet the groovy, madcap Schwarzenegger-type he would become in Evil Dead 2 nor the time-traveling American gladiator he would embody in Army of Darkness, here he’s often not even Ash – he’s “Ashley,” some innocent dope played by Sam Raimi’s high school buddy.

Girl on the Third Floor (2019) by Travis Stevens

One of the biggest surprises of the festival was Girl on the Third Floor, which starts as an HGTV-style home renovation simulator before peeling back the drywall to reveal a particularly grotesque piece of psychological horror. The film’s protagonist is Don, a muscle-bound, tatted-up husband and father-to-be played by Phillip Jack Brooks in a performance that carries the entire film, with a presence and swagger reminiscent of both John Cena and Mad Men-era Jon Hamm. Don and his pregnant wife have recently purchased a huge, historic fixer-upper out in the suburbs, and he has moved in a few weeks early to clear it out, do some painting, and get the house in shape for the family. The first thing worth noticing here is how patiently and thrillingly director Travis Stevens frames Don’s manual labor: a great deal of time is devoted to the process of cutting raw material, ripping out and replacing imperfections, excavating hidden recesses within walls, discovering things about the house’s structure that weren’t obvious at first glance.

And it’s in that exploratory construction work that the house reveals its allegorical weight, as Don comes across sockets that ooze bodily fluids and walls that hide pockets of bile. In fixing up the house, he is attempting to reform himself into a family man, but it’s soon clear that his domestic commitment is underscored by vices and lies: so the house makes these transgressions into fleshy, Cronebergian substance, even offering him new temptations to lead him even further astray. In much the same way as James Wan’s Conjuring franchise, Girl on the Third Floor is a roundabout faith-based film, as direct redemption is offered to Don by way of the church across the street, pastored by a middle-aged woman whose occupation challenges not only Don’s sinful nature, but his assumptions about women as well. As a well-crafted allegory about men who resist settling into domestic life, Girl on the Third Floor lays a strong foundation for the horror it eventually reveals.

The horrific imagery awaiting viewers in Girl on the Third Floor’s final act is a bit of a mixed bag, however: on the one hand, it absolutely terrified me in some moments and made me deeply squeamish in how far it goes with its shocking body horror effects work (“properly nasty,” as Mark Kermode would say); on the other hand, it does tip over into downright silliness after a certain point, and perhaps goes too far in attempting to visualize a backstory that would have been better left implied. Regardless, I admired what this film set out to achieve and was really impressed by the extent to which it succeeded. Girl on the Third Floor is definitely one for indie horror fans to check out by the end of the year – and it’s actually already available on VOD!

Bliss (2019) by Joe Begos

Joe Begos had two films premiere back-to-back at this year’s horror fest – Bliss and VFW – and took home the “best director” prize at the awards ceremony. I only had time to see one and opted for Bliss, a drugged out vampire movie about hipster artists that draws obvious parallels to Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction. But where Ferrara’s film is black-and-white, draining the indulgence of drugs-by-way-of-vampirism of any sensual pleasure, the aptly-titled Bliss leans hard in the other direction, sweeping the audience up in the psychedelic frenzy of going on a bender, having wildly uninhibited sex, getting lost in one’s own creative process, and blacking out at the height of it all only to wake up facing confusion and withdrawl. Bliss effectively transports its audience into this feverish headspace primarily through lighting and editing, both working together to create deep-red-and-blue neon strobe effects that reach dizzying heights.

As drug movies often go, however, the arc of the film is a repetitive one, as we see our central starving-artist-turned-bloodthirsty-vampire take this ride and its inevitable crash again and again and again, making minor progress on her artwork while increasingly alienating all her reliable friends in the process. As is the case in Abel Ferrara’s film, it makes sense that a portrait of addiction should ultimately be a draining, discouraging experience (this felt very long to me, even at just 80 minutes!), but I can’t help feeling that the ideas being conveyed here are basic at best and conservative at worst: there’s something hateful about the way it depicts aimless Californian bohemians, shriking off responsibility to indulge their own base impulses, ultimately leeching off of the responsible capitalists all around them in a horrific, vampiric way. But tackling the very real problem of addiction in artsy circles is a tricky tightrope to walk without reinforcing certain reactionary viewpoints, so it’s possible that I’m reading too much into this and Bliss means to come from a place of empathy. Still, though, it also doesn’t seem to be saying anything more substantial than “drugs bad,” which makes me feel a little less generous when thinking back on the exhausting process of watching this character’s repetitive spiral into oblivion. The raw filmmaking talent on display in those early tripping sequences is undeniable, though.

Depraved (2019) by Larry Fessenden

The Frankenstein story has been retold countless times, and Depraved is a unique adaptation from undersung indie godfather Larry Fessenden, who had worked as a producer and actor in films as diverse as House of the Devil, Broken Flowers, and (my favorite) Wendy and Lucy. His twist on the story is threefold: (1) we are introduced to the young man whose brain in harvested for Frankenstein’s monster in the opening scene, establishing empathy for the life and romance he has lost when his consciousness is unwillingly stolen and tampered with; (2) Frankenstein himself is an Iraq-war-medic suffering from PTSD and motivated by the desire to save lives in a way he wasn’t able to on the battlefield; (3) this operation all takes place under the shadow of big pharma, whose money is being unknowingly funneled into the passion project of the Frankenstein character (allegorically presented as a Yahweh-esque figure who creates an Eden for his Adam to develop within) and his much more mercenary business partner (presented as a serpent-like trickster who lures the monster – literally named Adam – to cross lines and mistrust his maker). What does this ultimately add up to?

I have no idea. Larry Fessenden is taking a lot of creative liberties here – and even gets pretty visually ambitious in the way he represents synapses firing in Adam’s brain overlaid atop his day-to-day learning experiences – but I was left completely cold by what this is all meant to mean. In expanding the reach of Mary Shelley’s original narrative so much (stretching its fingers into the institutions of big pharma and the military industrial complex, plus broadening the religious allegory already present in Shelley’s text), Depraved ultimately seems to come just short of any thematic conclusions. Perhaps the ambition to adapt the Frankenstein story itself is an archetypal folly of mankind, a tempting prospect that ultimately is better left in the hands of its original creator.

At the very least, the runtime is a bit too ambitious: almost two hours of this vaguely pointed plottiness becomes very tedious once the ending is in sight.

SHORTS TO WATCH OUT FOR

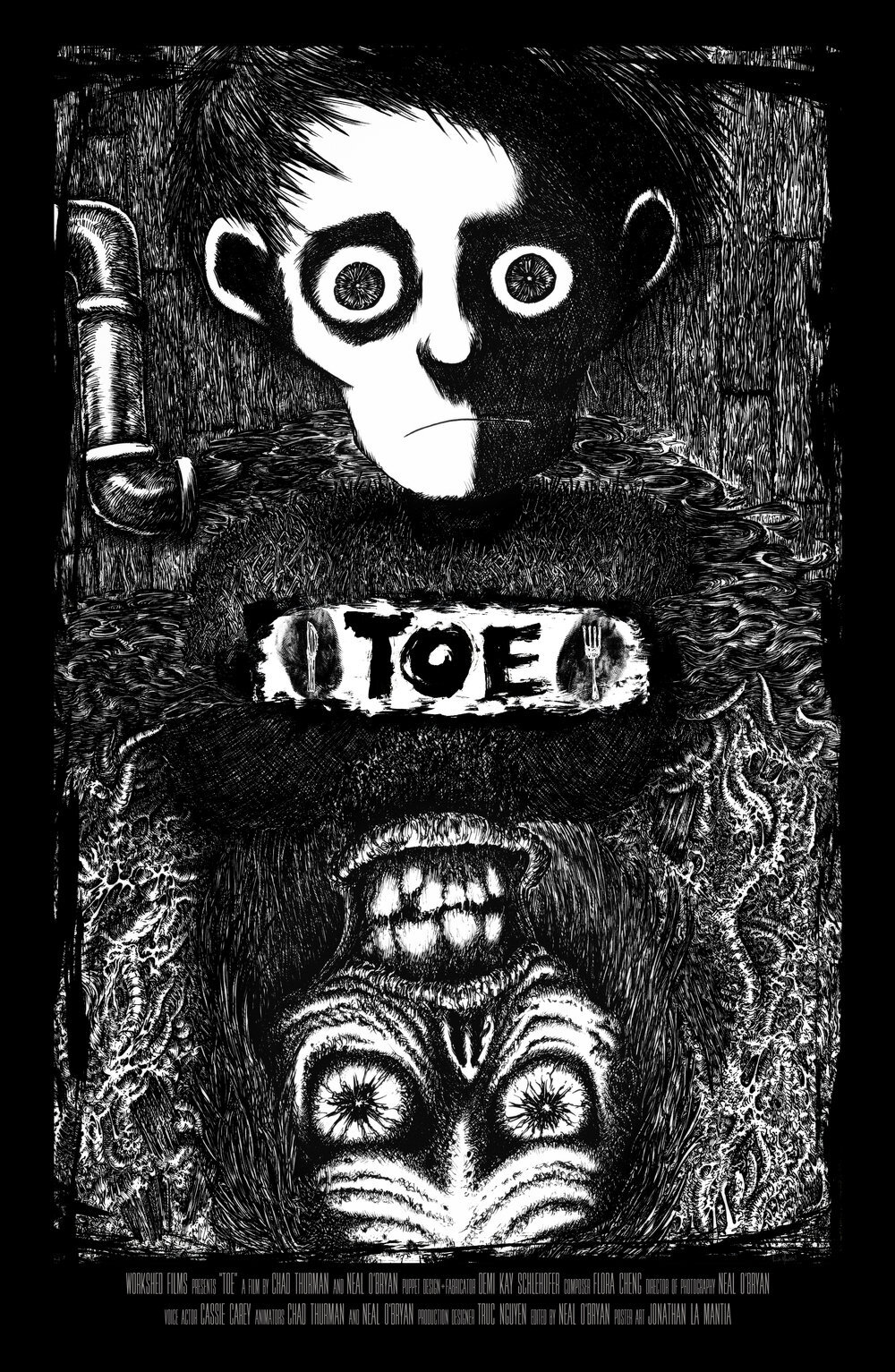

Toe - A very brief stop-motion animated film about a young boy being hounded by the undead. Reminiscent of Tim Burton’s best animated work (as well as Paranorman) if it was given the expressionistic, silent treatment of something like Eraserhead.

Noctámbulos (Night Owls) - An abduction film centering on an adolescent skater girl that reminded me of both this year’s Tigers Are Not Afraid as well as Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night. This features clean, confident cinematography and a great twist at the end.

Kissed - An intimate yet horrifying two-hander between a female cadaver and her philandering mortician, the already-great concept behind Kissed is elevated by it’s restraint and it’s strong performances.

One Last Meal - Filmed on location in a beautifully rusted and historic prison, Jill "Sixx" Gevargizian captures a grotesque dilemma about a death row inmate who, for his last meal, demands a pound of his warden’s flesh. I’ll also take this opportunity to express my anticipation for Gevarvizian’s upcoming feature, The Stylist!

Gaslight - A bartender getting off work at a symbolically-named establishment waits for the bus under a single streetlight, only to be confronted by a diabolic drifter; their short interaction ends up being an odyssey even given its short length, thanks to the great directing chops of Louisa Weichmann.

ETA - Okay, I can’t pretend to be objective here: I helped make this film, which is by my good friend Deja Lytle. My contribution was a 15-minute ambient/electronic score, but I maintain that I would love this even if I had nothing to do with it. Deja’s film is a slow, psychedelic revenge thriller, shot in downtown Nashville and set in the nocturnal world of rideshare apps, pulling extreme amounts of suspense from the trust that passengers are asked to place in the hands of their practically anonymous drivers. The Nashville skyline is seen here almost entirely from behind the windows of a car, and it glitters and gleams like Wong Kar-wai shot it. Deja is incredibly talented filmmaker, and I’m so, so grateful to have been involved in this project; I hope others get to see it very soon, whether that be at another festival or streaming online.

BEST OF THE FEST

The crowning of Kindred Spirits is perhaps an obvious result for anyone who bothered to read through all this coverage, but I really was taken by its strange magic, endlessly charismatic performances, and twisted narrative arc. It is, as I said in the review proper, a small film, so I don’t imagine it will create an enormous sensation when it becomes widely available or anything, but I hope those who do see it love Kindred Spirits as much as I did.

Until next year!