Festival Coverage by Andrew Swafford and Dylan Moore

For ten days in October, the Nashville Film Festival screened over 100 feature films from around the world. Established in 1969 and celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, it is the longest running film festival in the state. Andrew and Dylan were able to catch six features and ten short films across several days of the festival. They were even able to catch one of Nash Film Fest’s trademark music documentaries this year...

Strange Negotiations (2019) by Brandon Vedder

Andrew: Although fitting Strange Negotiations into my schedule added quite a bit of drive-time into my festival experience, I felt like I had a duty to see this one for a variety of personal reasons. For one thing, this is a Kickstarter movie that I contributed to in 2017, but my history with its subject – ex-evangelical indie musician David Bazan – goes back much further. Although I had enjoyed Bazan’s work in the Christian-rock crossover group Pedro the Lion, watching an excommunicated Bazan play solo at Knoxville’s The Square Room back in 2010 was literally life changing: I was in a local Christian rock band at the time but was falling out of my faith, and I went with my bandmates to see the overtly Christian headlining act (mewithoutYou, who still rip) only to have my soul absolutely shaken by Bazan’s cover of “Hallelujah” complete with Leonard Cohen’s original verse: “You say I took the name in vain / Well, I don’t even know the name...” My friends’ somewhat hostile conversation about Bazan after the show led to a long, difficult conversation in which I revealed my lack of faith (we’re still cool, by the way – one of these guys ended up officiating my wedding), and Bazan has been a sort of distant sage in my life ever since. When Bazan took up the practice of playing house shows, I attended more than I can now count – and I even interviewed him for the now defunct site VolBlogs when I was getting my start writing media criticism. Lyrically, his albums are poetic treatises on the ways in which religion, politics, and family dynamics intersect, but they’re also rich in textures and tones thanks to Bazan’s love of synthesizers and ambitious sound mixing. At his shows, things get more personal, as he regularly asks his audiences “are there any questions at this point in the show?” and is happy to carry on long conversations between songs, always casually profound and funny at the same time. Obviously, I love him; It’s very possible that no single artist has had a greater impact on my life than David Bazan, so driving several hours seemed like a small price to pay to hear his reassuring yet ever-questioning voice for a few hours.

Driving so long before and after the film seems only apt, considering how much Strange Negotiations focuses on Bazan’s own life on the road. Since having to play house shows for most of his income, Bazan has spent the majority of each year driving across America and away from his family. Being gone for much of his kids’ upbringing is a subject of intense inner turmoil for Bazan, who goes on tour not only to support his family but also because he’s dedicated to what he calls “the work” of speaking truth through his music and engaging in conversation with his still-largely-Christian fanbase about how to improve contemporary Christian culture and, by extension, American life more broadly. If I had to guess, I’d say about 25% of this doc consists of either drone shots looking down at Bazan’s van from a birds-eye view or dashboard-cam interviews with Bazan while he’s driving from show to show – there’s also a great montage in which the editor scrubs through all this footage at warp speed, while Bazan talks about how if you picked a random moment from his life, odds are that he would be behind the wheel of a car, alone. From my perspective, I wish the film would have confined itself to the car a little more strictly and allowed the storytelling to be done verbally by the man himself – he’s such an articulate, humorous, and moving speaker – but I understand why, for the sake of the uninitiated, the film also elects to provide a more traditional biographical rundown of Bazan’s life and career via archival footage and on-screen text.

Dylan: Well to the point about craft, besides the passenger-view camera, I do think they tried to give an abstracted feel for the amount of time Bazan spends on the road: blurred, faded night and rain shots; those bird-eye-view drone shots that show his vehicle made tiny moving across the US interstate and highway system, all leading up to that warpspeed scrub that you alluded to. And it is a bit corny of a device, but I appreciated what amounts to daydream sequences where we see Bazan in a moment of pause at a gas pump or in his hotel room that lead to milky, hazy images of his daughter as a little kid playing, in moments of happiness. Given the family tension and awkward phone calls shown throughout the movie, these moments stood out to me in the context of a documentary. Though as you say, I feel like I would enjoy more moments of Bazan talking through that drive time, but it seems like the movie wants his music to speak for him.

Andrew: I’m curious: as someone who came into this film as a relative newcomer to Bazan’s work, how did Strange Negotiations play for you?

Dylan: I felt it showed a solid snapshot of Bazan’s struggle these past handful of years being a traveling musician with a family on the other side of the country, playing house shows, and trying to find a different means to connect with an audience, particularly after his crisis of faith and falling out with a community he felt so connected to growing up. At one point, he tells a story about being hammered at a Christian music festival and the organizers who found out about it afterwards were none too pleased, so it doesn’t seem like he was getting many gigs with that community immediately after. It did help, though, to have someone like you, who has followed Bazan’s life as a musician, to point me to two turning point albums in his solo career (Curse Your Branches and Blanco, both of which get featured heavily in the doc) that gave me more grounding to stand on before going into this. As someone who has tracked Bazan’s work so closely, how accurate does this documentary feel to you? Do you feel like it creates a clear and fair impression of Bazan, his work, and his life as you know it?

Andrew: Yeah, absolutely. The arc of Bazan’s career – from a slightly subversive evangelical musician, to a raging drunk, to a born-again agnostic, to a family man struggling to make ends meet – has been pretty well codified by countless journalistic portraits of the guy (not to mention all of his podcast appearances in which he tells the now-familiar story), and this adheres pretty closely to the understanding I already had of the man. And I’m glad it exists, because it does serve as a much more visceral entry point to his tumultuous life and career than any single article or podcast ever could. I wish I were more enthused about the craft of it – and I wish it provided more of an economic analysis on what it means to be a working musician these days – but it’s a really solid hagiographic doc (between Life Itself, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, and RBG, we’re getting a lot of those nowadays) that does a good job capturing the image of a man who really does embody a lot of saintly qualities: kindness, humility, hope, and skepticism.

A Hidden Life (2019) by Terrence Malick

Dylan: Since catching Tree of Life the same year it came out, I have kept Malick’s recent movies on the periphery, missing them in theaters while filling in his films from previous decades sparingly along the way. Though every time I do watch his post-Tree of Life work, after some distance from their critical discourse, I feel like there is always something in them to appreciate and enjoy: small moments of actors’ intimacy and expression, being overwhelmed by nature’s monuments and human architecture, and the spaces between these modes – but I still have yet to see Song to Song.

Andrew: That one is by far the weakest of the lot, but I do agree with you. I find Knight of Cups to be especially resonant.

Dylan: A Hidden Life was no different for me, really. Given the opportunity to see a Malick movie on a large theater screen, it was hard to pass up. Set right before and during World War 2, it follows the love story and marriage of two characters named Franz and Franziska in their isolated rural Austrian village until a plane flies overhead signaling a disturbance in their peaceful existence and the start of Nazi conscription. I wished this one landed for me completely. There’s still plenty for us to dig into here, but maybe like his other recent movies, I need some time away from it and to experience it again. You mentioned before we saw it this one has gotten a lot better reception than his more recent movies possibly because of its clearer story and spiritual struggle. How are you feeling/thinking about A Hidden Life after some distance?

Andrew: I’m probably the Cinematary crew’s most vocal Malick-defender (in retrospect, we act like Tree of Life is some untouchable masterpiece, but even before To the Wonder made the rounds, people had some pretty negative things to say about Tree of Life), so ever since I saw this in Nashville after missing it at TIFF (it was Zach’s favorite film of the fest!), people have been continually poking me for my take. And I haven’t given it, because it’s a tough reaction to sum up – I don’t really have a “take” per se, but moreso a scattered series of observations and questions.

To start with the positive: water is wet, and this is a Terrence Malick movie, so it looks beautiful. Malick has been called a classical romanticist along the lines of Wordsworth and Blake (my background is in literature, so this is not to mention all of the great iconic paintings of the period that I don’t have the historical knowledge to talk about with any certainty), and I think his way of shooting nature in this transcendent, Edenic way really elevates the story he’s telling here. German Fascism, in all its mechanization, brutalism, and bureaucracy, is about the furthest thing you can get from the serene pastures and sloping hills of rural Austria, and Malick’s camerawork is really playing up that divide and how the encroachment of the Nazis into this space is a type of Biblical fall from grace, with the arrival of the Nazi ideology first and foremost (as Zach focused on in his review) playing the trickster serpent role here.

How that ideology spreads is deeply indebted to modern technology, which is communicated in two shots that I absolutely love: the first one that struck me is a very early shot in which we see Franziska walking away from her farm to marvel at a German warplane flying overhead and casting a shadow across her quaint village. We never see the plane itself, but the shadow and the noise from the plane tells us everything we need to know about this new type of technology, which is in stark contrast to the wooden tools and carts designed by these people for the purpose of agriculture (focused on a lot throughout the film).

The second shot I want to talk about – or a series of related shots, really – made for what I found to be the most powerful imagery in the film. It’s dusk, and we see the mountainous basin of this township from high up above. The hills are covered in a blanket of blue-green darkness, but we see small glimmers of light coming from a small number of houses along the mountainside. The shot would be relatively insignificant if it weren’t for the sounds that accompany it, which are distant echoes of a speech from Adolf Hitler being listened to simultaneously on various radios (or maybe phonographs? Hitler’s speeches were also distributed via phonographs). The shot communicates two things: (1) these people are isolated, far away from what the Nazis are actually doing, so (2) tech-assisted communication is the only way this Fascist ideology is able to reach them. It’s hard to imagine the Nazis coming to power in the sweeping way they did in any other time period – they fed off of these technological advancements in order to systematize their violent ideology. I don’t think Malick is saying “technology bad” here or anything (again, he focuses on the technology developed by the farming community quite a bit), but he’s insightfully observing the ways in which communicative technology allows hateful rhetoric to spread in ways that it just couldn’t otherwise. It made me think a lot about how today’s neo-Nazis have weaponized social media algorithms to radicalize people. (And, of course, the inverse is true – these channels of communication allow for oppressed people who previously didn’t have a voice in mainstream discourse to air their grievances, but that’s a conversation for another time).

Like I alluded to earlier, I also have a lot of questions and borderline gripes about this movie, but do you have anything else to add regarding positives, Dylan?

Dylan: I agree about the technological point, and I’m with you: that scene faintly hearing Hitler’s speech through darkness of the village at night will stay with me. It is interesting then, too, that one of Franz's first turns of not being in sync with Nazi propaganda was earlier, while still in training, when they were showing the soon to be soldiers films at night and he was the only one not impressed or laughing at the destruction and zeal on screen. But right, I want to add to the wrinkle that undercuts the “technology bad” notion. The way Franziska tells the story of her and her husband first meeting is with a swooping tracking shot of Franz riding a motorcycle into town, positively intertwining this technology with their story together. And another that is full of surprising, mixed emotion is the bicycle and the postman that rides it. It seems like every time there is a shot of them in front of their house and the postman rides by there is an awful probability they will stop and deliver bad news.

Andrew: It’s funny, in hindsight, that the motorcycle is romantic but the bicycle is menacing!

Dylan: Also, you mention the archival footage. Has Malick ever included something like this before to your memory?

Andrew: Yeah, I don’t think he’s ever used pre-existing footage in one of his films before.

Dylan: It could be because of this movie’s basis in clear historical events. Either way, there is something unnerving when there are quick cuts moving almost seamlessly between some pre-existing and recreated footage inside cars and trains looking out. It situates the setting but creates a tension for the audience having to reconcile the closeness of the archival footage and the footage shot for a movie attempting to recreate and capture this time and place of the past.

One of the main positives for me, though, would be the performances. We can talk about Franz and the arc of his character in a minute, though the tension in that performance, on August Diehl’s face, the life and the energy gradually drained from it, held for me until the end. But really outside of some towns folk performances (that wannabe demagogue mayor got pretty wild-eyed and fiery there) and one or two small or surprise cameo roles, the performance that centers the movie for me is Valerie Pachner’s. She makes the fallout of the situation resonant: carrying the torch for her husband while he’s gone for training and eventually imprisoned; having to deal with suspicion, ire, and push back from their neighbors going so far as running them off from helping with shared land and crops; and their embrace when Franz comes back from months of training, just wanting to stay there for awhile, before telling everyone that he’s arrived home. One moment in particular from Pachner’s performance stood out to me. When Franz’s about to leave off to join the armed forces in full, she’s doing her best to convince him to stay; it’s a low angle shot looking up at them laying in a field, we can hear their kids playing just out of frame, and there is this look in her eyes, thinking, wondering what she could say or do to convince him and ultimately just holding the image of her loved one in as it may be the last time she sees him.

But ultimately it is Pachner’s look of determination and conviction that keeps the emotional arc for me even when her husband/Diehl’s face seem so pained and conflicted. Did any of that resonate with you, Andrew?

Andrew: Well let’s talk about the husband’s face, as he has essentially one look throughout the entire film – the look of stoic determination, which could also be described as resign – and that’s the crux of one of my big questions about the film. How am I supposed to feel about this guy? Is he, as Jessica said in her review, “a hidden hero”? Or is he misguided in his activism? And is the movie taking a side? Of the relatively small amount of dialogue in this three-hour movie, a great deal of it consists of people arguing with him about how his refusal to make Hitler’s loyalty oath (which is a gesture, not an action – he had already signed up to actively, albeit begrudgingly, serve in Hitler’s army) puts his family in a great deal of danger while solving nothing. Dylan, you compared it to how the film Silence depicts idolatry: care to explain this?

Dylan: Well in Silence (2016), when the Jesuit priest is interrogated by a local Japanese governor about his beliefs and eventually imprisoned for them, he is continually given the opportunity to be released if only he would step on an icon of Christ as a renunciation of his faith, but that act of apostasy for the priest is too great. It brings a tension to the fore then, as you mention, of idolatry, can the priest still claim his faith when asked to damage a symbol of it? So it is a similar dynamic, in that both of the main characters are asked to break from their beliefs and faith by bureaucratic leaders, but the context is decidedly different and the scenario plays out differently: it’s the difference between a non-native religious proselytizer without a wife and children at home in the balance and an Austrian farmer scrapping against Nazi bureaucracy while his local religious leaders think he should support the fatherland and sign the oath. Both are withering in spiritual pain while imprisoned when it could be so easy to acquiesce, but the stakes and cultural context put them in a different light.

Andrew: There’s also the argument that even by opting to be placed in Nazi prison rather than swear that oath, he is materially supporting the Nazi military via the war effort prison labor he’s forced to do while locked up; he can’t help but support the system just by virtue of being in it. And when these arguments are made – at great length and by people both for and against the Nazi cause – Franz just gives his one look, supposedly noble and strong-of-faith. This is not a character like Reverend Toller from First Reformed, whose entire worldview is whipped into a cyclone of confusion after becoming aware of tragic circumstances; Franz is determined to do what he sees as the right thing in the face of pure evil. On a Kantian level, he will not do a thing he sees as wrong (pledge the loyalty oath), even if he can’t materially affect any sort of outcome related to it. Viewed from one angle, you could see him as a Bressonian figure, like the Christ-like donkey at the center of Au Hazard Balthazar, who just takes on the suffering of the world with grace, despite being powerless to change things.

I look askance at this, though: yes, Nazis are evil and you shouldn’t swear oaths to them (hot take alert), and yes, it’s hard to keep from supporting an evil power structure once it’s fully taken hold of your world, but what about before it’s done that? We spend a lot of time in the isolated village of Radegund with Franz as Nazi rhetoric is starting to spread there, and what does he do when he sees it? Nothing. He stands firm in his convictions by refusing to say or do anything supporting the Nazis, but he does nothing to try to push back against them from within his own community. This may be crass, but another comparison that leaps to mind is Tina Fey’s “Just Eat Cake” speech that she delivered after the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville. Best to just ignore it, she suggests; those Nazis will surely go away on their own. Just eat your cake – or till your fields and pray to your God, in this case.

Au Hazard Balthazar

First Reformed

SNL

For most of the film, I wasn’t clear on whether or not Malick was inviting me to critique the character in this way or if he was holding him up as a type of uncomplicated hero figure – and I’m still not 100% sure. But the movie ends with this George Eliot quote praising “the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” And I think...um, what the fuck? I’m sorry, but you’re not heroic for silently keeping your faith while Nazis gear up to slaughter millions. I think the onus is kind of on you to do something to combat their influence? They’re not cool kids passing around a flask at your high school prom; you can’t just say no. And although no single person can single-handedly kill Hitler, Tarantino-style, you might at least do something in service of whatever small number of people you can. You know, something that is not just stare silently at people who try to talk you out of complacency? Being Christlike doesn’t just mean suffering gracefully; it also means calling out injustice and helping the less fortunate. If the movie is aware of this tension, I’m all for it as a character study and an exploration of a very particular moral dilemma. If it’s not, I wonder if this is the right story to be telling in the present moment.

And also just on a sheer entertainment level, this three-hour movie does get a little dull in the second half because the protagonist has already made up his mind on what he’s going to let happen to him, so the rest is just the slow doling out of that punishment. But Dylan, what are your thoughts about some of these ethical concerns I’ve laid out here, and what do you think about the timeliness of this message?

Dylan: It’s sad that the Bresson film that you have to pull from here is Au Hazard Balthazar (and comparing Franz to a beast of burden) rather than A Man Escaped (in which the central action of the movie is someone methodically planning a prison break), but that doesn’t seem to be the story Malick wants to tell. I give the character of Franz and Diehl’s performance more leeway than you do here, because he is seen in modes and expression than just resigned stoic seriousness: there is tenderness and love between his wife and kids, small moments of kindness between him and other prisoners, and his easy friendship with a goofy soldier (Franz Rogowski, who played the main character in Transit also this year!) whom he met during training and meets again in prison. However, I agree that once we are in the back half of the film (after the family as a whole was struggling with his decision and the Nazi pressure was still setting in), it can become a dissatisfying, moving/frustrating experience. I think this is why Pachner’s performance becomes such an important means of connection for me, as I mentioned above, and how she makes their moments of separation and reunion particularly impactful.

Even with those acts of kindness within the prison, I also agree that his actions can feel negligible and futile, which makes Franz’s path more pitiable and tragic than one of heroic aspirations. His gesture, as you call it, is still an action – but one of small impact that, as you point out, probably won’t materially change his or anyone’s circumstances other than making things worse for his family at home. As you also say, there were plenty of characters giving him all kinds of opportunities to break out of his complacency, but in this case they were all towards just signing the oath and questioning his refusal when it ultimately matters so little (e.g. his church leaders, the mayor of his town, the lawyer they gave him, a tribunal judge). So at least with what was shown to us, it was his family against the world. The transformation of the village he lives in happens so quickly and decidedly with no apparent chance of push back (a full fiery spiral by the mayor into xenophobia of unseen people, and a general complacency of the church as a whole) that it feels like the movie is trying to get across an experience and beliefs of the “average, humble” person trying to reconcile their conscience and mitigate wrong action in this tragedy. Someone who is not charismatic (or Christlike) nor able to organize around shared, status-quo-breaking beliefs has no support either in an isolated village or in prison, where we see mostly aimless hopelessness.

But with that and your reference to Tina Fey’s joking call for cake-eating, it does make me wonder about the movie’s timeliness. There are enough differences between our time and circumstances that, even though we are experiencing a reemergence of facism, our capacity to organize and find broader support outside of our immediate communities has increased (despite the same being true for fascists), as you alluded to in your response to technology above. I can find sympathy and sadness in these characters and scenario from the past that has resonances in the present, but I appreciated Transit, another movie from this year, more. Adapted and made contemporary from a novel that came out in 1942, it presented its ethical dilemmas of restless uncertain action, kindness, and compassion under a violent and oppressive regime in a way that feels more akin to the present, fleeting connections and communions with others as we try and find our way forward. It is sad, and kind of funny, then, that the actor Franz Rotowski was in both and reminded me of a movie I would rather be watching. Does that comparison make sense to you, Andrew?

Andrew: Oh, 100%. I appreciate anyone who has wrestled through this long, conflicted exploration of A Hidden Life’s underlying ideas, but at the end of the day my pithy take is that people should see Transit. Of all the films to come out this year attempting to say something about our present political dilemma, that is by far the one with the most potency and urgency.

Also, as a complete post-script, how weird is it that, like, 80% of this movie is in English? Despite the fact that it’s set in Austria, all the actors obviously can speak German, and every once in a while they just slip into it for no apparent reason? Especially due to the fact that Malick’s To the Wonder allows characters who speak different languages (English, French, Spanish) to do so freely? I dunno, it’s a stray point, but it often made me feel distanced from the performances.

Experimental Shorts

Andrew: I never pass up the rare opportunity to see an avant-garde shorts program, as films like these are near-inaccessible on the home video market and they really benefit from the transportive theatrical experience. I was also optimistic about this slate of films because it included Sky Hopinka’s Fainting Spells, which I saw at TIFF in 2018 and really enjoyed. This program also featured Gun Shop by Patrick Smith, Crude Oil by Christopher Good, Winners Bitch by Sam Gurry, Violeta + Guillermo by Óscar Vincentelli, Mom’s Clothes by Jordan Wong, Elder Abuse by Drew Durepos, We Were Hardly More Than Children by Cecelia Condit, My Generation by Ludovic Houplain, and Parsi by Eduardo Williams. One thing that I’d love to flag up before jumping into them was something that the programmer said before the screening began: he was quoting one of his former professors, who said that watching avant-garde cinema is like jumping into a pool of water; when you jump into a pool of water, you’re not judging it for how much sense it makes or how much meaning it conveys, you’re just enjoying the experience of being in it and enjoying its texture. That’s a line that will likely stay with me for a long time as I continue to explore this playful and bizarre medium.

Elder Abuse

My Generation

That said, the first thing worth pointing out about this block of shorts is that it included a lot of films that I wouldn’t ordinarily think of as avant-garde – which may be why they used the term “Experimental” instead, to denote that these are films that just don’t fit in any other category. Crude Oil, for example (a film about a love-hate relationship between BFFs who both secretly have strange superpowers), was a narrative short with some rapid-fire visual effects that really seemed like it needed to be expanded into a feature. Elder Abuse, which mostly consists of a single shot capturing a conversation between a boy and his grandmother who demands a cigarette in the most vulgar terms possible, was a really funny narrative piece with a “graphic-design-is-my-passion” visual freakout near the end, but it felt like it belonged on Adult Swim, not in an avant-garde program. The last one of these black sheep was My Generation, which is a virtual through a superhighway of American culture’s most depraved elements (it’s some real masturbatory “we live in a society” shit, especially since its ends with this toothless quote about how we should all just get along), felt like an admittedly-impressive animation reel in an art student’s portfolio.

Winners Bitch

Parsi

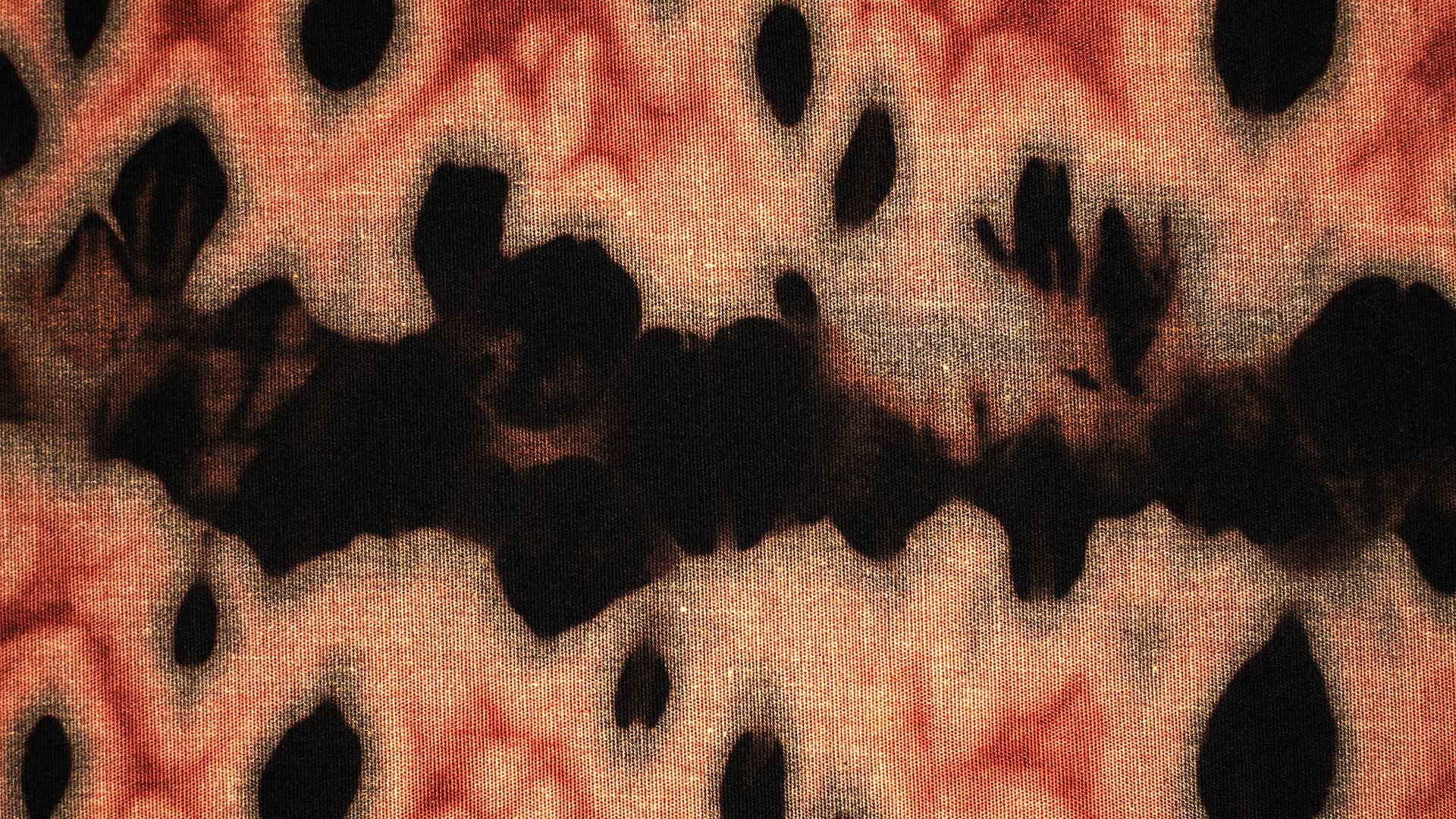

The shorts that did feel more like avant-garde experiences were of varying quality, but one thread that carried through many of them was the persistent use of voice-over narration! Of the eight shorts here that didn’t feature narrative dialogue, four of them (Winners Bitch, Mom’s Clothes, We Were Hardly More Than Children, Parsi) were constantly jabbering at the audience, which I found generally irritating, even though it worked well in certain films. Winners Bitch feels to me like the most successful of these, as a sort of visual and auditory portrait (mostly via old photographs and illustrations) of a late woman renowned for her work judging dog shows. Mom’s Clothes, which combined Jodie Mack-style animated close-ups of fabrics with a personal testimony, only really clicked near the end, when it was clear that the queer experience being discussed by the narration was directly tied to the speaker’s experiences wearing their mother’s clothes as a child. We Were Hardly More Than Children was a bit of a mess both sonically and visually, combining paintings, miscellaneous video of nature and dollhouses, as well as video interviews while the sometimes-singing narrator told a personal story about a...miscarriage? abortion? It was a little unclear. Parsi was near insufferable, though, especially as the last film in the program: shot on a camera that captures a 360-degree view and stutters like the Google Earth van cam, it was honestly pretty visually engaging – but the narration, which was a 20+ minute piece of found poetry in which each short phrase began with “seems like” drove me up the wall.

I’d like to transition into talking about the short that both of us found the most moving, but first, Dylan, do you have any thoughts about these films or others I haven’t mentioned?

Dylan: To go back to that quote the programmer gave for a sec, I appreciate the analogy for not just direct verbal meaning, but also the experience of getting used to the temperature of the water and the sensation of being immersed in it. I get this feeling while watching just about every movie – let alone strange, disorienting experimental films all doing their own thing.

We might as well start with the beginning with these, right? The programmer said they structured the sequence to go from “soft” to more out there films, and Gun Shop, though it didn’t have much of an overt narrative like Crude Oil, had the most immediate concept. From the festival guide: “There are currently 393 million firearms in the US. This film shows 2,328 of them.” It shows all those guns in quick screen-center visual comparison so you can immediately feel similarities/differences in shape and size, synchronized to a jazz drum track. Gun Shop is overwhelming and silly despite the subject matter. How is this sitting with you after some days away?

Andrew: Yeah, I really enjoyed Gun Shop – the concept of showing similarly-shaped images in rapid-fire succession is a simple one (and familiar, as it reminds me of Jodie Mack’s hyperfast tour through a mineral collection in Hoarders Without Borders), but I thought it was effective at not only overwhelming you with the sheer number of guns, but also illustrating just how much of an adaptable commodity guns are. Every once in a while, you’ll get a glance at a real gimmicky one, like the Hello Kitty pistol that’s on the film’s poster – there’s also a whole section dedicated to water guns! And although the film doesn’t present itself as any sort of overt political statement (the title card basically just says “here are some of the guns that exist”), Gun Shop, in its own small way, is probably a much more effective political commentary than My Generation. This series of images was also made much more engaging by the jazz drum score you mentioned, the dynamics of which really make it seem composed specifically to trace the fluctuations in gun size throughout the film.

Gun Shop

Violeta + Guillermo

We also haven’t talked about Violeta + Guillermo yet, which combines dance music, low-res home video of a couple dancing and then talking closely with one another, and on-screen text transcriptions of some conversation they’re having while looking back on the footage. I thought it was sweet (and I liked the music a lot), but it felt a little incomplete or slight to me – I would have liked to see an expanded version of this that presents a more complete picture of this couple’s relationship. Anything else on these films, Dylan?

Dylan: Oh my, yeah, the Hello Kitty styled guns stood out to me also, particularly when they popped up more than once! And you’re right: the commodification does not just stop with the “real” guns themselves, but also the “space-age” toy laser guns and the water squirters that you mentioned; it draws a pretty clear picture and juxtaposition.

So I agree with that comparison to My Generation – both are overwhelming in their imagery, but as you say, Gun Shop makes its comment in a much more focused and implicit way. My Generation simultaneously tries to be all-encompassing and borderline grotesque in its caricature, but it also cordons off each collection of symbols ( brand icons, famous architecture, religious symbols, surveillance cameras the veil of 1s and 0s, etc.) as if they exist independently of one another. We may be going down this CGI-highway watching these notions go by in their supposed enormity while being distracted from intermittent car crashes, but a much more interesting film to me would be how these ideas talk to one another and not in this strange separation.

And I liked Violeta + Guillermo well enough. Though I did roll my eyes a bit at the text over the screen of “the love drug, oxy-fucking-tocin.” But the music and carefree dancing gave me a different energy than where the rest of the program goes. As you said it could’ve gone a bit further, but it seems like it was going for quick and sweet reminiscence in camcorder.

I need to watch We Were Hardly Children a second time to follow more with what all it was trying in those disparate styles you pointed out, but there were those close-up shots of the beach with the water scraping and covering tiny dollhouse furniture that have stuck with me.

Andrew: I agree – and I wish the short chose those images as its central focus.

We Were Hardly More Than Children

We Were Hardly More Than Children

Dylan: This did feel like a look back at an event, with the specifics rather obscured, from one end of a lifelong friendship. The jumbled visual style and confused story felt appropriate and in tension between the two friends and how they remember that day, with one trying to forget while the other cannot. Wish I could remember more of it!

Crude Oil, with all the manic energy it was whipping up, did feel like it suddenly just ended. It finally found the visual metaphor of the one trapped friend attempting to bust out of an enclosed room dressed as a spandexed superhero to show them break free of the friendship, but as a short wanting to talk about a friend moving away and finding distance from what turned out to be a questionable friendship, I could have used to some space to process myself.

Crude Oil

Mom’s Clothes

The Jodie Mack-style landed with me also for Mom’s Clothes and made me enjoy it on that front, and considering how it ends, it seems like the filmmaker was wanting us to fixate and come to appreciate the clothes and fabric in a sort of unfolding context.

And I agree with you about Parsi – it was stressing me out by the end (particularly since it was the last film on the program), but I appreciated the strange strain in imagery (of Argentina, politicians, all kinds of flora and fauna, a reference to the show Twin Peaks, objects and cultural allusions big and small) that those “Seems like” lines evoke against the stilted but straightforward visual background of people picking up that camera and taking it through a day (?) in their village. It took me at least 10 minutes to calm down after that one.

But uh, I feel like what you really want to get to is Fainting Spells, and I don’t blame you. Outside of some moments in a A Long Day’s Journey Into Night, which we will talk about later, this took me to a different, eerie, and beautiful place. This was your second time seeing it then, right? How did it hold up for you with a year’s distance?

Fainting Spells

Fainting Spells

Andrew: Oh boy, did I love Fainting Spells. I liked it when I saw it at TIFF last year, too, but I saw it as part of a particularly stacked lineup of avant-garde stuff (which included new work from Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Jodie Mack, and Kevin Everson), so there were so many things to think about and praise that I didn’t really give this the individual attention it deserved. But viewed as part of the Nashville Experimental Shorts program – which, as I mentioned earlier, was often a little more talky than I’m used to from avant-garde – it shined.

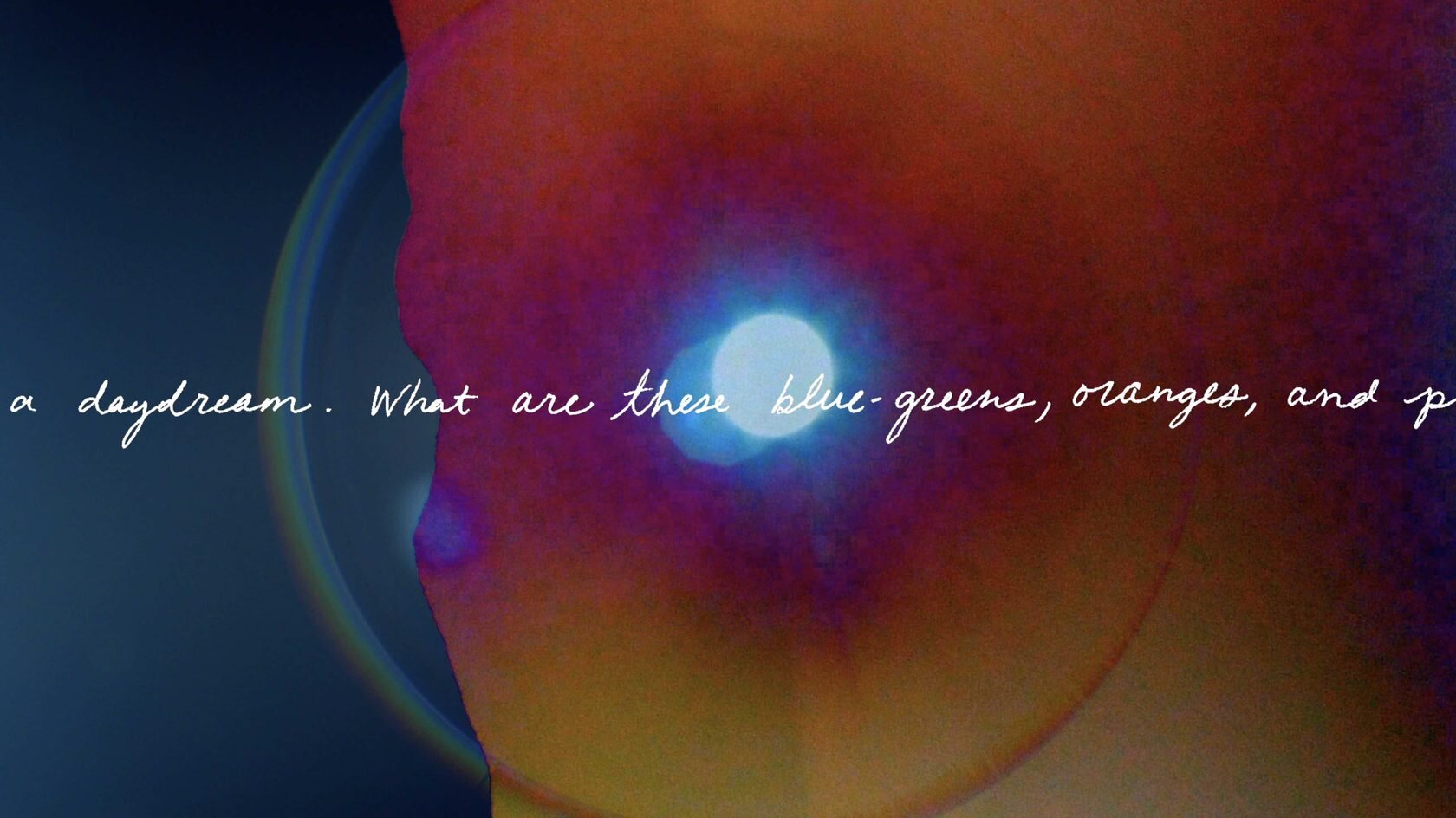

Fainting Spells is directed by Sky Hopinka, whose work, as he describes it, “centers around personal positions of Indigenous homeland and landscape, designs of language as containers of culture, and the play between the known and the unknowable.” This film in particular is framed as a story about Xąwįska, a pipe plant that the Ho-Chunk tribe uses to revive those who have fainted. The short opens on an image of an old analog television sitting in the dark, displaying an American landscape, and we hear some brief dialogue: a small child asking a parent to tell the story of Xąwįska. The parent agrees, and we find ourselves inside the image displayed on the television – and here is when the film opens up wide, stacking images of rolling landscapes and natural light to create a transcendent, psychedelic experience and is at times truly too beautiful for words, especially near the end, when a filter is applied to the image causing one half of the image to stretch out in an upwards, diagonal motion. Laid along the top of all these images are scrolling, handwritten sentences telling the myth of Xąwįska, but as I explained in my TIFF coverage from last year, the sentences are so long and winding and roll so slowly that you often forget what the beginning of the sentence said by the time you get to the end – and once the short reaches a certain point, Hopinka begins rolling in multiple sentences at once, making it truly impossible to keep up in any logical way. This pleasantly disorienting experience is appropriate given the subject matter, making the audience drift into a trance-like state of half-consciousness where processing words feels unnecessary. The words are merely part of the image, which becomes all too clear when sentences begin scrolling at the very top and very bottom of the screen, resembling sprockets on the edges of a strip of celluloid film.

I should also point out that this short is punctuated by a piece of absolutely beautiful music: a popular Navajo song called “Go, My Son” which lyrically presents a monologue from a parent to a child in which the parent waxes poetic about the importance of pursuing higher education (“go, my son, go and climb the ladder / go, my son, go and earn your feather / go, my son, make your people proud of you”). Listening to this song sung by a small, delicate voice (and played diegetically through what sounds like a thoroughly nostalgic analogue medium) in the context of a child asking their parent about Native American culture and seeing all this romanticized psychedelic imagery made for a rich, moving experience of a particular kind that isn’t really possible through conventional cinematic language. It’s everything I’m looking for in an avant-garde film, really. A new personal favorite.

You were similarly transported by this, right, Dylan? What about the experience stuck out to you? I feel like I haven’t done a good enough job describing some of the more ethereal, rainbow-tinted visual moments.

Dylan: I was. That opening (see: first frame we included up top) and tracking shot through what looks like the end of a forest fire immediately placed me in an in-between space and that was before the melding and blending imagery even starts. The middle section feels particularly difficult to describe, as you mentioned, when we are also asked to keep track of a scrolling story, but behind it, the landscape starts simply enough with brown dusty hills on the horizon turned sideways. The image stretches and flips and layers and makes negative darkened forests, cloudy skies, and sparse plains atop one another transforming what can be too easily seen as a boring landscape into an overwhelming experience with the flickering sun always circling the center. With ethereal music and the sounds of the tide rolling in, it feels closer to staring into the ever-shifting sea. This feeling continues when it seems like we end on a blue and yellow emanating scene of a highly populated beach. As the camera pans sideways, the scene is pulled and transported diagonally towards the sky that (along with the lovely song you described, Andrew) made me into a puddled mess. I am glad you wanted to see this again.

Andrew: Absolutely, me too. And I plan on seeking out more movies by Sky Hopinka whenever I can. Some are available on his website, including one called “Dislocation Blues” which is about the North Dakota Access Pipeline.

Honey Boy (2019) by Alma Har’el

Dylan: This one took me by surprise. I had not heard of Honey Boy until you told me we were seeing it at the festival, saying that it was Shia LaBeouf making a movie where he plays his dad, which promptly made me raise my eyebrows in confusion with a nervous laugh. Still not sure if that is good or bad or not, but it is certainly something to watch him to try and exorcise that up on screen. And helps with Lucas Hedges doing his best to channel Shia in his performance.

The story follows Otis at two stages in his life: one as a kid (Noah Jupe) acting in a sitcom, living with his ex-military and ex-rodeo-clown dad (Shia LeBeouf) on Otis’s per diem at a motel, and the other as an adult actor (Lucas Hedges) on big loud action films who maintains on alcohol until he ends up in a bad car wreck and is forced to either go to rehab or go to jail. And while in rehab a counselor tries to slowly help Otis confront his anger and how it is tied to growing up with his dad. The movie intercuts between these two stages to directly connect these parts of Otis’s life and reconcile the character of his dad. That sound like the long and short of it to you?

Andrew: Yeah, that’s the gist of the two parallel stories being told here – with the adult half set in rehab serving as a much slighter frame for the primary narrative about Shia (sorry, I mean Otis! obviously) as a kid. The cutting between the two sometimes feels a little random, as there isn’t much going on in Lucas Hedges’s story other than frustrating conversations with his therapist and other rehab assistants. Within the childhood narrative, there’s a really intense dynamic between Shia (er, Otis!) and his dad that is a lot more nuanced than what we usually see represented on screen when it comes to abusive parents and victimized children. For most of the runtime, it dwells on the toxic nature of their relationship as it existed before dad ever hits him – he is verbally abusive with his constant barrage of angry obscenities, he is emotionally/psychologically abusive with how he wields/leverages the kid’s relationship with his divorced mom (at one point making Shia/Otis swear at her on his behalf over the phone), and overall dangerously negligent/permissive in the way he grants his kid access to alcohol and cigarettes at a young enough age for him to become more easily dependent (which circles back to Lucas Hedges in rehab).

Shia’s perspective when looking back at these events is neither vengeful nor nostalgic, and the stance he ends up taking is an interesting one that may resonate for some child abuse survivors and may strike others as somewhat unrelatable: the son, both as a child and an adult, is in a very tricky position of craving love/validation from his abuser, needing to express that love without necessarily forgiving the abuser’s actions. The film’s few scenes away from Shia’s character (Otis!) also gives credence to the axiom “hurt people hurt people” and finds rationale for why the father is so unstable in the first place (his war PTSD, his poverty, and what is most likely another ambiguously-related and untreated personality disorder).

Dylan: For clarification, I describe the dad character in the intro as ex-military, but we never actually get clear indications of it. Ex-rodeo clown for sure – there’s all the odds-and-ends tricks (sock juggling and card gimmicks), the story and joke of the rooster act he used to perform, and the sequences when he is in full clown costume and makeup – but we only get loose signs of military service (stories he tells in AA meetings; the jacket and vest he wears throughout the film; and signs of trauma and a potential personality disorder as you mentioned). But we hear later from Otis that his dad makes up a lot of those stories, cobbled together from others’ stories he heard in AA and jail, and we never get flashes of a wartime experience like we do with his rodeo days, so we should take these with a grain of salt. Though to be sure having to make a living and play the part of a rodeo clown while also wrangling with large dangerous animals all day, I can easily believe that that life can leave you with PTSD.

Andrew: I went into this expecting a deeply uncomfortable, quasi-provocative art stunt (what else can you expect when you hear “Shia LeBouf plays his abusive father!”), but I was surprised at how tender and thoughtful this movie was. It’s also true that stories about men openly processing trauma (and crying through it!) are and always have been fairly uncommon, so I’m glad this movie exists regardless of how great it is on any craft level. It’s still a festival-ready Ameican indie drama, so there is kind of a low ceiling to just how amazing of a viewing experience that can be (it’s not Malick, y’know?), but there’s a lot to be grateful for here.

I’m still mulling over my thoughts on the fact that this story necessarily places its highly relatable abuse narrative within a highly unrelatable context of child stardom (and really deglamourizes that even financially – these characters are dirt poor, so thanks, Disney, for treating your employees well). It was a hard movie to watch without constantly comparing it in my head to Sean Baker’s The Florida Project, which is more about poverty and neglect than outright abuse, but has a lot in common with this movie in the way it examines that experience through the perspective of childhood naivety. Dylan, you hadn’t seen that film until I mentioned it, but you then sought it out, so I’m curious how that comparison strikes you and how you’re feeling about the specifics of Honey Boy.

Dylan: There is a bit to the comparison in how these relationships are put under pressure by living in precarious conditions and how children try to adapt and navigate through them, but there are a good deal of differences. There are different gendered dynamics and expectations in father-son, mother-daughter relationships and how they are enacted within them and have to contend with others’ projections of them. And in these cases, you get a difference in the level of permissiveness and leniency from the parents. A distinction you brought up yourself. Otis’s dad is more domineering and demanding, while Moonee’s mom lets her wander around, get into mischief, and do just about whatever she likes. And also there’s the way money causes the parent-child relationship to change: Otis and his dad for the most part have to live off the money Otis makes from his acting while Moonee and her mom are just getting by on gifts, favors, selling wholesale perfume, and her mom eventually going into sex work. And finally I think the kids’ age difference (Moonee is six in Florida Project and Otis twelve is in this one) brings out different coping mechanisms and energy despite both being sensitive, intelligent kids. Moonee has the energy and imagination of a kid who has been left to her own devices with the restless, potentially destructive energy of a six year old, while Otis is a child actor who seems like he has mostly been brought up on sets and his energy and sensitivity are more focused and contained. Ultimately, where Florida Project leaves off is more uncertain and ambiguous in what happens to Moonee than Honey Boy where the character of Otis is from the jump given ten years for us to compare and reconcile with. But after we got out of the movie, you did bring up the interesting notion that these are directly, or not, set around Disney in one way or another. Has that idea developed any further for you?

Andrew: Yes, thanks for highlighting that point. I think the proximity to Disney is important for both films in as far as they’re both offering very non-Disney-fied realities of what “family” means for many kids, considering how much of Disney’s branding is wrapped up in some platonic ideal of family entertainment. The Florida Project leans into this much more energetically (that last shot!!! electrifying) than Honey Boy does, which makes Honey Boy feel a little limp-wristed in comparison, although I know it’s going for something different. Still, Shia LeBeouf was literally on a Disney show about a much more charming dysfunctional family – Even Stevens – and I kind of wish they had played up the fiction/reality parallel a bit more than they did. It’s in there for one or two scenes, but…

Dylan: Right, we get one really unnerving scene where Otis daydreams a heart-to-heart with his dad as he watches a heartfelt episode of the sitcom Otis’s on and the dad starts saying the lines but in the voice of the TV dad! But most of the relationship is “grounded” in the day-to-day reality of living with his dad in a motel and having to prepare for the show. Real tension comes out of that, but the playacting and pretend is mostly underlined by the “meta” casting of Shia as his dad and having to interact with Noah Jupe as a projection of his younger self.

Andrew: Speaking of: the “I’m gonna make a movie about you” line at the end was a little much. But on that note, perhaps it’s also worth mentioning here that Honey Boy is an interesting case for challenging auteur theory – considering “I” is the active subject of “I’m gonna make a movie about you” as well as a lot of other aspects of this movie, it’s very clear to me that this is Shia LeBeouf’s movie, despite it being directed by Alma Har’el, whose name I might suspect was a pseudonym if I didn’t know better. Does Shia-as-Author seem right to you, Dylan?

Dylan: In part, for sure – in interviews, anytime Shia takes part, he is the center of the conversation and clearly the story since he wrote it himself. But a lot of credit and collaboration is also given to the other actors and Alma Har’el for shaping the project from the beginning (Shia wasn’t going to play the dad until she convinced him otherwise!) as soon as he finished the script, conditions on set, and apparently contributing to the writing through improvisation and the like during filming. Also for surprising stunt roles, FKA Twigs was cast as “Shy Girl” who lives in the motel room across from Otis and his dad. They find affection and relaxed friendship between each other, something that may be displaced without his mom around to offset his dad’s energy. And speaking of the mom part, apparently Natasha Lyonne plays Otis’s mom? Outside of one or two phone conversations that devolve into shouting matches in which we can barely hear her side of the line, one wouldn’t know it! Though for sure from the outside as an audience member, the biographical overlap and casting can make it hard to interpret this as anything but a stunt, which it still kind of is.

And as a last side note: what’s up with the dad’s wardrobe in this? Shia looks like ‘90s David Foster Wallace blended with ex-rodeo clown and a dash of biker. No idea how to process that...

Shia LeBeouf in Honey Boy

David Foster Wallace

Long Day’s Journey Into Night 3D (2019) by Bi Gan

Andrew: I am absolutely thrilled by the fact that Nashville was able to present Chinese slow cinema innovator Bi Gan’s new film as it was intended to be seen – with its astonishing, almost-hour-long final shot projected in 3D – even though I wasn’t able to attend the screening myself. I have seen the film twice this year already, however (once in 2D, once in 3D), and even wrote a full review of the film for Arts Knoxville, in which I summarized the plot incorrectly, sorry – it’s a difficult film! Anyways, this is undoubtedly one of my favorite movies of the year, so I’m eager to talk with you about it, Dylan. Am I right in assuming this would be 100% your shit?

Dylan: Yeah, I am glad I got the opportunity to catch this after missing its original theatrical run! And even though I will miss the 3D, it will probably be a movie I watch again before the end of the year (if I can!) to pick up the pieces I missed the first time. Also glad I caught Kaili Blues, Gan’s feature before this one, a few days before to get a feel for the writer-director’s sensibility. If I hadn’t, Long Day’s Journey would have still taken me on a beautiful ride, but watching the previous film allowed me to appreciate more this two part structure Gan seems to be playing with in both. And seeing all the wide-angled, encompassing cinematography in Kaili, I can see why Gan and the three cinematographers credited (Yao Hung-i, David Chizallet, and Dong Jingsong) in this movie would be interested in experimenting in 3D. Before we get into, I am curious how did you first see it, 2D then in 3D? How did it play that second time? Well enough to be one of your favorites of the year, I guess!

Andrew: I saw it on a 2D screener first and then via 3D projection the second time round – it was a beautifully textural experience even on a small, flat screen, but the final hour became far more mesmerizing and immersive in a darkened theater with that added depth. The one moment I remember most vividly from my 3D experience was that shot of the protagonist going down the chairlift, slowly being lowered down into this carnival-esque glittering night scene. It really felt like the film was pulling me into the screen as the character was steadily and mechanically pulled along this single downwards trajectory.

It’s also the case that I was able to follow the film a lot better the second time around. In my initial review, I compared it to Vertigo (I mistakenly thought there were two different women he was pursuing, when in reality there’s just the one – and then another version of her in the final hour’s 3D dream sequence), but the better comparison to classic Hollywood to make (the film does feel very classical, at any rate) is Out of the Past, with the protagonists of both films attempting to “save” a woman from her romantic entanglement with a criminal and subsequently getting sucked into what feels like an endless spiral. It feels appropriate that this film ends with a magical realist moment as the set spins in one direction around the characters – locked in a kiss – while the camera spins in the opposite direction and we’re left with an uneasy, uncertain feeling of whether or not to feel happy about what we’ve just witnessed. I have a hard time not just talking about that last 3D hour, but it’s such a stunning accomplishment in filmmaking. The whole film is gorgeous beyond gorgeous, though!

Dylan: Both of those comparisons taken together are not entirely mistaken. There is plenty of doubling going on outside of just Wan Qiwen, the woman Luo Hongwu is trying to find, and the opening with the Luo returning home for his father’s funeral only to be taken in by his hometown with memories of his childhood friend’s, Wildcat, death and questions about what has happened to people he has lost touch since he’s been away. And Huang Jue’s performance as Luo, with that gravelly voice, is as melancholic and persistent as any film noir protagonist.

With only a name, blurry memories from his childhood, and a cigarette-burned photo of Wan Qiwen as a little kid, his search begins with rumors and a story of her apparently finding herself in on a heist gone bad, as told by a jail mate still in prison (Luo hoping she would recognize something in the name and photo). With only enough time to take one thing with her (“steal the most valuable possession you can find”), Wan Qiwen decides on a book with a spell written inside. When her heist-mates come back together, they all gather round wondering why she picked a book of all things. She says I took it because if I read this spell out it will make the room spin around them. As you say, Andrew, with the fractured editing of the first half and loose trail of clues, the mystery in the first half feels like being taken into a spiral of ambiguity. The trail leads him to talk with Wildcat’s mother (Sylvia Chang) and to meet a mysterious woman in a shimmering green dress (Tang Wei). He’s certain that he recognizes her, but she has never heard of Wan Qiwen ( “couldn’t be me; that sounds like an actress’s name”). He’s ultimately caught by a mysterious smoking gangster in white, who has eyes on the woman in green. His pursuit seems to take him into an eternal night, vibrating with color and rain.

It’s a calming wonder, then, when he makes his way into a movie theater and a dream, in which things feel cohesive and meaningful, with an uncanny feeling though that the people he has never met before feel so familiar to him. I agree with you, Andrew: I enjoyed the descent into the town below, but I was also taken by the gradual adjustment into 3D and how goofy it kind of was. The 3D second half fades in on Luo, with his back to the camera, riding a handcar through a tunnel, then turning his head and looking into frame as if he is slowly realizing where he is and what he is doing. This image has a strange perspective to it. It is angled with the track and handcar going into the center of the frame through a cavern passage, but it is almost 2D and 3D at the same time, with only the central movement and cavern walls going by to give you a sense of the 3D. It leaves us in this perspective until Luo reaches the end and eases his way into a darkened what seems to be a lived-in space within the cavern with only a match to light his way. From there, we get plenty of amazing coincidences in timing and movement (an ominous table tennis game, a fight with some poolhall punks, a billiards game, flying over the town, a karaoke contest, a redheaded woman ditching this small town, a spooked horse pulling a cartful of apples, tracking people into unexpected encounters, and that stunning last sequence Andrew mentioned at the top) all simultaneously seem so well choreographed but also feel left to chance as if they were stumbled into, which only adds to the movie’s dreamy sensibility. I hesitate to be too clear about this section, but this movie is difficult to ruin even if you know the events that happen in it.

Andrew: How could I have forgotten to mention that flying sequence! Ugh. It’s incredible.

Dylan: Still though, I do find it curious that a lot of reviews and interviews I have seen for this movie so focuses on the second-half, happily enumerating the concrete events. I am no exception. The first half feels like it slips though as I try and recall more and more of what happens. Specific images and impressions have stayed with me: the lingering long tunnel shot where Luo tries to talk to the lady in green that feels like it is raining inside, the room that is perpetually flooded with Luo staring into a lamp hanging over head, Wildcat’s mom playing Dance Dance Revolution while she waits for customers, the contained front-framed conversation between Luo and the woman in prison, and a young Luo staring into frame trying to hold back tears as he eats an apple whole.

These are only some of the moments that make me go back and experience this whole movie again before year’s end. What Gan trades up for the overt, verbal poetry and agitated movement in Kaili Blues are the nocturnal dream images and lingering melancholy in Long Day’s Journey into Night.

Atlantics (2019) by Mati Diop

Andrew: As I alluded to at the beginning of our Long Day’s Journey into Night dialogue, I had to leave the festival a bit early and wasn’t able to catch the last few big titles, unlike Dylan, who lives in the area. Dylan, I’m really curious to hear about Atlantics, which screened at both Cannes and TIFF earlier this year – how was it?

Dylan: I did not know much about Atlantics going in. I heard some general positives things and noticed it was on the program, but nothing in detail beyond it is set in Dakar, the capital city of Senegal, and there’s something up with a tower. As one of the last two films I saw for the festival, Mati Diop’s feature debut, Atlantics, was not a bad way to close things out.

Can confirm there is indeed something up with a tower – a futuristic tower, even. It opens on laborers working on the tower of the future in the intense heat and the dust. We see the modern glass tower in contrast to the concrete and clay buildings around it, set against the Atlantic coastline. At the end of their day, they go to the site development supervisor and demand their wages that they have been denied for what makes 4 months. Here we are introduced to the character of Souleiman (Ibrahima Traore), who alongside his coworkers is vocal about the need for their due. This is not just a matter of working for themselves and their wages; they need it in order to provide for their families. The supervisor explains the owner/developer is not in town right now and unavailable to provide, but he tries to assuage their worries telling them he will be back and they will get their wages. Unimpressed, Souleiman and a group of his friends and coworkers leave saying not to worry they won’t be back.

Trying to keep in good spirits they drive back to town singing along the way, but after that argument for their due, the beautiful, unnerving theme of the movie creeps in along with shots of the raging swells of the sea, a foreboding of things to come. We get a reprieve from this pressure when Souleiman meets up with Ada (Mame Bineta Sane) where they try to be alone together away from friends and family, but are caught by the owner of what they thought was a secluded building and Ada promises to see Souleiman later that night at the club. Before they part ways, Souleiman gives Ada his necklace as a gift.

We split off and follow Ada and quickly find out she is arranged to be married to Omar (Babacar Sylla). Her friends, besides Dior (Fatou Sougou) a close confidant, and family feel that this is the beginning and end of the matter. Ada heads out with friends to their usual hangout at Dior’s club and finds that all the boys left for Spain on a fishing vessel in the hopes of finally getting some money, leaving the energy at the club cold. Distraught that Souleiman didn’t tell her where he was going or say goodbye, Ada drags her feet in spending time with Omar and going through with the wedding.

The night of the wedding, everything seems to be going to plan, despite Ada later leaving the party and Dior trying to have a heart-to-heart with her, when someone breaks into their conversation to tell Ada that Souleiman is back. Ada in shock tries to get them to tell her how do they know and where he is, when the wedding night comes burning down as the wedding bed is set on fire.

The movie morphs into a police procedural and mystery with a young ambitious detective (Amadou Mbow) trying to find Souleiman as the main suspect for the fire and certain that Ada knows where he is, and Ada searching for him to just try and figure out what's going on, while all the girls in the neighborhood start to come down with a fever and disappear at night only to wake up in their beds with dirt splotched clothes and feet.

Diop’s collaboration with Claire Mathon and Fatima Al Qidiri (cinematography and music, respectively) really holds the movie’s unsettled atmosphere together. The story on land gives way to shots of the ever vibrating sea that builds on a color scheme of teal blues and amber and burnt oranges encroaching slowly into scenes and mixing with the score to keep you just on the outside of comfortable in the narrative. There is a stunning shot of the setting sun on the sea that makes me wonder if Mathon and Diop had Rohmer’s The Green Ray in mind. Mame Bineta Sane, as a seventeen year old Ada corralled into a loveless marriage and worried about the future and whereabouts of the one she loves, embodies a despairing and desperate energy pushed against a fevered and anxious performance by Amadou Mbow as the young detective all barely held in check by steady performances from Ibrahima Traore as Souleiman and Fatou Sougou as Dior.

Make this one to check out at the end of November if it is playing at a theater near you – otherwise, it will be streaming on Netflix. I am interested to see where Mati Diop goes from here.

Mickey and the Bear (2019) by Annabelle Attanasio

Dylan: This was the movie I noticed in the program, Andrew, that I turned to you and asked, “isn’t that the actress who was in Never Goin’ Back??” (a comedy of misadventures between two stoner friends we both liked from last year). We missed earlier screenings of Mickey and the Bear, but when I saw it was having an encore screening on the last day, I decided I should take a chance on it before it potentially disappears into a streaming service and who knows if and when I would stumble onto it again. I am glad I did. Mickey and the Bear, scheduled in the “New Directors” Features and Annabelle Attanassio’s debut feature film as writer-director, gives the two actors at the center of the story plenty of space and opportunity to build off one another and push right to the end.

On the verge of graduating from high school and deciding what path next to take in life, Mickey and the Bear focuses on the daughter of a veteran, Mickey (played by Camila Morrone), who takes care of her dad (James Badge Dale), the household, her school work, and a part time job, ever since her mom passed away. The movie opens with Mickey going through the morning routine of making breakfast/coffee, making sure her dad’s daily medicines are in order, and seeing him awake before heading to school, until she gets a call from the sheriff’s office letting her know that her dad, Hank, was taken in again. She throws on clothes and her dad’s old army jacket and rushes out to pick him up; worried about bail cost and if her dad got himself hurt again, Mickey sees him chatting up the officers on morning duty and telling tall tales. When Hank sees Mickey in the doorway watching, he says through a grin, “you’re wearing my jacket again?” The sheriff tells her the bail fee is waived, just make sure he gets home safe (and to not let him drive). Relieved to see he’s safe, on the way out the door, she throws him the keys, “you drive.” That kernel dynamic and tension are what try to maintain balance or, at least, find a release valve throughout the film.

On the roaring drive back home, we get a diorama montage cut to blasting pop music of the small town of Anaconda, Montana, a town square, library, beautiful old movie house, colorful weathered houses, the high school, and a well-neoned bar, until we make it back to their manufactured home. Besides one song in particular that gets run through a gambit of mixed emotions, the soundtrack brings out and underscores an interesting tension. It is bombastic and full of energy, but set to images of a small town surrounded by beautiful forested mountains, it makes the people and the activity in the frame seem even smaller, particularly when these moments pass and we are left with the long roads and distances that characters have to travel to get anywhere outside of town. This potential for smallness and isolation gets carried further with the positioning of some technology in the movie used to pass the time: the dad throughout the day playing first-person shooters and Mickey at night watching videos on her laptop in bed.

The three characters that form the push and pull for Mickey besides her dad: her high school boyfriend, Aron (Ben Rosenfield), with whom there is an assumed trajectory of marriage and kids after graduation; Wyatt (Calvin Demba), the new kid in school, from the UK, living with his aunt and uncle; and Leslee (Rebecca Henderson), a psychiatrist at the local VA hospital, who worries about Mickey, how she will end up if she stays in the same town still taking care of her dad, and so never leaves to find a life of her own. Aron she has to keep her eye on because he has a penchant for just taking the rest of her dad’s painkillers a week before his prescription can be filled. And after a falling out with Aron during a lakeside party where he tries to force her into sex, Mickey starts to hang out more with Wyatt; they quickly become friends and find out that they both want to go to colleges in California, Mickey for marine biology at San Diego City College and Wyatt for piano performance in San Francisco. But Mickey pushes the thought out of her mind saying she will probably be stuck in this town, she has to take care of her dad, and besides they would have to provide financial support, even with all the money she has saved up from her part time job. And Leslee, as the last corner of this triangle, tries to get Mickey to square how much pressure and responsibility she has taken on and that she should be able to find a life for herself outside of her dad and this town.

But the main engine of this movie is the dependent relationship between the father and daughter. When confronted about what she is going to do next and easily falling into the notion of staying in town, Camila Morrone’s performance makes this feel like a constant internal struggle. It’s carried in small eye shifts in close up (sometimes we are unsure how much the people around her are picking up but the audience can see her carrying that weight as best she can) and you believe through the whole runtime that because of the love for her dad, that staying is a crushing but clear possibility. And this painful dance would not work without James Badge Dale as Hank. There is enough clear love between them (e.g. that sweet, sad dance during her 18th birthday at the neon karaoke bar set to aforementioned song full of mixed emotions, and easy glances of attention and affection throughout the film), but when he is so dependent on her for comfort, care, and money, along with his post-war restlessness onto malaise, that when he’s been drinking all day or waiting up all night wondering where Mickey’s been, the anger, confusion, unsettling jealousy, and quick shifts in mood and body language (which can feel claustrophobic and invasive in the film’s blocking and composition) break through the baseline of love and the fact that she is his teenage daughter. I am glad Annabelle Attanasio decided to have this story told mostly from Mickey's perspective.

Andrew: I would like to catch up with this one later in the year if possible, especially because the Nashville Film Festival named it one of its picks for “Best of the Fest.” Speaking of…

BEST OF THE FEST

Andrew’s Pick

Long Day’s Journey into Night will likely rank very high on my “best features of the year” list, but even so, I really think the standout cinematic experience of the festival for me was Sky Hopinka’s short film Fainting Spells, which should come as no surprise to anyone who read through our analysis of it. I’m not 100% in the loop on who is and who isn’t a “big name” in avant-garde cinema, but it’s clear to me just from this one film that Hopinka deserves to be considered one of the greatest talents working in the medium today.

Dylan’s Pick

It is a nice difficulty to have trying to pick the “best” of the films we watched. There were some solid, interesting debuts (Atlantics and Mickey and the Bear) and movies that inspired a lot of complicated conversations (A Hidden Life, the Experimental Shorts program, and Honey Boy). But I am gonna have to go with an impulse choice: Long Day’s Journey was something that, as soon as it was over, I had a strong urge to watch again immediately (well, that is, after I collected myself a bit first). I can’t say for sure whether it is the best 2019 movie I have seen (I am gonna need some time/distance and an eventual rewatch first), but the disorienting though hypnogogic first half and the luring 3D experience of the second half made me glad I had the opportunity to see this in theaters. The programmer for the “Graveyard Shift” movies mentioned with pride that, as soon as they saw it during the festival circuit, one way or another they were going to screen it at the Nashville Film Festival. I am glad they did, as it was the most refreshing experience I had at the fest.