Retro Review by Zach Dennis

It doesn’t explain what the monolith is.

Or the Louis XIV room.

Or the Star-Child.

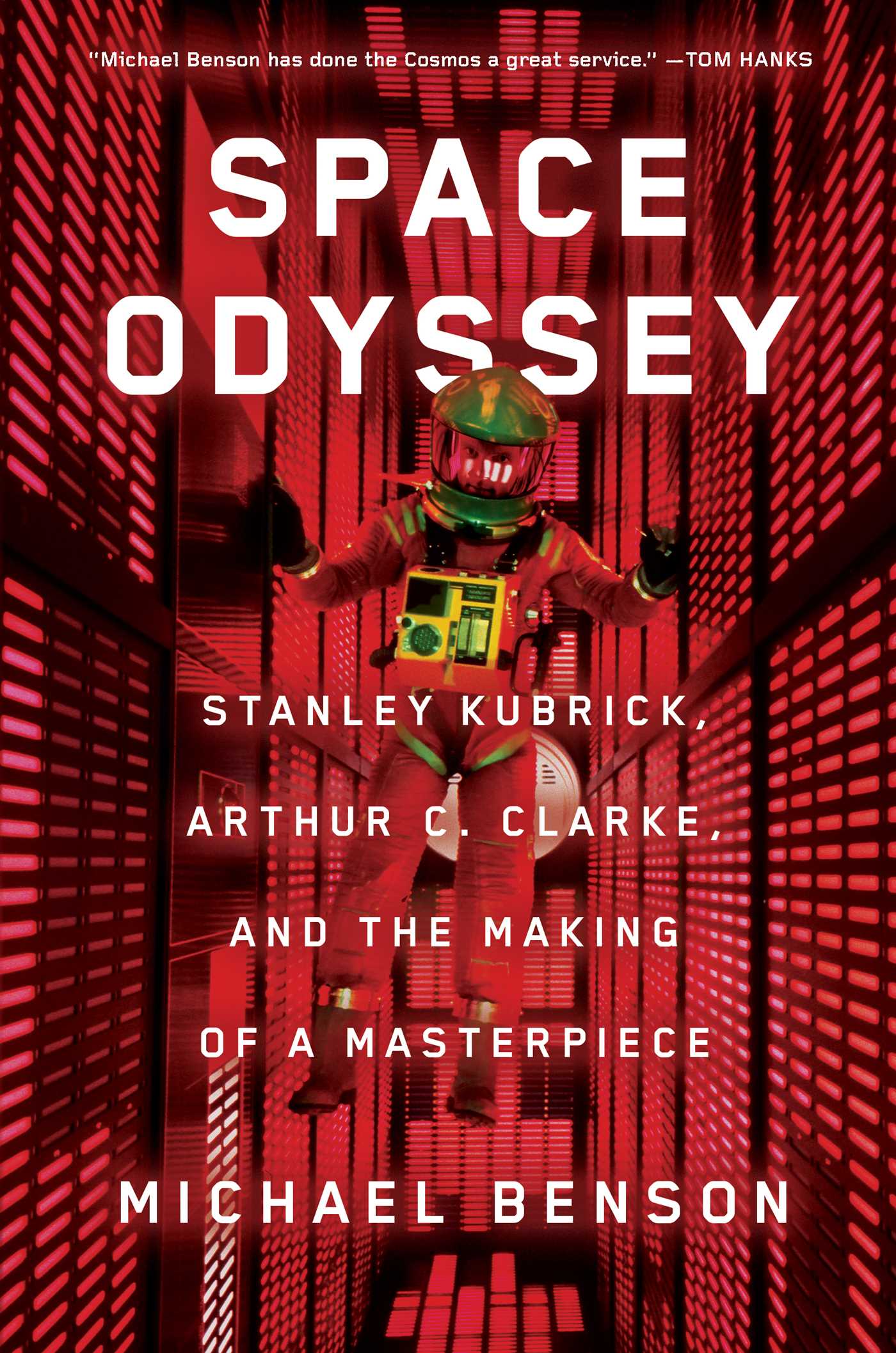

But those weren’t even the most enigmatic elements of both the film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the corresponding book, published this year from author Michael Benson, titled Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece. That title was held by not only the first name you see in the book title, but also the film's opening reveal.

Writing about 2001 even now feels in tune with a Reddit thread parsing through every inch of an episode of Lost, Game of Thrones and Westworld — seeking answers to questions that were never meant to include a response. That was Kubrick’s nature, and this nature is what acclaimed science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke picked up on as he set about crafting the film alongside Kubrick when the director reached out to him.

The first portion of Space Odyssey follows this courtship. There is pedigree behind both names, but there is something pervasive and idiosyncratic about Stanley Kubrick that even Arthur C. Clarke, who was equally as well known, was flummoxed by his tendencies. As Benson notes in one anecdote, the science fiction writer once one-upped both C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien in the halls of Oxford about evolution, but still spent many messages and conversations revelling at the intellect and skill of the Dr. Strangelove director.

In many stories, Kubrick and Clarke are holed up in the director’s apartment, parsing through book after book on theoretical physics, the nature of reality and the evolution of man. All of these elements would find their way into the eventual movie, but nobody was sure how they would come together quite like Kubrick.

One can try to understand the monolith or the final, embryonic voyeur of Earth or many of the other points of debate that have ravaged minds after viewing 2001: A Space Odyssey since its release on April 3, 1968, but to understand those would be to understand Kubrick, and through the more than 440 pages of Benson’s book, it was pretty clear that you had a better chance of figuring out if the black towering pillar was in some way God than to know who truly was Stanley Kubrick.

Cinema’s magic has always lied in the mechanisms that make it work. From the early work of the Lumieres and Méliès to Keaton and Chaplin to the mechanical shark in Jaws and the world of Pandora in Avatar, there is always that bewilderment at how it was made and whether or not that removes the sheen of the majesty that the moment manifested. Benson’s book does good work of exploring what made 2001 sheen — with interviews ranging from Kubrick’s wife, Christiane, to many of the actors and behind the scenes wizards who created the moments of visual ecstasy in the film — it feels like no stone is left unturned.

But there’s something still incomplete, and that is to no fault of Benson’s. 2001 is a film to marvel and lash out at. The ape men during the film’s opening sequence, titled "the Dawn of Man," wrath and flail at the black monolith that appears in their home, and we do much the same as we attempt to wrap our heads around the metaphysical tapestry that is the loose narrative of 2001.

Following the Dawn of Man, we move thousands of years into the future (thanks in part to a match cut of truly epic proportions) where man has since advanced to the moon and a team of scientists have discovered a similar monolith on the lunar surface. Fast-forward again 18 months and a duo of astronauts, and a eerily emotive artificial intelligence unit, make their way towards Jupiter on another mission marred in mystery.

One could simply dismiss 2001 as being plotless, or even meaningless, and to an extent, they wouldn’t be wrong. But that harkens back to our limited acceptance of the effervescent and celestial, the unattainable and un-understandable. And in these terms, it seems in these terms both Kubrick and Clarke marked their quest.

The scenes in Benson’s book of the two men slowly unraveling what would become one of the greatest cinematic achievements of all-time have all the romantic twinges of pure, unbridled creativity. Long days uncovering points in various scientific texts that would lead to unforgettable moments allowing you to become swept up in the insanity of the entire ordeal, and in this way, it is easy to relate most to Clarke — a man who was a titan in his own rights, but clearly felt close to plebeian next to the mighty Kubrick.

Clarke and Kubrick in a publicity still for 2001

As the production shifts to the U.K., and actual filming commences, the book’s narrative loses that jovial comradery as both men are in separate realms — often fighting over the corresponding book’s release or other minor details such as voice over narration that would later be dropped from the film entirely.

Make no mistake — while it says the film was written by Kubrick AND Clarke, there seems to be a chef and a sous chef, and the former was balancing a camera as well. Often it becomes difficult to value Kubrick in such esteem as anecdote after anecdote paints a somewhat tyrannical presence that demanded the perfection he knew he could achieve.

Almost as mystifying as the film itself is the production and minds coming together to build it. From Doug Trumball’s meteoric rise due to his work on the visual effects of the film, to the extensive study and dedication by Dan Richter on bringing life to the ape men of the Dawn of Man to the even more strident dedication by Stuart Freeborn to design each costume as lifelike as the next.

But they all came back to this one man. Simply he could be seen as some omniscient god striking down judgement and scorn, but these accounts always gave a defense to their deity. Like parishioners validating the acts of their Old Testament supreme, quote after quote from many of the workers behind the scenes showed that while frustrated at the time with the scrutiny and demand for perfection by Kubrick, they couldn’t help but revere the chance to work for the man.

And it wouldn’t seem like he was someone to quickly dismiss as a monster. As many stories showed, he was a shy, pensive person who abhorred doing any sort of hallucinogen as he didn’t want to affect his skill.

Maybe this is what makes 2001’s lexicon so initially disappointing. We don’t find God or supreme understanding, we find Kubrick. We find a man who had the ability to craft a true capital-C, capital-S cinematic spectacle that left us breathless and unsure of what it was all for, but it also revealed to us a man who was human in every sense of the word — sullen, remissive, tender — and not some pansophical wizard.

Pure humanity is the greatest disappointment of them all.

It is easy to think back most to the radiance and psychedelia of the Star Gate sequence, the grace and beauty of the “Blue Danube” scene or the horror of HAL’s immediate turn. But the scene that seems to prevail over all others features Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) making his way through the mind of the artificially intelligent terror after it has cast his partner out into the space and to his death. As Bowman moves towards HAL’s central nervous system, the computer pleads with its human companion to stop what he is doing and to not kill him. As his memory fades, he is suddenly rebooted for a second and asks Dave if he would like for him to sing him a song that he learned. Dave complies, and we watch as the lights go down and the program’s voice more and more distorted.

It is difficult to feel sympathy for a murderer, much less one that isn’t even of flesh and bones, but there is something sad and moving about the slow descent into nothing that HAL takes. This automaton carried every answer to every question, it featured irrefutable efficiency, and in the end, it succumbed to the most basic, primal human emotions of anger and jealousy.

As life fades from its programming, we don’t discover what answers lay within, why he did what he did. Instead, we are whisked once again into the abyss, journeying further into the unknown and the chaos of the beyond — still as answerless as we were when the bone was tossed in the air.

It may be an unanswerable enigma, but that doesn’t make 2001 or its creator any less empathetic or human. If anything, it makes both film and maker even more impressive.

Perfection is something unattainable and merely idealistic, but there is something truly absolute about 2001, a transcendence of purity. Its curious yet forthright, audacious yet small, fearsome yet gentle. The contradictions fit its creator, again, a man filled with self-assurance of his craft but anxious of his role in daily discourse.

This is what’s to love about it. Nothing is perfect, but nothing is 2001 either.