Festival Coverage by Andrew Swafford and Michael O'Malley

For four days in March, the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, Tennessee combined a line-up of avant-garde musical and film acts. Andrew and Michael were able to catch a number of the films shown during the festival, including the 3D programming curated by The Public Cinema. Since this piece is just them talking through their reactions, a general SPOILER warning for all films discussed...

Andrew: One thing that I began to notice over the course of Big Ears 2018 was how most films in the program made neat pairings--either the films were screened as a double feature in the same block of time (like the gross-out comedy of Polyester and Jackass 3D), or they were sister films screened on different nights (like Carnival of Souls and Night of the Living Dead, both screened as “late shows” for the cult horror crowd). Many of the shorts programs seemed to share DNA with the features, as well! I think it would be interesting to look at the Big Ears films as being in dialogue with each other, since there’s clearly a lot of overlap between them. I also think it would be helpful to work through these films from the most concrete to the most abstract (roughly), so let’s start with Carnival of Souls and Night of the Living Dead.

Carnival of Souls (1962)

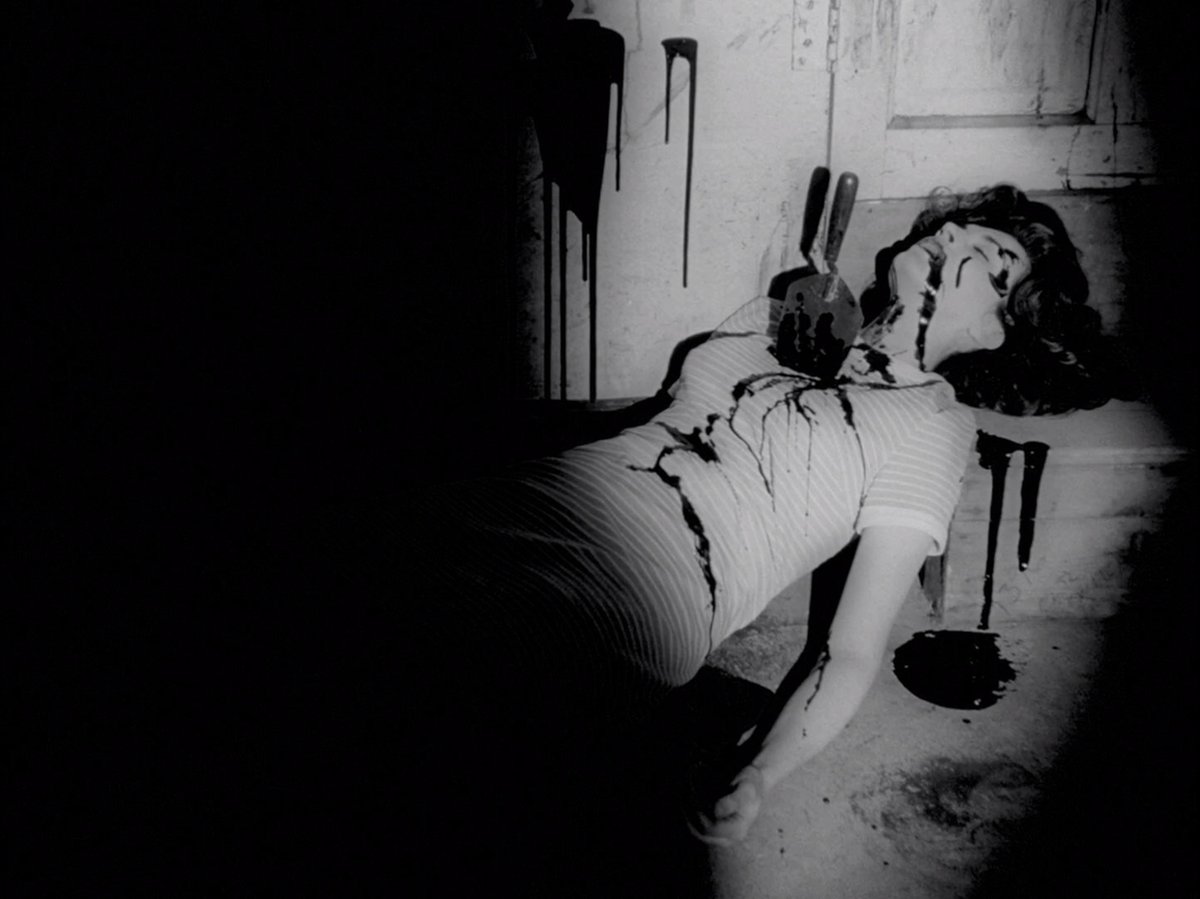

Night of the Living Dead (1967)

Carnival of Souls (1962) by Herk Harvey // Night of the Living Dead (1967) by George A Romero

Andrew: Stone-cold classics of low-budget horror! Both of us had enjoyed these movies in the comfort of our own homes before--I actually wrote extensively about them for Arts Knoxville last month--so I’m curious to hear about how they played differently in a full-sized theater (especially being late into the evening). For me, Night of the Living Dead functioned just as I expected it would: like a jackboot to the stomach, considering the politically weaponized ending. (I mean “politically weaponized” in the best way, of course.) I was not quite expecting, however, for Carnival of Souls to get me as shook as it did? I had forgotten the long, practically wordless sequence at the end of that film that consists of the protagonist wandering around--and then getting chased through--eerie spaces for almost 15 solid minutes! All the while, the organ score just blares away, and I felt like I could still hear it echoing as I walked through the theater’s empty parking garage alone. So what about you? I know you’re a fan of both films--what felt different about the theatrical experience?

Michael: Well, this isn’t quite essential to the “theatrical” part of the theatrical experience, but it’s always interesting for me to hear what about a movie sticks in people’s memories. The ending of Night of the Living Dead, of course, is peerless and looms large over the rest of the movie upon rewatch--it’s impossible, for example, to view the early televised bits of enthusiastic vigilantism with anything but a pit in the stomach. The ending informs the whole rewatch experience because it’s something of a twist and therefore transforms all the rest of the movie before it. But with Carnival of Souls, that wordless sequence at the end was pretty much my entire memory of the film, so what stood out to me this time was just how much movie there is to that film besides the ending.

In particular, I forgot that the movie actually has characters outside the protagonist and the ghosts that haunt her. But they’re all over the movie’s first half: the folksy gas station attendant, the friendly minister, the folksy landlady (ex: Mrs. Thomas, who really wants you to know that you can shower as often as you like--she doesn’t mind). They’re all played so as to hit this uncanny valley of Midwestern nice, something David Lynch would run with a few decades after Carnival), and they’re both lots of fun and pretty unsettling. I’d forgotten just how much the movie leans on these characters to develop the queasy tone and uneasy relationship to reality that the finale runs with. If the purpose of Night of the Living Dead’s ending is to pull the rug out from the earlier sections of the movie (or at least to allow the viewer to see how little rug there was to begin with), I was struck just how much of Carnival of Souls’s ending was sort of an affirmation of the movie’s first half hour.

Both of those movies were part of Big Ears’s A Sense of Place program, which focused on films with strong attachments to the regions in which they were made. I’m neither from Pittsburg nor Utah, so maybe I’m just pulling this out of the air, but I feel like the connection to region is what makes Carnival of Souls especially fascinating--these characters all feel closely tied to that rural West-Midwest region in a way that doesn’t really come across as strongly in Night of the Living Dead, as much as I love that movie, so the horrors of Carnival feel specific to that region.

Property (1979)

Drugstore Cowboy (1989)

Property (1979) by Penny Allen // Drugstore Cowboy (1989) by Gus Van Sant

Michael: And speaking of region, that reminds me of Property and Drugstore Cowboy, probably the most regionally linked pair of movies at the festival, given that they both take place in Portland, Oregon. Property is a 1979 film written and directed by Penny Allen, and it’s very much in that 1970s mode viewers will already be familiar with from Robert Altman’s movies of that era: a loose, naturalistically filmed movie about a community--in this case, residents of a city block in Portland whose homes have all been put up for sale as the landlord who owns the entire block tries to sell his property. Drugstore Cowboy takes a different view of Portland. Directed and co-written by Gus Van Sant (his second feature, after the hyper-indie Mala Noche), it centers on a band of drug addicts who take to robbing pharmacies to support their habit. I’d not seen either of these movies, so it was exciting to watch them not just for the first time but also in an actual theater.

In fact, seeing Property at all was more of a treat than I’d realized beforehand--it’s Penny Allen’s only feature film, and its distribution is nearly nonexistent; the version shown was, admittedly, not a great transfer (lots of compression artifacts), but apparently that’s the best version available, a copy sent directly from Allen herself to the Big Ears crew. And in a weird way, that rough-and-tumble exclusivity to the movie’s availability feels appropriate to what the movie actually was--so tied to that specific place that it almost makes sense that the movie is only available through hard-to-find objects. It was really cool, and Property ended up being one of my favorite movies of the festival.

Drugstore Cowboy, on the other hand, is of course readily available. Gus Van Sant (Good Will Hunting, My Own Private Idaho) is, fame-wise, just a few notches below American indie household names like Richard Linklater. This is recognizably a Movie movie, if that makes sense, and watching it in a theater felt more like I was tapping into a tradition or joining a crowd as opposed to the intimacy of being one of a relative few number of people who have seen Property. That’s not a slight against the movie, but it did make Drugstore Cowboy feel a little untethered from its “sense of place” in Portland, an effect that makes sense in the context of the movie’s narrative, which involves a lot of travel and vagrancy. Andrew, I know you didn’t get a chance to see Drugstore Cowboy, but how did you feel about Property? Did anything about the movie’s limited availability or regional ties strike you?

Andrew: I thought Property was excellent! As we discussed on the podcast, it presents a really compelling clusterbomb of a dilemma about how conscientious individuals should respond to the increasing corporate takeover of public life (if only Penny Allen was still making movies--Silicon Valley is calling). It’s a topic that could be dreadfully boring, but the colorful and charismatic ensemble make it work. Now, you bring up the availability of festival films: I think this is fascinating to consider. Obviously, at any festival, you can’t see everything, so you have to make hard decisions about what to skip. When making those calls, I weirdly feel more drawn to films with more circulation than I do to obscure gems, even if the festival is my only chance to see them. I think this is because I’ve always thought about film in communal terms--I want to be able to talk to people about movies just as much as I want to watch them. I ended up skipping many of the hard-to-track-down films in the festival (Property excluded) because they just seemed so untethered from film discourse at large.

For some reason, I feel a bigger obligation to see things that friends and critics are talking about just so that I can be a part of that larger conversation. However, I did see most of the 3D program (which had its fair share of under-the-radar titles) just because how much of 3D is an experience that can’t really be replicated without certain settings/conditions/paraphernalia being in place (which you wrote about insightfully in your Stereo Visions piece, by the way), which likely skewed my overall take on the festival’s direction. Even though there are exceptions to my general rule that mostly have to do with my own proclivities--it kills me that The Devils isn’t widely available, for example, and I sought that out at all costs--I still can’t help but feel less-than-thrilled about titles plucked from obscurity when I’m looking at a festival lineup. Maybe I’m revealing a severe shortcoming of my film diet here--am I a bad filmgoer or a bad film critic if I’m less interested in seeking out forgotten gems than I am in being part of the conversation? Does this register as a relatable anxiety about the festival experience for you?

Michael: I do feel that anxiety sometimes. It’s a lot of work to comb through obscure movies for the gems, and it often feels like you’re starting from scratch or eating your cinematic vegetables when you’re watching them. Conversely, it can feel really gratifying to watch movies that you already know hold a place of importance in movie history or contemporary dialogue, almost like you’re joining a club. On my own blog, I’ve done a few projects that involved watching sets of canonical movies, and that was always a lot of fun. On the other hand, I’ve found that it can also be a ton of fun to try to take movies I feel like should be part of that larger discourse about cinematic history and try to wedge it in there. One of my go-tos is Saturday Night Fever, which isn’t “obscure” necessarily but does get kind of misremembered as “that disco movie” instead of, as I think, actually being a great movie deserving a place alongside Mean Streets and all those ’70s grimy depictions of mid-century American urban decay. Long story short, I think one of the things that’s exciting about having seen Property now is that whenever people bring up Altman-style ’70s ensemble movies, I can now throw in a Property recommendation as another essential movie in that history. It makes me retroactively sorry that I didn’t seek out more of those lesser-seen movies at the festival, even though at the time, I was feeling similar to you with the burn-out.

Sixty-Six (2015)

Porcelain Gods (2018)

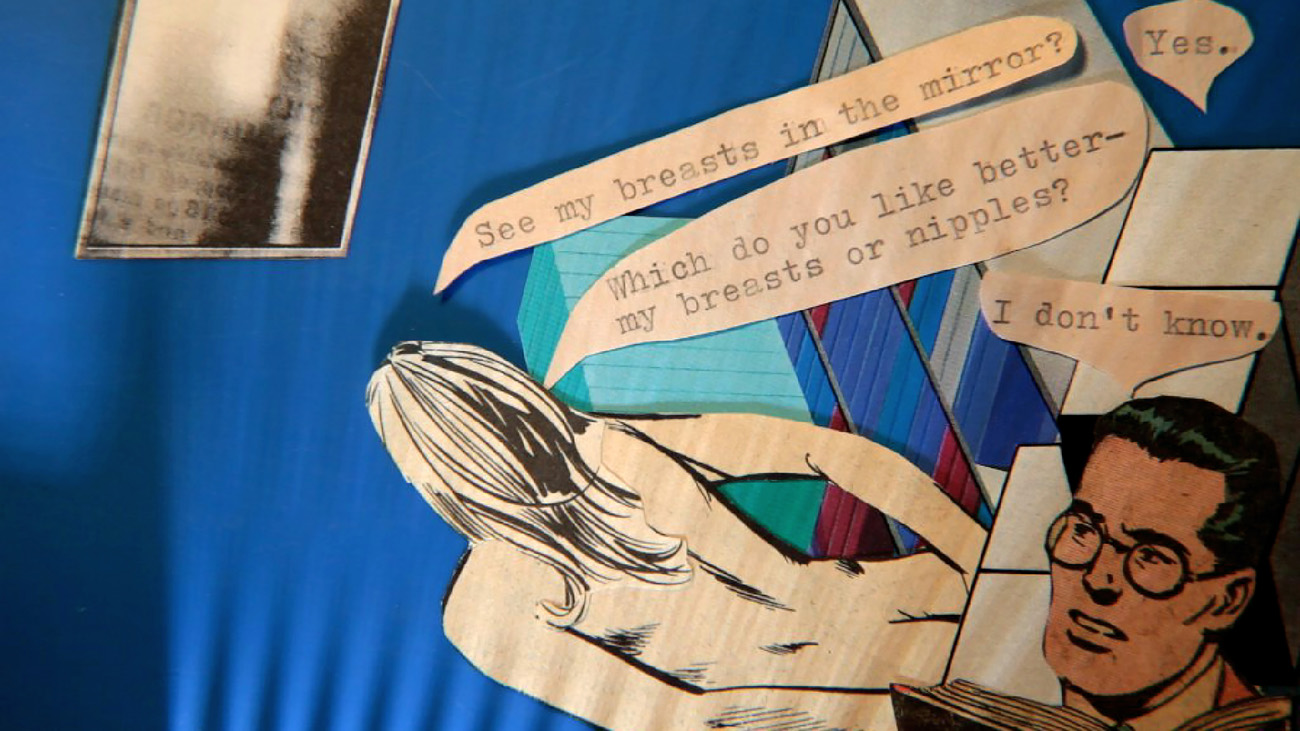

Sixty-Six (2015) by Lewis Klahr // 1,000 Shards of Bliss (2018) by Lewis Klahr

Andrew: Some of the most rare cinema we saw over the course of Big Ears was by Lewis Klahr, who screened a feature (Sixty-Six), a shorts program (which we missed), and an installation cycle (1,000 Shards of Bliss) that presented different shorts depending on the weather! Thanks to the blustery Tennessee Spring, we actually saw the most obscure films of the festival in this installation, since there were certain films he was only willing to show on a rainy day. Lewis Klahr is an experimental animator and a collage artist, who shuffles around clippings from mid-century comic books and newspapers to breathe new life into a pop art design aesthetic that he seems to be mourning thanks to American culture’s long-running obsession with sleek digital surfaces (which goes back to the 90s, I guess?).

I found a lot to enjoy in the shorts we saw from 1,000 Shards of Bliss--specifically how Klahr reappropriates “respectable” iconography from the 60s and makes it sexual. For example, Klahr uses simple stop-motion tricks to make archetypal housewives and secretaries appear to be fellating men in repose--and he does similar tricks to create artificial gay representation with this material as well (there were a lot of clothed men with pasted-on dicks in this program--and the live-action shorts that made their way into this program were similarly explicit). I found this to be pretty genius! There was surely so much lasciviousness from the era of these raw materials that got whitewashed away in artistic/commercial representation.

However, I had a very hard time with Klahr’s feature Sixty-Six. This is a compilation of 12 different short films that are supposedly in dialogue with one another, but they were all so obtuse that I found the experience of watching it very tedious. I expected there to be not characters or plot, but I wasn’t sensing much else either. There’s almost no music, there’s no obvious societal undertone (like there was in the 1,000 Shards of Bliss shorts we saw), and the film speaks in a language so coded that I didn’t even feel compelled to ponder much of anything. It was the biggest lull of the weekend for me. You liked this, though, so you must have been keyed in to something that I missed. What was it?

Michael: First of all, I do agree that 1,000 Shards of Bliss was a lot more fun than Sixty-Six, and unlike Sixty-Six, I actually recognized some of the media reappropriated for the Shards shorts--Jimmy Olsen makes a particularly eyebrow-raising appearance, and I got a kick out of that. But as far as my enjoyment of Sixty-Six goes, I think the key for me unlocking this movie was one of the shorts midway through the movie that involved two of Klahr’s typical comic-book-looking characters arranged in ways that made them look like they were dancing to Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” (Klahr’s music selection was on point throughout his films, though they usually weren’t quite so obvious as this one). It’s a deeply romantic short that leans heavily on the weightless wistfulness of Debussy’s piece, and it probably wouldn’t have struck me as too easy a short if it hadn’t been followed immediately after by a completely silent short comprised entirely of black and white photos of empty furniture. The abrupt, almost smash-cut-like way that the movie transitions to this latter short really hit me, and in that moment, the “Clair de Lune” short became a memory offset by the stark realities of the airless present depicted in the second short, as if something beautiful from the past had been lost. After that, I couldn’t help seeing that melancholy feeling of loss over the rest of the shorts and even the cut-out style of the films themselves.

In the Q&A after the Sixty-Six screening, I asked Klahr about the role of nostalgia in his work, and I think he took this to be criticism (which, in the age of Ready Player One, I suppose I understand). But what I was really getting at (and what he ended up saying) was that I felt in Sixty-Six that idea of capturing the strange, beautiful things that get lost to time as the present marches forward into new technologies and personal experiences. It’s a highly inferential and often static movie, so I get where you’re coming from in being bored (I was bored at times, too). But something about those precise images and sounds also moved me emotionally.

I know one of the things you mentioned when we talked after the screening was that you didn’t always get much out of the way Sixty-Six used found media besides the experience that you were seeing/hearing that original media (I think you said something to the effect of “I liked the Debussy short, too, but mostly just because I like Debussy”). But I also know that you are a fan of sample-heavy hip-hop and electronica, to say nothing of the way that 1,000 Shards of Bliss also re-uses old media. Was the difference between you finding Shards “genius” and Sixty-Six tedious simply due to one boring you and the other not, or do you think these two pieces are using their found media in fundamentally different ways?

Andrew: I think the difference mostly has to do with how much I can make out the intent. As a fan of slow cinema, I’m 100% down with movies that use time (and therefore boredom) as a tool in the same way that you might use color--Jeanne Dielman is probably the gold standard of a movie that is magnificently boring, and I love it. For me, I couldn’t tell what Klahr was trying to accomplish with Sixty-Six while watching it. I can kind of see your interpretation about nostalgia and losing things to time, but the movie didn’t communicate that to me in a way that felt intentional enough. I’ll also say that I really enjoyed Klahr’s Q&A, but anytime the idea of what the film is *doing* came up, it seemed like he wasn’t totally sure either and was content to embrace the nebulousness of it, working by feel. I get the appeal of that from a creative standpoint, but it didn’t work for me as an audience member.

Polyester (1981)

Jackass 3D (2010)

Poyester (1981) by John Waters // Jackass 3D (2010) by Jeff Tremaine

Michael: We’ve been talking about relatively high-brow stuff thus far, but it’s worth mentioning Saturday night, when Big Ears made the inspired choice to make a double feature of two profoundly low-brow mainstays: John “Prince of Puke” Waters’s Polyester and Jeff Tremaine’s Jackass 3D, both of which make a virtue of mind-in-the-gutter filmmaking. We’ve already talked at length about Jackass 3D on the podcast, and I’m sure that readers will be familiar with Johnny Knoxville & Co.’s cascade of extreme physical stunts and scatalogical dares, which Big Ears attendees got to see in all three dimensions (nothing like puke and poop flying right at your face). But it was Polyester that was the real revelation to me. I’m told that Polyester is a tamer John Waters than the Baltimore native’s ’70s output presents, but I wouldn’t know it if I hadn’t been told.

Polyester is a wild, vulgar farce of the American nuclear family starring Waters muse, Divine, as a beleaguered housewife whose family falls apart around her in the most goofily extreme ways imaginable (e.g. her son goes to jail after being outed as the “Baltimore Foot Stomper,” a crazed delinquent who gets off on stomping women’s high-heeled feet). Once I get on this movie’s high-camp wavelength, I found it very funny and a little sad. But maybe even more notable than the content of the movie was its presentation. Back in 1981, the film was released as the first-ever “Odorama” movie, in which the audience would be given scratch-and-sniff cards that onscreen cues would prompt them to use at various points so they, along with Divine’s olfactorily sensitive character, could smell the farts and new car interiors and pizza and whatever else the movie wafted their way. A little bit earlier, you mentioned movie paraphernalia, and Polyester was almost certainly the most unconventional use of paraphernalia in the festival. How did the movie work for you, both as a film in general and also as an experience tied to the “Odorama” gimmick?

Andrew: The Odorama card definitely didn’t feel like an integral part of Polyester to me--I’m very glad Big Ears went out of their way to make the screening special (especially in conjunction with a 3D program that put an emphasis on extrasensory experiences in movie theaters), but I imagine I would have enjoyed the film just as much without it. Part of this is due to the fact that a lot of the scents blended together (with the exception of the new car smell, which definitely popped), but there’s another factor. Paradoxically, I think being given cues throughout the film to scratch/sniff the object in my hand ended up taking me out of the story rather than immersing me in it’s material reality. I guess that’s just inherent to the kind of paraphernalia that Odorama is? 3D glasses give you no choice but to experience their added depth-of-field, automatically and constantly (even if you’re not in a theater, which we much appreciated with regard to the Fireworks glasses), whereas the Odorama card requires looking away from the screen and doing physical labor (however minor) to produce the effect yourself.

But regardless of how effective the smell effects were, I thought Polyester was intermittently hysterical. I especially enjoyed the plot line of the son as the town’s notorious foot-stomper (and I LOVE that he is referred to as such on the evening news), as well as the sister’s constant dancing, even when trying to open and drink sodas. There are a lot of small details that got me, too--like the scene where Divine’s character is, out of nowhere, feeding horses with her new beau, or when we find out that he runs an art house cinema (in which an advertisement invites us to “ponder the intellectual meaning of cinema!”) that’s actually a front for a cocaine ring? When the film was working in that sweet spot of high-camp absurdity (which usually involves music and montage), I found it immensely enjoyable. What worked a little less so for me were the actual character beats of Divine’s protagonist. She’s crucially a drunk, and although I get the idea that the movie is lampooning tropes of mid-century melodramas involving frustrated housewives (it reminds me a bit of that St. Vincent song, “Pills”), long sequences of Polyester involve watching her falling over furniture while tearfully moaning. I go back and forth between considering it fatiguing (when I’m feeling generous) or sadistic (when I’m not), but either way--it was a little much for me.

And speaking of things that are a little much, let’s return to Jackass 3D for a moment--specifically the experience of watching it with a crowd. Apparently, we are the only people in the damn world who don’t get hype out of their minds for this stuff. Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised at the multitudes contained within the kind of audience that nods bookishly through avant-garde features, but I really wasn’t expecting the Big Ears crowd to lean into Jackass quite as hard as a it did. The movie was working for them before it even started--people were howling as soon as the studio logo came up! (And I don’t mean Johnny Knoxville’s Dickhouse studio--which, of course it’s named that--I mean the totally unremarkable MTV Studios astronaut logo.) Although I did appreciate how sharp all of the 3D effects looked in this (it gained a half-star on Letterboxd from me for that alone), I felt even more alienated from the film after seeing just how much it was working for other people on a visceral level. Were you similarly surprised by the response to this? Do you have any explanation for it?

Michael: I think I would have been surprised if the podcast hadn’t already exposed me to the world of cinephile appreciation for Jackass. With the MTV Studios logo, I have to assume that a lot of that has to do with the familiarity of it and maybe the anticipation of reliving past experiences--I think about the way my stomach still kind of thrills when I see the 20th Century Fox searchlights and fanfare followed by the Lucasfilm logo, even though my days of Star Wars obsession are mostly in the past (even a few years into this Disney Star Wars thing, it still feels wrong not to have that fanfare before “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…”). As for the rest of the movie, I do feel mostly locked out of the experience of enjoying it on the rolling-on-the-floor-laughing level that a lot of our Big Ears peers seemed to feel the movie on, though in the context of a film festival that was often aggressively experimental in the ways it used 3D effects, it was a kind of release to see 3D used so straightforwardly and so spectacularly. And maybe that’s another aspect to it--Big Ears’s film program isn’t without its traditional narrative offerings (we’ve already talked about several of them, and we’re about to talk about another one), but it is definitely a festival also calibrated to expose viewers to a lot more challenging material than they would normally encounter on a regular basis; perhaps Jackass (and Polyester before it) is a release after the avant-garde. I can imagine a movie as relentlessly surface-level and physical and silly as Jackass 3D being a nice palate cleanser after having stroked one’s chin meditatively to, for example, Sixty-Six. I mean, I still didn’t like it, but I can see it being appealing as an occasion for people to let their hair down a little.

Dial M For Murder (1954)

Olympiad (1971)

Dial M For Murder (1954) by Alfred Hitchcock // CHROMA_DEPTH Shorts Program

Andrew: Maybe Johnny Knoxville would be proud of this segway: let’s transition from Dickhouse to Hitchcock. I had never seen Dial M For Murder before! And I’m glad I hadn’t--apparently this has almost never played in 3D aside from it’s very first few theatrical screenings (before the studio declared the 3D gimmick unsuccessful and pulled it). And although Hitchcock doesn’t exactly go HAM on the 3D elements in the same way that the Jackass bros do, there is precisely one three-dimensional moment that I can’t imagine the film working in the same way without. When Grace Kelly is being murdered, she reaches out for the telephone, and her hand comes right out of the screen towards the viewer. It is an astonishing moment, perhaps even more so because of how low-key the effects had been leading up to that point. Filmmaker and festival programmer Blake Williams (more on him later) contextualized this scene within the broader arc of Hitchcock’s career, which over and over again explores the voyeuristic nature of the relationship between audiences and actors. In some cases, we’re made to feel complicit in violence against them, in others, we’re meant to question the pleasure we get out of peeking into other people’s lives--in this case, we’re being literally reached out to for help, but we’re powerless to do anything.

Unfortunately, I think the film peaks there (before the halfway point) and fizzles out slowly, despite how delightful the facial expressions and mustache contortions of John Williams (not that one) are throughout. When Hitch tries to pull off a 3D stunt in the film’s latter half that mirrors the first one, I couldn’t help but feel let down--it pales in comparison to what he already did. However, I know that you’re less interested in all that than you are in the more understated ways Hitchcock uses 3D in this film--and I specifically wanted to ask you about that in relation to the CHROMA_DEPTH 3D program, which emphasized color 3D images that subtly play with your depth perception. What’s your take on what Hitchcock is doing with color and depth in Dial M For Murder--and, as someone who had seen the movie in 2D earlier in life, do you think it works just as well without that stuff?

Michael: I think the movie absolutely works better in 3D. Without 3D, Dial M is still very fun but also feels like a transitional work for Hitch as he moved from the more traditional narratives of his British and early Hollywood days (e.g. Notorious, Shadow of a Doubt) into the more radical works of his next decade (particularly Vertigo and Psycho, which share Dial M’s bifurcated narrative structure and whiplash-inducing tonal/genre shifts). The 3D adds a lot of formal richness. It’s a little gimmicky--the 3D elements of the movie seem entirely built around the Wow moments you mention, Hitchcock underplaying the 3D until those two moments, when he allows it to pop out all at once--but it’s undeniably effective. It also does a good job of highlighting the value of a Hollywood set and the control that it allows a director. Most of the movie is set in controlled, interior spaces and I was struck by just how effectively the 3D framed those spaces (and just how much the 3D fell apart when the movie used rear projection to create the illusion of the outdoors). In a movie that’s so obsessed with the ways that human beings move through three dimensions--there are multiple extended sequences of characters walking through the apartment and narrating their movement as they try to predict or retrace how someone else would have moved through that same space. 3D gave me an intuitive understanding of that set in a way that 2D never did, and I thought that was pretty neat.

Another showing that seemed to have a similar intention of wowing audiences with pure 3D spectacle was CHROMA_DEPTH, a set of experimental 3D shorts from a variety of filmmakers both old and new. Obviously, being experimental, the CHROMA_DEPTH shorts don’t have a lot narratively in common with Hitchcock’s work, but they do share a propensity for pure fun in the cinematic medium, and I appreciated how much Big Ears ran with the playful nature of the shorts, giving us three different sets of 3D glasses to play with as we watched these shorts. Also relevant to Hitchcock is the fact that two of the shorts didn’t even require glasses at all, which feels like an interesting connection to the way that we can view Dial M for Murder in both dimensions. I know we both enjoyed the “Fireworks” glasses short (Jodie Mack’s jubilant Let Your Light Shine), but I’m curious what other shorts of the bunch stood out to you and how you felt about the switching out of glasses in the event and even the not needing to use glasses at all at some points.

Andrew: As I wrote about in my piece for Arts Knoxville, one of the biggest discoveries of the fest for me was the work of Lilian Schwartz, who had two shorts in the CHROMA_DEPTH program. Schwartz made abstract animated films using her expertise as an early computer programmer (a lot of people don’t realize that programming was “women’s work” before video games got dudes obsessed; a lot of pioneers of electronic music were women, too, and that same proto-Kraftwerk aesthetic runs throughout Schwartz’s work). These shorts are pure eye (and ear) candy, and are consistently engaging in their colorful glitchiness despite basically being formal exercises in coding. Schwartz apparently “discovered” her films were in 3D about a decade after making them with the release of the ChromaDepth glasses--which make “hot” colors (red, orange, yellow) appear as if they’re advancing towards you while “cool” colors (blue, green, purple) appear to recede. Because Schwartz is fluctuating the color pallete of her shorts constantly, it makes for a pretty disorienting experience--but I also saw a connection Hitchcock in how much Dial M For Murder seems concerned with *orienting* you--placing certain objects in the foreground while others are relegated to the background and the characters move about in the liminal space in between. 3D has a great capacity to just create more space on screen in addition to popping out of it every so often.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010)

Ulysses in the Subway (2017)

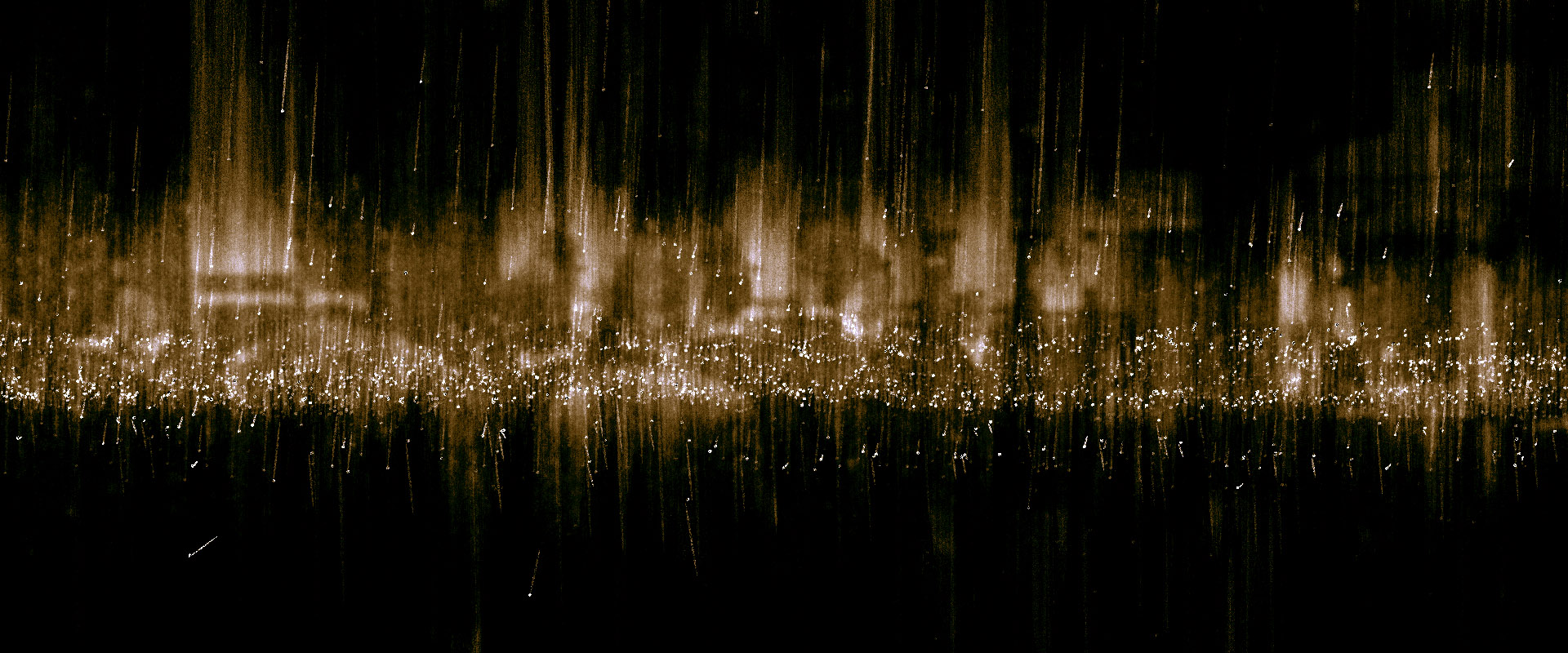

Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) by Werner Herzog // Ulysses in the Subway (2017) by Ken Jacobs, Flo Jacobs, Marc Downie, and Paul Kaiser

Michael: Backpedaling a little bit to my earlier comments about how Hitchcock uses 3D to define indoor spaces, another interesting pair along that vein for me was Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams and Ken and Flo Jacobs’ Ulysses in the Subway. Both are documentary features of sorts about interior spaces. Herzog’s is mostly traditional (it was produced by the History Channel), using 3D cameras to depict the Chauvet Cave in France, where in the 1990s scientists discovered what they eventually realized were the oldest known human-made paintings. Ulysses in the Subway is a much different sort of movie; it takes 3D to the extremes of abstraction by using a computer algorithm to transform an audio recording of co-director Ken Jacobs’s subway ride home into a 3D waveform--the entire movie is this waveform, accompanied by the audio itself. They of course use their spaces to much different ends. Forgotten Dreams, on the one hand, seeks to familiarize us with an alien world (the distant prehistory of the human species) by presenting as photorealistic a depiction of the cave as is possible with modern technology, while Ulysses takes a setting that many Americans are intimately familiar with (the New York City subway) and makes it strange and unfamiliar in ways that are often awe-inspiring--a few moments legitimately evoked the feeling of the Stargate sequence in 2001, but in 3D, which is maybe even more viscerally awe-inspiring than Kubrick/Clarke’s merely two-dimensional vision.

I found both to similarly mesmerizing experiences (though I’d seen Forgotten Dreams already), as different as their goals seemed to be. It may seem silly to compare these two movies like this, but I know that you were much more taken by Ulysses in the Subway than with Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Can you walk through why that was?

Andrew: It’s a strange case: Cave certainly had a lot more stimulus to keep you interested throughout the film as opposed to Ulysses’s single audiovisual element, yet I only ever felt bored in the former. I think the main difference is that Herzog’s documentaries are very sporadically structured--he takes you on a nonlinear exploration of the cave, veering off into disconnected tangents that are driven by his own ponderings on human evolution as well as experts presenting their research about the cave itself. The former is profoundly more compelling--especially Herzog’s speech about how alligators may evolve past humans in the film’s epilogue. And while I definitely think the work that the experts are doing is important (and that having a certain amount of scientific exposition is necessary for the movie’s speculative side to work), your mileage varies throughout the film based on how interested you are in what data points are being explained to you by talking heads--it’s very much a History Channel documentary in that way, despite Herzog’s philosophical bent and the movie’s visual complexity. One research-driven scene in particular worked really well for me due to how integrated it was to the visuals: the explanation of how every detail of the cave is mapped digitally, which leads to a fully digital sequence (see image above) where an imaginary camera glides through millions of points on a three-dimensional grid. Other sections were far less visually engrossing, which led to the movie feeling meandering and long, even with its very short runtime of 95 minutes.

Ulysses in the Subway, on the other hand, doesn’t outstay its welcome (59 minutes!) and presents itself to you on a practically molecular level: we know what an ordinary subway sounds like, but here’s what that sound looks like. The negative way of characterizing it is as a one-trick pony, but I found the trick utterly captivating. The way that the digital artifacts of the audio file work together with the 3D glasses turn the subway’s cacophony of sound into this incandescent starfield that imbues this mundane task (taking the train home) with cosmic beauty. And when certain noises break through the din, what an immersive trip the waveform becomes! It’s like being sucked into a black hole, or, to use your completely correct comparison, 2001’s Stargate sequence. The trailer calls this “an everyday epic,” and I think that this makes total sense with the title--referring both to the mythological figure of Homer’s Odyssey, but also Joyce’s own everyday epic that charts a 24-hour period in famously transcendent fashion. In short, I think that Ulysses in the Subway is confident and focused in what it wants to do with its single location--and I found what it wants to do totally transfixing. Herzog’s spelunking session seems a little waffly by comparison.

Prototype (2017)

Speechless (2008)

Prototype (2017) by Blake Williams // EXTRA_TERRESTRIAL Shorts Program

Andrew: Let’s talk about a few more avant-garde explorations of earthly spaces: the EXTRA_TERRESTRIAL Shorts program and Prototype by Blake Williams, who curated much of the Stereo Visions 3D program. Both of them seem similarly concerned with taking spaces and objects we’re familiar with and making them strange again. EXTRA_TERRESTRIAL was composed of avant-garde shorts meant to warp our understanding of things like roundabouts, concrete, and--controversially--the vulva. Prototype is a lot more interested in natural phenomena than it is in surfaces, as it invites us to experience the historic Galveston hurricane through a glass darkly and in three full dimensions. Prototype was the opening film of the festival, and we’ve both talked about it a lot already--on the podcast, in your Stereo Visions piece, and in my review for Arts Knoxville--but I’m wondering if your perspective on it has shifted at all in relation to all these other films (especially the 3D ones). Blake Williams is a 3D scholar, so how does your own experience learning to love the third dimension affect the way you see this film? I’m also dying to know what you thought of the 13-minute 3D vulva short, by the way.

Michael: I’m afraid I don’t have much clitical--I mean critical commentary on Speechless, which I found kind of audacious in theory but boring in practice. As for Prototype, one of the things that helped my appreciation for it grow as the festival went on (though I never ended up liking it as much as you did) was realizing just how unique its ambition is relative to most of the other 3D films we saw. What I learned about 3D from this festival is that 3D (or at least the 3D curated for this weekend) often involves films that explore a single idea to the nth iteration--for example, A to A, Johann Lurf’s short from the EXTRA_TERRESTRIAL showing that consists entirely of footage of cars navigating roundabouts. There’s nothing wrong with movies like this (though it perhaps inevitably leads down the road that takes us to 3D genitalia), but it is a particularly focused and narrow method of filmmaking. Prototype, by contrast, is practically an epic: a multi-part feature that evokes both the sweep of history and the inscrutability of metaphysics, along with sections of pure abstraction. I don’t think we saw anything quite like it in the festival; Cave of Forgotten Dreams seems the closest in terms of scope and awed relationship to human history, but whereas Herzog’s film is a more or less traditional documentary, Prototype is notable for just how out there it is, stylistically, and it doesn’t seem much of a stretch to say that there are images in that movie unlike anything I’ve ever seen in a cinema. I wasn’t ever completely on its wavelength--and in fact, I enjoyed some of the single-minded 3D films much more (the two Norman McClaren shorts that screened in the EXTRA_TERRESTRIAL show, for example, which were delightful and playful and vibrant). But it was a commanding and impressive vision and definitely a strong selection to open the festival.

Goodbye to Language (2014)

Twelve Tales Told (2014)

Goodbye to Language (2014) by Jean-Luc Godard // STRETCH_FOLD Shorts Program

Michael: And now that I’ve mentioned “commanding and impressive visions,” I suppose it’s time we get to the heavy hitter: Jean-Luc Godard’s Goodbye to Language. Along with Dial M for Murder, Goodbye to Language was probably the biggest 3D title in the Big Ears lineup--a major film by a major filmmaker that audiences are unlikely to encounter elsewhere in its intended three-dimensional format. This was one of my most-anticipated movies of the festival; I remember the movie coming out several years ago and being frustrated that I was basically cut off from one of the most critically acclaimed movies of the year (despite its appearance on Netflix streaming) because of its format, so this was something of a culmination of a quest for me--even more so after you and I decided to bone up on our Godard background and binged four of his earlier films in preparation for this screening. We’ve talked about Goodbye to Language in the podcast already, but one of the things that stood out to me about the movie was its sense of play. For a movie that feels like the culmination of Godard’s decades-long middle finger to Western civilization, Goodbye to Language is also surprisingly whimsical. Long sections of the movie are devoted to a dog just doing charmingly doggish things like rolling in the grass and frolicking in a lake. Other times, Godard seems to be intoxicated with playing around with his new movie toys, like the memorable instances in which he exploits 3D to follow two characters in the same shot. And then there’s the recurring appearance of poop throughout the film, a motif Johnny Knoxville would be proud of.

Godard’s not the only one fooling around either; the entire festival was filled with movies that seem like the result of somebody goofing off with their movie equipment. The STRETCH_FOLD shorts screening was no exception, and it included one of my favorite instances of play in the entire festival--Twelve Tales Told, a short that is the result of twelve famous studio intros smooshed together. The other shorts of STRETCH_FOLD are maybe a little more conceptual (more than everything, for example, is basically 13 minutes of 3D static), but they all feel of a piece with Godard in that they are--at least in part--excuses to indulge in a whimsical curiosity of the “Dude, what do you think will happen if…” variety. We’ve talked about a lot of serious, capital-A Art stuff here, but I sometimes feel like what people might call “pretentious” about art films can also just as easily be called “playful.” So maybe this is a good way to bring our conversation to a close: what were your favorite moments of play in Goodbye to Language, STRETCH_FOLD, or the festival as a whole, and how did that fun-oriented experimentation work for you?

Andrew: I think that playfulness is a good note to go out on. In a sense, something like Night of the Living Dead could be seen as a more difficult movie because of how concerned it is with challenging common assumptions about America (that we’re a nation of law and order, for instance--and that the law is impartial). Something like Goodbye to Language, on the other hand, doesn’t even really ask you to get it because of how much you can appreciate the film’s sense of play as an end unto itself. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, I think that playfulness on the part of the dog is of central importance: Godard seems interested in warping our sense of color, space, and language comprehension to the point that we begin to see the world from a more animalistic perspective--which is inherently more innocent and playful. And as somebody who’s attended every Big Ears festival since they were revived in 2014, that’s the mindset that I’d recommend people bring to the festival (and this goes for music too). You may not recognize every name on the lineup and you may not like everything you attend, but if you have an open mind (something something big something something ears), you’re inevitably going to find stuff that is just delightful and/or moving on some non-verbal, instinctual level.

(Appreciate things on a non-verbal level, he says, 7,000+ words in…)

Thanks for reading!