Review by Andrew Swafford

A LONG PREAMBLE ABOUT THE PROBABLY-UNINTENDED IMPLICATIONS OF JOHN KRASINSKI’S PHRASING WHEN TALKING ABOUT HORROR FILMS, INCLUDING HIS OWN

After A Quiet Place premiered earlier this year at South by Southwest Film Festival, John Krasinski took to the stage to give some background on how he, smug everyman from The Office, came to make a horror film. In his talk, Krasinski admitted to being a “late to the party” horror fan, only recently becoming interested in the genre through movies like Get Out (2017), The Witch (2016), Don’t Breathe (2016), and The Babadook (2014). In other interviews, he additionally cites the only-slightly-older Let the Right One In (2008), but you get the idea.

John Krasinski referred to these as “elevated horror movies,” which is in keeping with what some journalists and critics have called “highbrow horror” and what others have even called “post-horror” (though the less said about that label, the better). Whatever you call it, this crop of genre fare consists of movies that forgo extreme violence and jump scares in favor of character development, atmosphere, and allegory. Jade Budowski of Decider emphasizes this last part: “‘Metaphors’ may sound yawn-inducing, but hear me out: wouldn’t you rather be scared by something, and then be pleasantly surprised to discover something of substance lurking beneath the surface?” Let's put her questionable point about metaphors being yawn-inducing aside; if we are to take Get Out and The Babadook as model examples of the (sub)genre, then she’s right--they live and die on their central allegories, around which all their film mechanics are meticulously constructed.

Now, I unequivocally love almost all the films cited by Krasinski as influences. But there are some real problems with this idea of “elevated horror” worth getting into before going into specifics on A Quiet Place. It’s a condescending phrase, and though common practice suggests otherwise, we can praise horror films we like without being condescending towards the genre as a whole. Here are my three truths:

- Firstly, horror movies have always had substance. To paraphrase former Cinematary guest Sydney Taylor, A24 didn’t invent the thoughtful horror movie. Honestly, I feel insulted even defending the idea that the horror movies of yesteryear did, in fact, mean something (*proceeds to do it anyway, sighing*), as you’ll be hard pressed to find a more thematically-dense genre in cinema than horror. In the 40s through the 60s alone, horror gave us gothic romances about men playing god and monster movies about atomic trauma and zombie drive-in features about the dissolution of American society, just to name a few of the obvious ones.

- Secondly, it is ignorant and elitist to assume that because a movie is violent it must not be smart. Y’all have seen Texas Chain Saw Massacre, right? How about that for a movie with a lot on it’s mind! Entire books have been written on the subject of hyperviolent slashers that explore challenging topics like sexual violence and gender fluidity--and even the most extreme of modern horror films like Funny Games and Martyrs are rife with metafictional subtext about what it means to experience violence through a cinematic filter, explored in much the same way that Hitchcock and Cronenburg did in decades past.

- Thirdly, “elevated horror” can easily be lazy posturing. When an entire subgenre is not so much defined as what happens in the films as it is defined by what doesn’t (I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard people compliment a horror film by saying “and there aren’t any jumpscares!”) then eventually it becomes a game of who can do the least heavy lifting. I pray that this trend has already reached its nadir, as last year’s It Comes At Night just about starved me to death for lack of...substance? plot? scares? anything? A man cannot live on ambiguity alone.

I have no desire to “own” John Krasinski here (as he probably doesn’t intend any of the implications of his phrasing) or to assume that just because he’s new to the horror game that he lacks the knowledge necessary to make a good film (and dear lord do I not want to resuscitate that recent Twitter feud about whether or not critics need to know film history). On the contrary! A fresh perspective could be exactly what the genre needs right now! But I think that pointing out flaws in modern horror discourse is important groundwork to lay out, considering Krasinski parrots a lot of the common talking points: the most obvious one being how often Krasinski insists that he “never saw it as a horror movie” while writing A Quiet Place. Just imagine my Jim Halpert face right now.

Regardless, I’m fascinated by the fact that A Quiet Place is maybe the first ever mainstream horror film created by someone whose appreciation for the genre is informed almost exclusively by horror from the last few years--the new wave of “elevated horror,” to use Krasinski’s unfortunate phrasing. And unfortunate as it may be, I’m going to use that phrasing anyway, in order to compare Krasinski’s film to the rest of the wave he’s admittedly riding. With these specific movies in mind, how does their influence play out in the film?

THE ACTUAL REVIEW PART 1: VISUAL STORYTELLING

A Quiet Place opens in much the same way as several of its “elevated horror” contemporaries: with a brief, standalone prologue that demonstrates how the the rest of the film will operate. The opening of It Follows, for example, offers its audience an unnamed suburban girl running from an uncertain threat--the centrally-placed camera rotating a clean 360-degrees to let us know that the object of her fear (and therefore our fear) could come from any direction. The first scene of Get Out, similarly, illustrates the discomfort of white neighborhoods for black citizens, using an unbroken tracking shot to follow a lost man into his unexpected abduction. Both examples concisely express the films’ primary concerns, both physical and thematic. A Quiet Place follows this formula as well.

In Krasinski’s film, the opening scene takes place months before the rest of the narrative and follows a family scavenging for medicine and other supplies in an empty and already-ravaged grocery store. They do this silently, and close attention is paid to the characters bare feet in low-angle shots as they move with great trepidation, clearly in fear of making noise. There is no soundtrack, and dialogue is always delivered in low whispers or subtitled sign-language. As soon as the silence is broken, a monster jumps through the frame, killing the offender--paired with a non-diegetic volume blast for good measure.

There are a few key things working here. The set design implies a broader post-apocalyptic society that doesn’t need further explanation, the physical acting implies the scare mechanic’s singular rule even before it is broken, and the sustained silence of the film itself crucially teaches the audience how to watch: very quietly. Even the most minor theater noises--phone vibrations, popcorn crunching--break the film’s immersiveness, leading to countless unoriginal joke reviews lamenting theater patrons (sometimes themselves) who make even the slightest noise. (It’s the “I just got out of Lady Bird and called my mom crying” of 2018 film discourse. Not to say it isn’t genuine! But y’all, you’re allowed to have different takes, you know.) A Quiet Place isn’t the first “elevated horror” film to play with the idea of characters who must stay silent to stay alive--that would be Krasinski’s cited inspiration Don’t Breathe, which I reviewed--but for the most part, Krasinski stays truer to the spirit of the concept here.

It Comes At Night

A Quiet Place

After the opening sequence of A Quiet Place, the audience knows everything they need to know for a story set in this universe to play out. Inexplicably, though, the film then proceeds to telegraph this same exposition again and again and again. These next scenes are still and dimly lit, much like the aforementioned It Comes at Night, which I reviewed--and like that film, it wastes a lot of time before evolving beyond its initial conceit. There are a few important character details revealed in A Quiet Place’s first act, of course (Emily Blunt’s character is pregnant, for example, and her stomach is a ticking time bomb in this world), but moreso than anything else, every passing minute seems to communicate the same basic piece of information (“these people have to be quiet”) as if it is always being revealed for the first time.

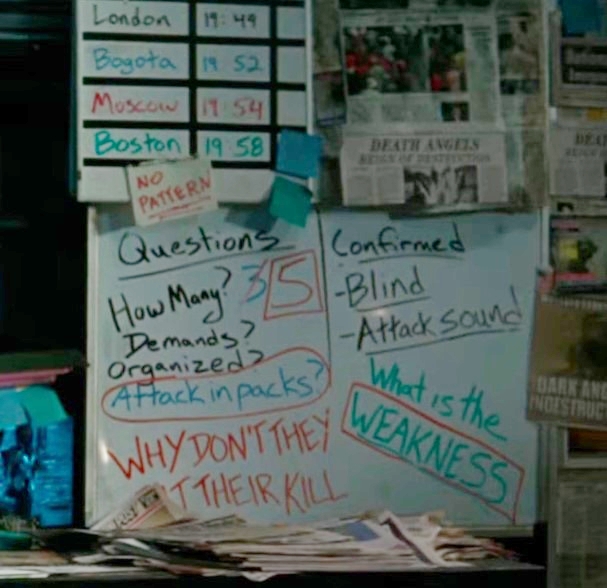

John Krasinski has created a cinematic challenge for himself: he can’t use dialogue (or at least not much of it), so he needs to communicate with his audience visually. It’s a shame that, often, that visual storytelling equates to letting his camera pan over a whiteboard that spells out exactly what we already know: there are monsters; they attack sound; their weakness is unknown. In the opening sequence, Krasinski clearly respects his audience’s capacity to be quiet, patient, and intelligent, so I’m not sure why he follows that up by insulting that intelligence immediately afterwards. He has the audience warmed up for some visual storytelling, but there’s not much story to be told.

THE ACTUAL REVIEW PART 2: TENSION

The film starts to move when its rules are being broken rather than followed. Upon breaking them, of course, A Quiet Place becomes a lizard-brained game of hide-and-seek between predators and prey, in which characters don’t matter so much as their physical placement in relation to one another--and more importantly, the movie’s monsters, whose abilities of heightened perception are communicated through their spiral eardrum design. The characters played by John Krasinski, Emily Blunt, and Millicent Simmonds must be strategic and use all their tools in order to evade the creatures, and the film world becomes a mechanical contraption of smoke signals, weaponized fireworks, Christmas lights, sand paths, grain silos, concealed rooms, artificial respirators, and of course, shotguns--these are the structural systems necessary for defense in a hostile world no longer protected by those of industrialized civilization (if you’re now imagining the film as a conservative-doomsday-prepper-fantasy, you’re not far off--more on this later).

Unfortunately for the characters, the material world works against them in unexpected ways as well, one of which I found terribly unfair: an exposed nail appears on a staircase early on, and a Hitchcockian close-up promises a scream-inducing pierced foot later (Krasinski has cited Hitchcock--along with Alien--as one of his few classic inspirations). This would be fine with me if it were not for the fact that Emily Blunt’s character definitely sees the nail and in any rational universe would have protected herself against it before rushing off. The script, however, doesn’t allow her that choice, and the gratuitous pain is excruciating.

The nail thing is a personal gripe, I suppose (I’m even a lightweight when it comes to needles used for medical purposes, so body-puncturing scares are a tough sell for me). More pressing than the mechanics of the house is the way that the mechanics of the film operate at critical scare moments. The largest issue here is the widespread presence of jump scares, which “elevated horror” purists seem to consider contemporary horror’s cardinal sin. BBC critic and horror aficionado Mark Kermode refers to the phenomenon of omnipresent jump scares “cattle prod cinema” and decries the mechanic as altogether lazy. I’m less harsh on this: jump scares can be both effective and creative, as demonstrated in that one goosebump-inducing moment from Under the Skin. In the case of A Quiet Place, there are very few scares in it that don’t qualify as jump scares (one of the exceptions--taking place inside a grain silo--is pretty harrowing). The ubiquity of jump scares is partially a result of the very nature of the film’s premise--unexpected noises have deadly consequences. However, the film goes wrong in one ironic respect: sound.

Since the film trains the audience early on to always be scared by unexpected noises, then the noises themselves have the potential to be scary enough without non-diegetic stingers, which Krasinski deploys like artillery all too frequently. A Quiet Place in this way undercuts the exact thing than makes it unique, continually pulling out the same tired trick of “quiet quiet quiet BANG” (to again borrow Kermode’s language) that “elevated horror” is supposedly transcending.

There is also Krasinski’s repeated usage of the false scare--a tension-deflating move that Chris Stuckmann explains well here--of which the shower scare ends up being one of many examples. Perhaps the silliest false scare in A Quiet Place involves raccoons (who are quickly eaten by the film’s real threat), but the most offensive one takes place in the film’s much-marketed bathroom set. At one point, a character thinks they are alone in the bathroom until a hand is placed on the shower door behind him--a moment that could be terrifying in an understated way if it weren’t for the unnecessary shriek of the film’s intrusive score.

One could argue that Krasinski’s approach heightens the experience by making the quiet parts of the “quiet quiet quiet BANG” equation extra quiet, but even taking dynamic range into consideration, it comes across like nails on a chalkboard to me.

THE ACTUAL REVIEW PART 3: CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT + INTENDED ALLEGORY

Maybe Krasinski would take issue with all this scrutinizing of the film’s scare tactics, because, as he explains, the movie’s main goal is more on the emotional side. In Krasinski’s own words: “as much as I love hearing people say this movie is scary, for me this movie is as much about family...Even when I did my rewrite of the movie, I just drilled down even more on that metaphor of parenthood, what extremes would you go to to protect your kids." So there it is--the central allegory at the heart of the film that makes it more than “just” a horror film (something something whatever that means something something see tirade above). Here it’s worth pointing out (as it commonly is) that Krasinski stars opposite his real-world wife, Emily Blunt, which is meant to bring a sense of authenticity and emotional resonance to a story about a husband and wife raising two kids, still processing grief for a third, and expecting another--especially in a world where their childlike behavior as natural as crying can have such deadly consequences. However...this allegory doesn’t work for me, both on the level of its intended implications and its unintended ones.

As far as the allegory’s intended effect goes: it’s just so thin. I’ve read a lot of interviews with Krasinski about this, and he always says the same basic thing--A Quiet Place is about how far you would go to protect your family. That is just vague enough to feel important but not really resonate on an emotional level due to how little these characters are fleshed out. All the characters are two-dimensional, perhaps due to the neanderthal-like return to nature that the post-apocalypse pushes them into (and the patriarchal gender roles that come along with that): Krasinski is a hunter and craftsman, Blunt is a nurturing mother and birth-giver, and the kids are mostly devoid of roles and personality, existing to be saved in order to fulfill Krasinski’s parental hero narrative. It’s entirely possible that Krasinski is banking on a general audience walking in with an automatic investment in he and Blunt’s celebrity coupling, which I just don’t have--but even if this is the case, it’s his job as actor/director to get me invested, and I never felt that tug.

There is an interesting conflict here, though, between Krasinski’s character and the one played by Millicent Simmonds, who thinks that her father blames and resents her for her brother’s untimely death. This could potentially serve as a really heavy emotional core, but it doesn’t quite have weight. First of all, on a story level, Krasinski’s character doesn’t resent his daughter at all--this is all just childhood insecurity and miscommunication--so Krasinski plays everything too straight for things to feel tense. Simmonds, on the other hand, brings a reserved sadness to all of her scenes in the film (she’s certainly its strongest acting talent), and you feel connected to her immediately--but the tension between her and Krasinski is never truly dramatized. They share very little one-on-one screen time, their conversation is forced to be minimal due to the movie’s central conceit, and that insecurity that Simmonds has been harboring is only ever communicated because it is explained to us directly by another child in one of the film’s only dialogue-heavy scenes. Again, in a movie that forces visual storytelling, Krasinski opts to tell rather than show.

Noah Wiseman in The Babadook

I’d like to compare this to what is unequivocally the best allegory of parental anxiety within the “elevated horror” genre: The Babadook, which Krasinski cites every time he is asked about his influences. Even if there was no monster in that movie (and oh there is), the mother-son relationship would still be horrifying. It’s about a single working mother whose already exhausting life is completely subsumed by having to take care of her emotionally disturbed 6-year-old son, who plays with homemade weapons and gets in trouble and school and has nightmares and sees monsters and never runs out of energy. The dynamic works because you empathize with the mother on many levels: she’s worn down by her son, she’s scared of her son, but she also loves him sincerely, knowing that most of this hard-to-manage behavior is the manifestation of unprocessed grief for his dead father. That tension between caring deeply for a child and being downright angry with them constantly is the most powerful (and relatable) part of The Babadook as a whole. It helps that both performances--Essie Davis as the mother and Noah Wiseman as her son--are both beautifully expressive, raw, and human.

It perhaps goes without saying that A Quiet Place doesn’t reach these heights. As with most things, part of this is due to the conceit--The Babadook is a boisterous movie, and A Quiet Place can’t quite go there by design. But comparing the mother/son dynamic in Babadook to the father/daughter dynamic in Quiet Place really goes to show just how thinly Krasinski's characters are sketched and how underwritten their relationship is.

And as far as “sacrifice” for children goes, A Quiet Place really just offers a symbolic one, in which Krasinski’s character offers a grand gesture of sacrifice in the film’s climactic moment rather than representing anything that resembles the small, petty sacrifices that parents make for children all the time (watching the Minions movie, for instance, to use a real-life example from a previously-cited critic). This is not to say that more archetypal parent/child relationships can’t have resonance, though! Another post-apocalypse parent/child story in this vein I’m reminded of is The Road, from fellow Tennessean Cormac McCarthy--but Krasinski never writes a line with one-tenth of the power of “If he is not the word of God God never spoke." The best Krasinski can do is “I love you. I have always loved you.” Which, like most of the parent/child stuff here, is just a little...basic.

THE ACTUAL REVIEW PART 4: UNINTENDED (?) ALLEGORY A.K.A. LIBERAL SNOWFLAKE SHIT

There’s also the matter of the allegory’s unintended implications. Unlike some of my fellow Cinematarians, I think that allegory is a totally valid form of storytelling, no matter how obviously it may be telegraphed--thematic clarity is something that I think audiences really benefit from (I feel this especially so as someone who teaches teenagers how to interpret stories professionally). However, allegories are tricky--they can take on totally adverse interpretations if they aren’t written sharply enough, and it can be very easy to project one’s own ideology onto a vaguely-written allegorical story. Matt Zoller Seitz’s review of Zootopia points this out concisely when he writes, “I can imagine an anti-racist and a racist coming out of this film, each thinking it validated their sense of how the world works.” A Quiet Place certainly has that problem as well.

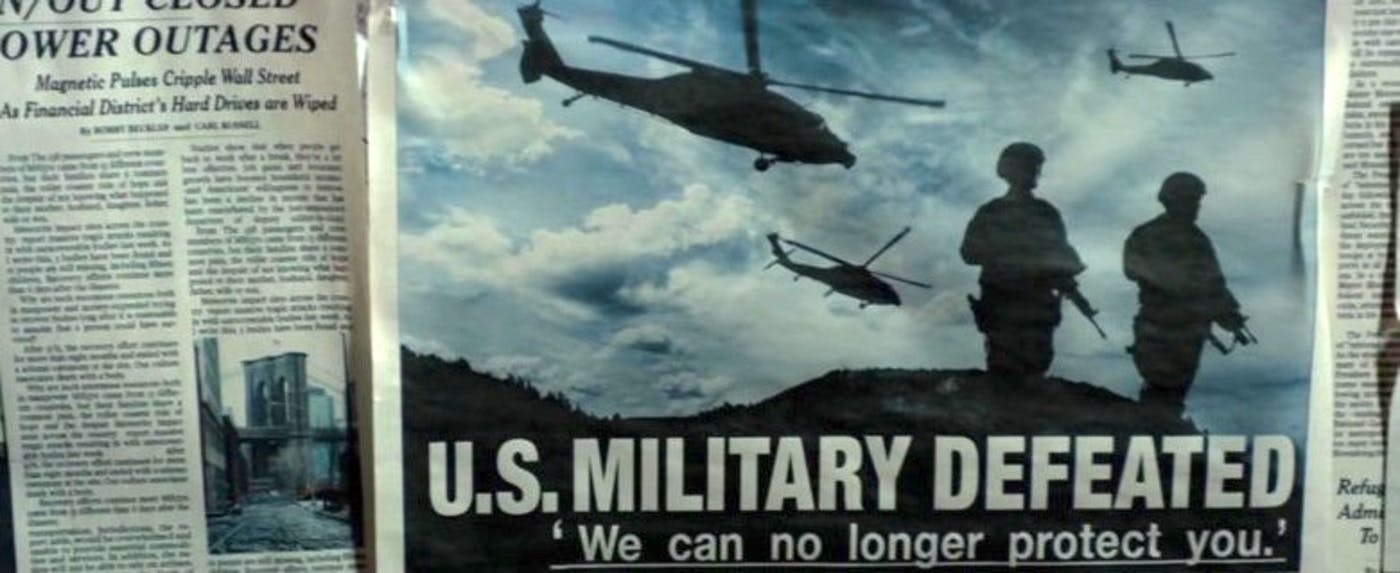

On the one hand, you can give A Quiet Place a boring, flat, but ultimately harmless reading: it’s about parents who have to sacrifice for children (basically just the definition of parenting). But, on the other hand, as a post-apocalypse movie, it invites you to believe that it’s saying something about society. And for the record, I don’t think it does. I don’t think John Krasinski has worked out the calculus of how this movie’s allegory works into the broader scope of sociopolitical-whatever at all. But. If you give this post-apocalypse movie the standard post-apocalypse movie reading (what causes society to break down, and what happens when it does?), this is a rural conservative / evangelical / doomsday-prepper / homeschooling / quiverfull-parent fantasy--one in which individual frontiersmen must uphold order after America's military has been rendered tragically powerless.

As Jared Gores from Reel Fanatics points out, this “fits so snugly into the religious right's family model” that “There's even a family dinner prayer scene!” Although the movie ends with a nod toward women taking charge (in which power is symbolized by gun ownership), this is only out of necessity--clearly, the more balanced patriarchal model of family life was more stable before a man’s absence gave way to all-out chaos. The idea that this is a movie about the virtues of raising your children in a bubble isolated from the rest of the outside world, teaching them to live off the land and work with their hands and trust no one, actually kind of explains the common question that many people have about A Quiet Place: why would anyone have a baby in this universe!? The answer: “be ye fruitful, and multiply.”

There’s also the probably unintended reading that explains why this movie is about sound in the first place. According to critic Adam Nayman, the movie is “just waiting to be stripped and sold as persecutory metaphor by free speech absolutists.” You know all the people you’ve heard complain about how “you can’t saying anything anymore without someone getting offended”? I think I know how they might interpret that opening sequence that shows the first person to make a noise be violently attacked by a previously offscreen monster: that’s an “SJW” attacking you for exercising your right to free speech! The monster design supports this too--not only are these monsters always listening for you to slip up, but they are basically all ear, which could potentially be a fantastical representation of how “people are just too sensitive nowadays.”

Again--I don’t actually believe that this is the way Krasinski intended the film to be read (unless he’s a closet Trump supporter or something--he was in that Benghazi film by Michael Bay, who produced this, you know...probably best not to think about it), but it’s not a stretch to say that the film’s central allegory could easily be interpreted this way by someone who harbors a resentment of globalism or PC-culture--and it would explain a lot more aspects of the movie than Krasinski’s boring, one-line interpretation does. The New Yorker’s Richard Brody, for example, sees this as the film’s truly obvious message, writing that “In their enforced silence, these characters are a metaphorical silent—white—majority, one that doesn’t dare to speak freely for fear of being heard by the super-sensitive ears of the dark others.” Yikes. Either the film is tonedeaf to its own implications, or it’s kind of sinister on a covert level. Whatever the case, I don’t think Krasinski is very wise to be citing Get Out as inspiration...

Krasinski says anything that "starts a conversation" between people is a net positive, even if their takeaways are totally at odds with one another. But that's not how allegory works; allegories about social systems can never be politically neutral. If Get Out, for example, validated anyone's blind trust in white liberal power structures, it wouldn't be a good allegory. My favorite film from the so-called "elevated horror" wave is The Witch, and it's pretty hard to read that movie as being about anything other than the historical disenfranchisement of women--it's commitment to that viewpoint is what makes the film's final scene so powerful, disturbing, and uplifting all at the same time. A Quiet Place does have its sights set pretty firmly on this parenting theme, but Krasinski cannot claim neutrality when he's also stumbling backwards into some fringe-right territory--and it's not as if focusing on the family is politically neutral in the first place.

CONCLUSION

Maybe I’m not giving Krasinski enough credit when I assume that his decisions are being made entirely by feel. It’s hard to tell how much of his phrasing and writing is intentionally wrongheaded and how much of it is just clueless. However, for the sake of argument I’m willing to take Krasinski at his word: he’s still figuring out horror, he wanted to make a movie about family, and, most importantly, he wanted to pay homage to his favorite “elevated horror” movies that have come out in recent years. On a basic level, he’s done that. The movie shares a lot of elements with its contemporaries: a streamlined structure, a slightly unconventional approach to scare tactics, a focus on character development over shock, and an obviously present allegorical subtext. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to do any of these things particularly well, however clearly they may have been laid out on paper. A Quiet Place feels a bit like an exercise in imitation or a skeletal outline of a horror movie--the product of Krasinski watching a few great movies all in a similar vein and saying to himself, “I could do that!”

And considering the broad success of movies like Get Out, It Follows, and The Babadook (which, despite limited theatrical distribution, found an enthusiastic audience in the world of streaming), A Quiet Place’s particular brand of horror is currently in vogue. As a result, many critics have been quick to unequivocally praise A Quiet Place as another example of unconventional horror firing on all cylinders. But a lot of what I’ve been reading about this thing is just parroting the marketing: It’s quiet! It’s terrifying! It’s about parenthood! It stars an actual husband and wife! Very few of these reviews, it seems, are engaging with the work itself--what it aims to do, how it works, and how it stacks up against its competition. From my perspective, A Quiet Place doesn’t quite measure up--not as a piece of visual storytelling, not as a delivery system for unconventional scares, not as a character-centric family drama, and certainly not as a well-told allegory. Thankfully, there are enough great horror films in the world to make up for the duds--and I genuinely think it would be interesting to see Krasinski return to the genre once he’s seen more of them.