Review by Lydia Creech

When it was announced the Coens had partnered with Netflix to produce a Western inflected “six-part anthology series,” I was cautiously optimistic. I’ve not been impressed with Netflix’s original content in the past, but I love the Coens…and I love Westerns. Thankfully, the Coens also have the same problem I do with television (“open-ended stories have a beginning and a middle — and then they’re beaten to death until they’re exhausted and die. They don’t actually have an end.”), which essentially means Buster Scruggs takes the form of six independent short films. I can see why the Coens teamed up with Netflix to release a film with this unusual format.

In their coverage of the Knoxville Horror Film Fest, Andrew and Jordan discussed the difficulty of accessing the quality of anthology films: does the overall effect add up to anything? Does the visual quality suffer? How do you frame it? What does it mean to only enjoy some of the segments? Do they only belong on Netflix (Coens say: “yeeessss?”)?

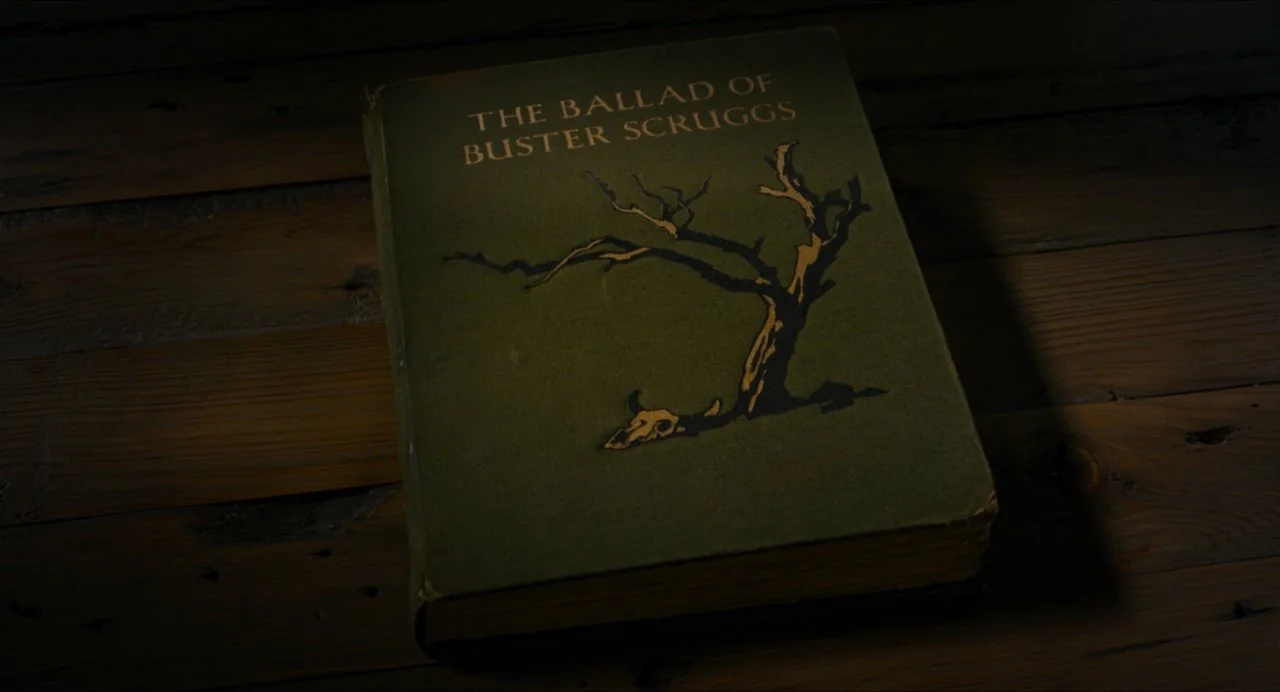

The Coens skirt the issue of a frame by literally presenting the audience with opening a book (a very Golden-Age-Disney move--but we’re dealing with a genre that basically amounts to American fairy tales…). All the stories are preceded by a “color plate” with an illustration of some moment from the story and then we go into it to find out what the context is. Because these are all little self-contained narratives, the Coens get a chance to explore different facets of what it means for a story to be a “Western.”

Each segment shows the Coens trying their hand(s) at a different subgenre, if you will. All of the segments rely on different tropes--we have a singing cowboy in “Ballad of Buster Scruggs,” hopeful homesteaders and Indian attacks in “Gal Who Got Rattled” (Zoe Kazan’s Alice is no Mattie Ross), and a Jack London Edenic valley in “All Gold Canyon” (legitimately a Jack London adaptation)--which works well within a short story framework to immediately let the audience get their bearings and catch up to speed on stakes. The Coens experiment with different visual styles and bring their flair for dialogue and penchant for nihilism to each (some literal gallows humor: “First time?” one condemned man asks another).

They’re not exactly mythbusting, but there is a bit of irreverence and poignancy to each story’s resolution. Sometimes fate will play the characters (“Near Algodones”) or they make cruel practical (to them) choices (“Meal Ticket”). Death touches each in small and large ways (and as an extended metaphor in the last segment, “The Mortal Remains,”). The Coens are obviously fascinated with the genre, and they’ve gotten the chance to do feature-length treatments several times in the past. Here in the short format, they get a chance to really flex their storytelling skills to quickly get the audience invested and then wrongfoot them. Even with the scope so scaled back, there’s great fun to be had in the execution, and I’d be more than happy with more of this from the Coens x Netflix.