By Mike Thorn

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Mike Thorn is the author of Darkest Hours, a collection of horror stories. His fiction has appeared recently in The NoSleep Podcast and Dark Moon Digest, and his film criticism has been published in MUBI Notebook, The Film Stage and Vague Visages. He completed his M.A. in English literature at the University of Calgary, where he wrote a thesis on epistemophobia in John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness (1987).

INTRODUCTION

About midway through the summer, I was inspired by Nadine Smith’s “Shmight and Shmound” poll, conducted through Twitter and also published here on Cinematary. I briefly toyed with the idea of leading my own poll for horror films and ran the idea past Nadine. She was extremely supportive and offered some helpful advice that came in handy during the (shockingly intensive) aggregating process. When I put out the call on Twitter, I quickly heard back from a wide array of fans, writers, bloggers, podcasters, critics and creators.

There were two things I was not anticipating when I first tweeted the call for ballots: first, the high level of engagement (I received nearly five hundred individual ballots altogether), and second, that several Twitter users would ask me how I was defining the genre. I intentionally left the term “horror” open to interpretation, but the boundaries and conditions of genre definition have fascinated me for some time. Some users submitted titles that would under most circumstances never be described as “horror” (everything from Dunkirk [2017] to Apocalypse Now [1979] to Ernest Goes to School [1994]), while others publicly questioned the validity of titles that I would argue clearly meet all possible criteria (for example, Jaws [1975], Eraserhead [1977] and The Witch [2015]).

Is it necessary to define the horror genre, or is it something that has been built into our general consciousness? I turn often to Stephen King’s statement in his 1985 study of horror cinema and fiction Danse Macabre, that “horror simply is, exclusive of definition or rationalization.” In some ways, King’s open sentiment anticipates John Clute’s argument in The Darkening Garden: A Short Lexicon of Horror (2006), that “since the beginning of the 1980s, it has become common to state not only that certain emotional responses are normally generated in the readers of horror texts, but also to claim that these responses are, in themselves, what actually define horror.” To that end, one might argue that Ernest Goes to School could be labelled horror every bit as readily as Cannibal Holocaust, given that a viewer experiences the affect denoted by the genre’s name.

While King and Clute’s statements speak to an artesian commonality imbedded within all horror films, I have come to grow increasingly suspicious of definitions that overstate the importance of its self-announcing affect. Horror is a distinct genre not only because of the subjective responses it incurs, but also because it stems from a history of recurring structures, motifs, images and philosophical premises. This final category of philosophical inquiry or confrontation might sound counter-intuitive, given the genre’s immediate and visceral nature. However, engagement with critical thought is, to me, fundamental to what the horror genre is and does. Consider Noël Carroll’s argument in The Philosophy of Horror that the kinds of monstrosities found within the genre “are not only physically threatening,” but “cognitively threatening […] challenges to the foundations of a culture’s way of thinking.” To me, this is one of horror’s most crucial tenets.

From a personal perspective, this does not mean that I more highly value horror films that strive for didactic or overtly “cerebral” approaches; contrarily, I would argue that too many titles in our recent wave of “prestige” or so-called “post-horror” genre films crumble under extraordinarily simplistic ideas played for faux-profundity (I’m not naming names, but a lot of the suspects got a lot of love in this poll). I submit that the genre has at its very foundation always been built on philosophical disruption: at its most effective, horror destabilizes our customary ways of interpreting that which we take for granted in material and social reality. As such, the last thing the genre needs is to be “elevated.” Horror should be combative, disturbing, rude and antagonistic to popular belief. It should be impolite. It should be feared. Naturally, the genre should and will adjust and respond to contemporary concerns and anxieties, often in ways that are unconscious, coded, located below that which is immediately apparent.

This list is relatively predictable in many ways, leaning heavily on popular late twentieth and early twenty-first century films (mostly American), but there are several surprises throughout: some of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s work seems to be getting a well-deserved surge in recognition, and some critically dismissed recent favorites like Rob Zombie’s Halloween II (2009) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Twixt (2011) received far more votes than I expected. Ultimately, I hope the list provides a helpful entry point for curious newcomers, or maybe even leads some lifelong fans to reconsider previously ignored films or discover something new.

FILM TWITTER’S FAVORITE HORROR FILMS: 2018

=145. The Black Cat (Edgar G. Ulmer, 1934)

=145. Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2010)

=145. Creepshow (George A. Romero, 1982)

=145. Day of the Dead (George A. Romero, 1985)

=145. Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives (Tom McLoughlin, 1986)

=145. Fright Night (Tom Holland, 1985)

=145. Goodnight Mommy (Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz, 2014)

=145. The Grudge (Takashi Shimizu, 2004)

=145. Halloween III: Season of the Witch (Tommy Lee Wallace, 1982)

=145. Hour of the Wolf (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

=145. Inside (Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury, 2007)

=145. Kuroneko (Kaneto Shindô, 1968)

=145. Love Massacre (Patrick Tam, 1981)

=145. Pet Sematary (Mary Lambert, 1989)

=145. Ravenous (Antonia Bird, 1999)

=145. Saw (James Wan, 2004)

=145. Twixt (Francis Ford Coppola, 2011)

=145. Zombie (Lucio Fulci, 1979)

=132. The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971)

=132. Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931)

=132. Gremlins 2 (Joe Dante, 1990)

=132. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (John McNaughton, 1986)

=132. It (Andy Muschietti, 2017)

=132. Kwaidan (Masaki Kobayashi, 1964)

=132. The Lords of Salem (Rob Zombie, 2012)

=132. A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (Jack Sholder, 1985)

=132. A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (Chuck Russell, 1987)

=132. The Orphanage (J.A. Bayona, 2007)

=132. Pontypool (Bruce McDonald, 2008)

=132. They Live (John Carpenter, 1988)

=132. Unfriended (Leo Gabriadze, 2014)

=116. Aliens (James Cameron, 1986)

=116. Cemetery Man (Michele Soavi, 1994)

=116. The Changeling (Peter Medak, 1980)

=116. Christine (John Carpenter, 1983)

=116. Demons (Lamberto Bava, 1985)

=116. The Devil’s Backbone (Guillermo del Toro, 2001)

=116. The Exorcist III (William Peter Blatty, 1990)

=116. Inferno (Dario Argento, 1980)

=116. Insidious (James Wan, 2010)

=116. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956)

=116. Lost Highway (David Lynch, 1997)

=116. Phantasm (Don Coscarelli, 1979)

=116. Raw (Julia Ducournau, 2016)

=116. Se7en (David Fincher, 1995)

=116. The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984)

=116. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (Tobe Hooper, 1986)

=108. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995)

=108. Funny Games (Michael Haneke, 1997)

=108. Häxan (Benjamin Christensen, 1922)

=108. Martin (George A. Romero, 1978)

=108. Messiah of Evil (Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, 1973)

=108. Near Dark (Kathryn Bigelow, 1987)

=108. The Seventh Victim (Mark Robson, 1943)

=108. Tenebrae (Dario Argento, 1982)

=97. Cannibal Holocaust (Ruggero Deodato, 1980)

=97. The Devil's Rejects (Rob Zombie, 2005)

=97. Ginger Snaps (John Fawcett, 2000)

=97. Gremlins (Joe Dante, 1984)

=97. Horror of Dracula (Terence Fisher, 1958)

=97. The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933)

=97. Manhunter (Michael Mann, 1986)

=97. New Nightmare (Wes Craven, 1994)

=97. Phenomena (Dario Argento, 1985)

=97. The Sixth Sense (M. Night Shyamalan, 1999)

=97. Split (M. Night Shyamalan, 2016)

=89. Curse of the Demon (Jacques Tourneur, 1957)

=89. Event Horizon (Paul W.S. Anderson, 1997)

=89. Freaks (Tod Browning, 1932)

=89. Green Room (Jeremy Saulnier, 2015)

=89. Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001)

=89. Opera (Dario Argento, 1987)

=89. [Rec] (Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza, 2007)

=89. Shaun of the Dead (Edgar Wright, 2004)

=81. Braindead (Peter Jackson, 1992)

=81. Dead Ringers (David Cronenberg, 1988)

=81. Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931)

=81. The House of the Devil (Ti West, 2009)

=81. Jacob's Ladder (Adrian Lyne, 1990)

=81. Kill List (Ben Wheatley, 2011)

=81. Trouble Every Day (Claire Denis, 2001)

=81. Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013)

=76. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920)

=76. Dracula (Francis Ford Coppola, 1992)

=76. The Fog (John Carpenter, 1980)

=76. Nosferatu (Werner Herzog, 1979)

=76. The Others (Alejandro Amenábar, 2001)

=70. The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955)

=70. Onibaba (Kaneto Shindô, 1964)

=70. Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960)

=70. Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1998)

=70. The Vanishing (George Sluizer, 1988)

=70. The Whip and the Body (Mario Bava, 1963)

=68. Halloween II (Rob Zombie, 2009)

=68 The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976)

=63. The Beyond (Lucio Fulci, 1981)

=63. The Brood (David Cronenberg, 1979)

=63. The Conjuring (James Wan, 2013)

=63. Perfect Blue (Satoshi Kon, 1997)

=63. The Ring (Gore Verbinski, 2002)

62. Martyrs (Pascal Laugier, 2008)

61. Black Christmas (Bob Clark, 1974)

=59. In the Mouth of Madness (John Carpenter, 1994)

=59. The Return of the Living Dead (Dan O’Bannon, 1985)

=57. Deep Red (Dario Argento, 1975)

=57. Inland Empire (David Lynch, 2006)

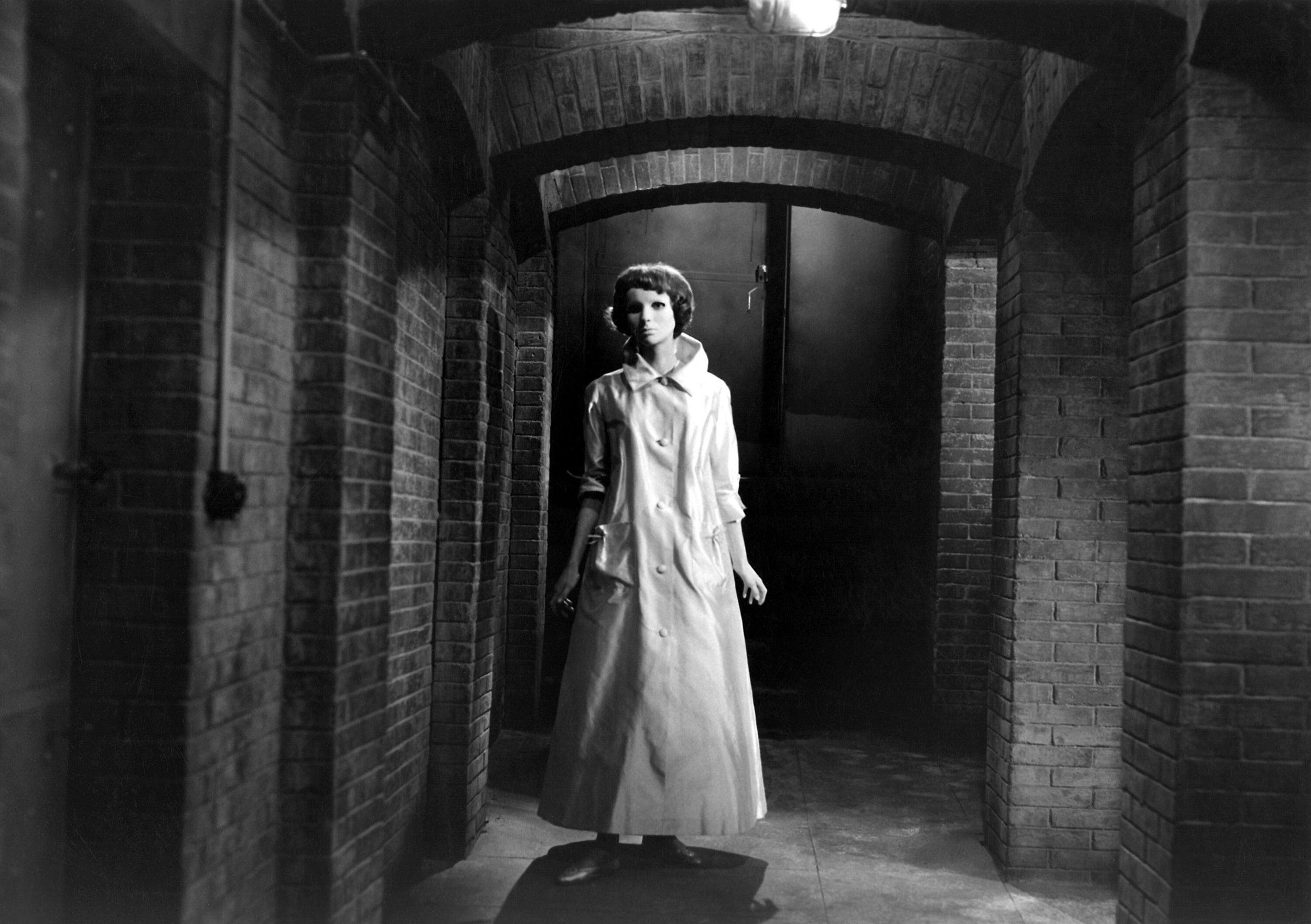

56. Repulsion (Roman Polanski, 1965)

55. Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962)

54. 28 Days Later (Danny Boyle, 2002)

53. Hausu (Nobuhiko Ôbayashi, 1977)

=51. The Cabin in the Woods (Drew Goddard, 2012)

=51. The Innocents (Jack Clayton, 1961)