By Zach Dennis, Andrew Swafford, Jessica Carr, Lydia Creech and John McAmis

**NOTE** This is not in ranked order

Yourself and Yours (2016) by Hong Sang-soo

I’ve heard it said that Hong Sang-soo is a bit of a one trick pony, but it’s a fabulous trick. Yourself and Yours tells the story of a guy and girl, and they begin the film with an argument about her drinking (though I wouldn’t say this film is as drunken as some of his others).

They break up, and the guy spends the rest of the film trying to win her back… but she doesn’t remember him? Or… she’s pretending? To teach him a lesson?

Regardless, the effect is the same, and we get another exploration from Sang-soo of relationships where the devil really is in the details (his thematic concerns are always the same, as far as I can tell, but there’s tons to explore within those so it doesn’t get old).

It’s actually much cuter than I’m getting across here, and, of course, it’s delightful to witness Hong Sang-soo work his magic. In the broadest possible terms, comedies (any narrative?) are structured as Stability-Chaos-Return. Here, Hong Sang-soo literally brings us full circle (and that’s not really a spoiler). I’ve only just discovered his films this year, but he’s apparently super prolific (See: TWO films making this list), and everything I’ve seen so far has been as playful and engaging as the last. - Lydia Creech

Little Men (2016) by Ira Sachs

Life can seem so enormous from its smallest sectors.

This rings true for most of writer/director Ira Sachs films, but is even more pronounced when looking at the story being presented in Little Men. There isn’t much space between where Jake (Theo Taplitz) lives and where Tony (Michael Barbieri) does and that helps to blossom a friendship between the two.

They both come from different worlds also. Jake is moving into the building after his grandfather passed away and left his Brooklyn apartment to Jake’s father, Brian (Greg Kinnear), a theater actor. Brian and his wife, Kathy, move into the apartment and begin a dialogue with Tony’s mother, Leonor (Paulina Garcia), who owns the shop at the bottom and struck a deal with Brian’s father to have an affordable rate in order to keep her business open.

The two boys bond quickly over video games, art and girls, but it doesn’t seem like they get to control their friendship as all the while Brian and Leonor struggle to come to an agreement over keeping her business in the building that culminates in an outburst and severed ties.

The tragedy is less that these two families are unable to find a middle ground, but that these two boys are unable to grow more together because of the spat. All of this comes together when Jake notices Tony on the other side of a museum a few months after the events of the story. Jake is now going to the art school the two boys always dreamed about attending while Tony is going to a less prestigious institution.

Was Jake in love with Tony? Was there a homosexual element to their relationship? Maybe, but that isn’t important. When Jake notices Tony across the museum, he yearns for those fun moments of their “summer fling.” And after the credits roll, Sachs leaves us yearning for more stories as personal and satisfying as this. – Zach Dennis

No Home Movie (2016) by Chantal Akerman

Chantal Akerman’s final and most personal film is documentary about her mother, shot in Akerman’s signature slow cinema style. Though not as lengthy as her masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, No Home Movie borrows many stylistic and thematic elements with which viewers of Akerman’s work will be familiar. Long, static, poignant shots of doors and frames. A quietness throughout that permeates the viewer’s senses. A focus on the lives of women and their day-to-day routines. Akerman’s film documents the last days of her mother before her death.

The two women, mother and daughter, are seen conversing about almost anything - their family, the weather, their past week. It’s a universal film about the relationship between a mother and her daughter, what a bond that is and how powerful it can be. Akerman herself passed away shortly after the premiere of the film in 2015, leaving an incredible filmography behind. - John McAmis

Miracles From Heaven (2016) by Patricia Riggen

This one was hidden in a landfill of disposable faith-based movies like God’s Not Dead, Facing the Giants, Heaven is for Real, and I Am Not Ashamed, many of which frame Christendom as a monolithic army of truth-tellers, locked in mortal battle with a godless secular society. With that context in mind, I really don’t blame anyone for not giving Miracles from Heaven a second glance. However, I hereby urge you to reconsider that dismissal, as Patricia Riggen’s film gets something unequivocally right about faith: it’s personal.

This is not the story of an evangelical family proving to the rest of the world that miracles are more reliable than science; it is the story of a mother trying to reconcile her belief in a loving god with her daughter’s senseless suffering due to incurable disease.

The mother in Miracles is played by Jennifer Garner, who brings a raw emotional honesty to the performance, always revealing for the audience a complicated humanity shaped by experience rather than dogma. When her pastor--who, understandably, wishes to find order in God’s universe--implies that her daughter’s suffering must have a root cause in unrepentant sin, we instinctively mimic Garner’s the-audacity-of-this-motherfucker look of astonished indignation. When a decidedly not monstrous father of another terminally-ill-kid politely tells Garner that he feels uncomfortable with the false hope of a miracle-from-God being planted in his kid’s head, we instinctively mimic Garner’s of-course-you’re-right look of sincere apology. And, tellingly, when Garner delivers the line, “I don’t have faith in anything. I can’t even pray,” the movie does not orchestrate ominous music and loud thunderclaps to make us hate her.

Of course, the movie does circle back around to the importance of faith and the reality of it’s namesake (though even this leaves room for doubt--notice how the surreal heaven sequence pulls visual cues from art featured elsewhere in the film, implying that it could be just a dream), but only after allowing the protagonist to genuinely question and deny Christianity with no judgement. This is a profound step for faith-based cinema--the understanding that religious belief is a personal journey rather than a call to arms. - Andrew Swafford

Barry (2016) by Vikram Gandhi

“You know, every time I open my mouth in class, it's like... I'm supposed to speak on behalf of all Black people. Meanwhile, I, uh... I quit going to Black Student Union meetings because I didn't feel like I belong there either.”

Before Barack Obama, there was Barry (Devon Terrell). He was a college student at Columbia University struggling to find his racial identity amidst the tensions that were presented in 1981’s America. He went to parties, drank beer, and said a few curse words. He went on dates with Charlotte (Anya Taylor-Joy) and even she could not understand what goes on in his head. This guy is a thinker. He doesn’t understand the world, but he wants to.

The portrait that director Vikram Gandhi paints of our former president is a compelling one. In Barry, a college student goes through the same questions that most of us go through. He searches to find what his purpose is and at the end of the film he still isn’t sure. Terrell shines as Barry. He adds humanity and depth to his character.

The film isn’t the best biopic and I haven’t seen Southside With You, so I don’t even know if it’s the best Barack Obama film. But, I do know that Barry is a beautiful snapshot of a man’s life who would go on to inspire so many others in the 8 years that he serves as our 44th president. And it is a film that I think the American people need now more than ever before. - Jessica Carr

Right Now, Wrong Then (2016) by Hong Sang-soo

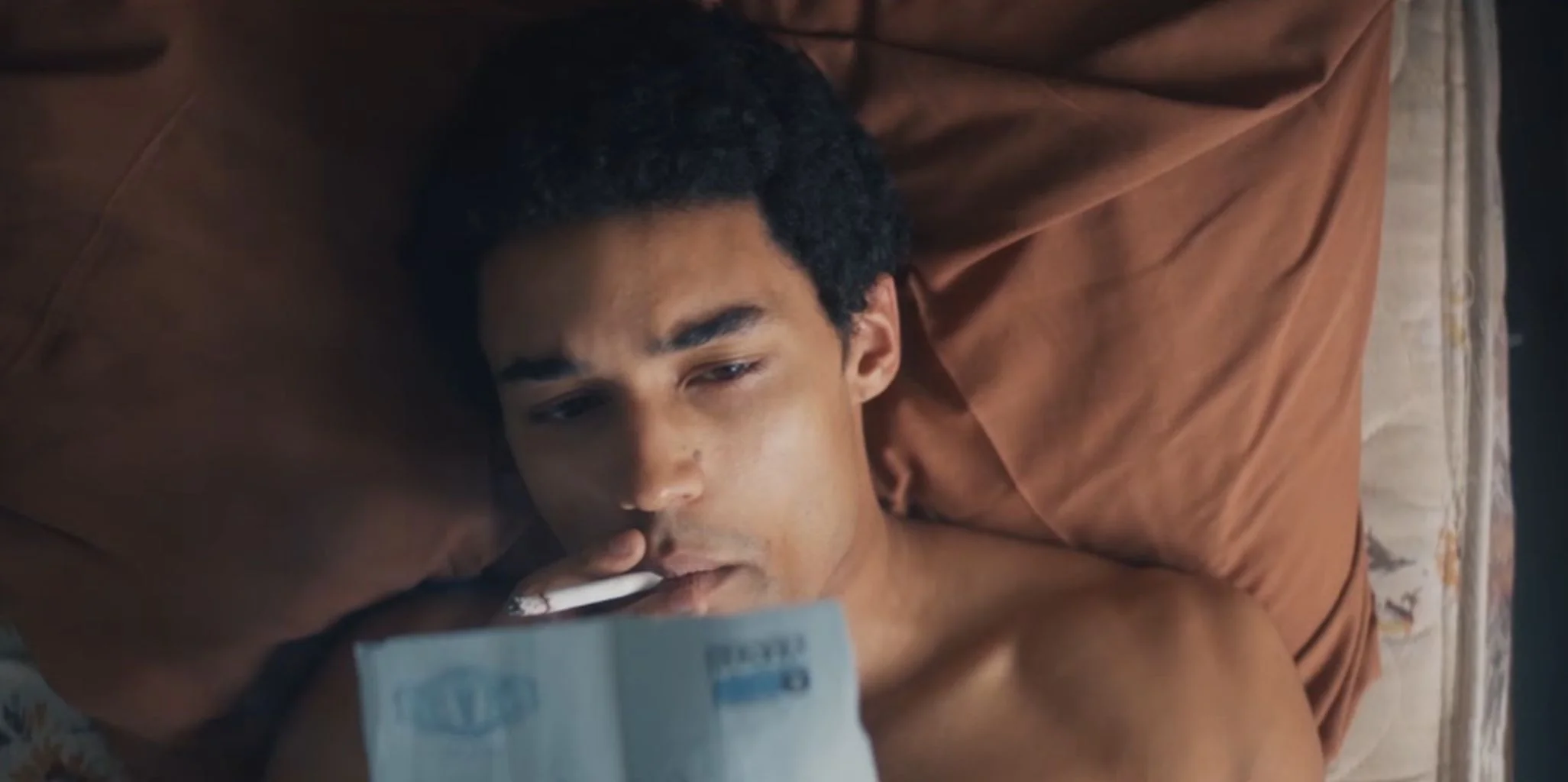

The picture above is not taken directly from Right Now, Wrong Then, but it captures the essence of Hong Sang-soo’s visionary romantic comedy. The film is a simple story of two strangers who meet in public and decide to spend a mundane day together, but it ends up accumulating into something nearly cosmic in scope without ever leaving the ground.

The cinematography of this film is not showy, but almost every scene is formed by a static camera capturing two people in extended conversation, unbroken by cuts between different camera angles. The audience’s perspective is ever-so-casually forced, allowing ample time for the viewer to become intimately familiar with every minute aspect of the set and the performers’ mannerisms. Therefore, when settings are returned to--but from a slightly different angle--or when scenes are inexplicably repeated--but with a slightly different outcome--one can’t help but notice all the tiny differences that alter the course of the entire narrative. Notice new hand gestures, notice posture changes, notice differences in tone of voice. After a first date, these are the things that keep us up at night. Could these insignificant details determine our course to true love or deep resentment? Right Now, Wrong Then posits that they do.

This is a co-production between two different ends of the multiverse, and I love Hong Sang-soo for his multidimensional approach to personal storytelling, which is fraught with self-deprecation and ego-interrogation. Jung Jae-young plays the director’s authorial stand-in (think Owen Wilson as Woody Allen in Midnight in Paris, or Jesse Eisenberg as Woody Allen in Café Society--they’re all Woody Allen), and he does so like a true doofus, completely unaware of his own absurdity even as he slowly strips naked at a dinner party in a drunken stupor. Playing his opposite is the unbelievable Kim Min-hee, who shows mind-boggling range between her understated performance in this and her explosive amorousness in Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden (about which our site features a long-form essay and a place on the "Best Foreign Films of 2016" list).

I can’t recommend Right Now, Wrong Then highly enough--and if you like it, there’s so much more delight to be found in Hong’s prolific film catalogue. - Andrew Swafford

Cameraperson (2016) by Kirsten Johnson

Kirsten Johnson has worked as a documentary cinematographer for many years, traveling the world and amassing thousands of hours of footage in the process. Most of her footage, as any filmmaker knows, was not used and therefore left on hard drives and SD cards for years. Johnson, after shooting all this footage, aggregated her surplus clips into a 103-minute cinematic memoir.

Such a thing could be lame, banal, and slow, but Johnson’s eye as a cinematographer and rhythmic pacing of the film allows the viewer to enjoy and become engrossed in the images. She introduces the viewer to a random location for a few frames, allows us to acclimate to that region of the world, reveals its location with an inter title, then lets the scene play-out before moving onto another location. Nigeria, Bosnia, Romania, and other countries are featured, showcasing not only the places to which Johnson has traveled, but also the people with which Johnson has interacted.

Cameraperson, ultimately is a memoir of Johnson’s career as a cinematographer, but it also is one of the more beautiful ways to see the world and cultures that are not so different from our own. - John McAmis