Review by Andrew Swafford

I have a copy of Paradise Lost with a foreword from Philip Pullman, and in it he provides one of my favorite quotes about cinema and storytelling: “Alfred Hitchcock once pointed out that if a film opens with a shot of a burglar breaking into a house and ransacking the place, and then, with him, we see through the bedroom window the lights of a car drawing up outside, we think ‘Hurry up! Get Out! They’re coming!’” Perhaps no movie attempts to illustrate Hitchcock’s point more than Don’t Breathe--a home invasion film from the perspective of the invaders, who rob a blind veteran in order to get enough cash to escape an impoverished life in a post-auto-crisis Detroit. Because director Fede Alvarez and his writing partner (Rodo Sayagues Mendez) flip the script on such a standard horror narrative, Don’t Breathe sets itself up as an extremely compelling genre exercise, with stakes that matter, a world you understand, and characters you identify with on both sides of the conflict. The film doesn’t necessarily maintain that grounded level of tension for the entire runtime, but...it’s great while it lasts.

The whole conceit of having characters sneak through a blind man’s house makes for great horror cinema, mostly because of the way it allows the movie to play with volume. The American horror film industry is all about volume--but one look at practically any mainstream horror trailer reveals that Spinal Tap’s Nigel Tufnel must be the one cranking the knobs. On the other hand, Japanese horror films like Pulse often revel in uncomfortable silences paired with unsettling visuals (a friend of mine calls this “Deal-With-It-Horror”) without stabbing their audiences in the ears to punctuate each shot. For almost half the runtime, Don’t Breathe restrains itself to the expectations of the latter, as the film’s characters are motivated (as the title suggests) to be absolutely silent while essentially playing a life-or-death game of hide and seek--which makes scares possible with only small disturbances, like a cell phone vibrating unexpectedly. This makes for great filmmaking not only because it’s nice to not have my eyes/ears sadisticly violated by non-diegetic screams, but also because it’s more effective than the standard technique would be. This is a tense and frightening film, not in spite of pulling back the reigns on jumpscares and volume blasts, but because of it.

The lack of over-the-top scares in the first half of Don’t Breathe goes along with the world created by the film, too--it has a great sense of realism and physicality to it. Almost the entire story takes place in one house, and (as What The Flick pointed out in their review) the geography of that house makes sense. Thanks to good editing/blocking and a nice long tracking shot early on, you know where all the characters are in relation to each other and how sound travels throughout the house--and finding a new room the characters didn’t know existed before is a downright revelation. This is important and so helpful to the craft of Don’t Breathe because of how well it tells its story almost solely through physicality. There’s not a lot of chattiness in Don’t Breathe, and motivations/conflicts are never explained to the audience in a condescending way; it’s all visual, having to do with how bodies interact and maneuver through space. Again, the conceit of the characters having to behave stealthily makes for some damn good cinema.

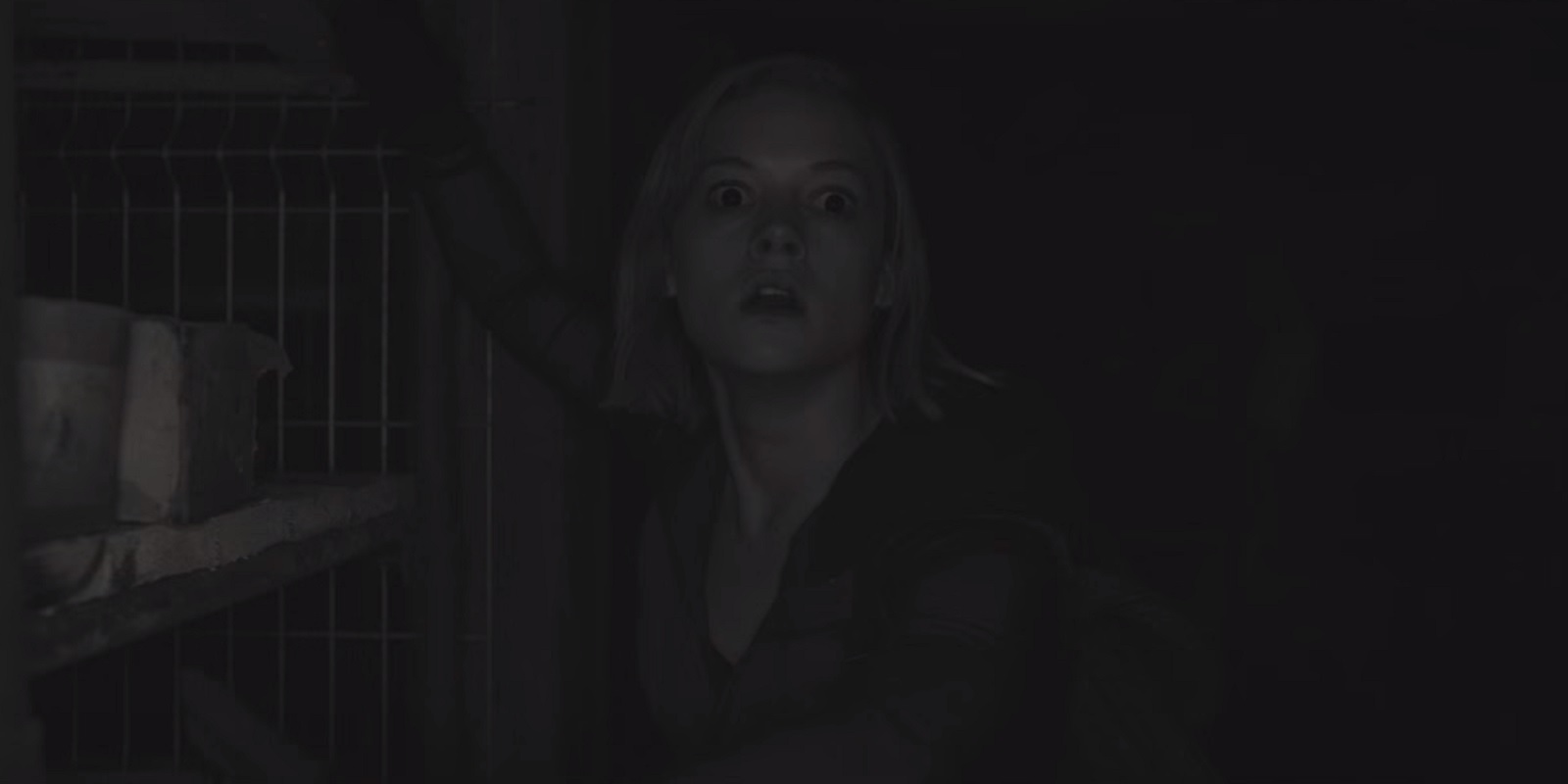

My favorite sequence of the film (worth the price of admission, really) takes the idea of understandable geography and adds visual flair to it, when the blind man attempts to trap the intruders in his basement by flipping the breaker, essentially giving them the same handicap he has. He has been living with this disability and knows the space better than they do, so he can continue giving chase unphased, while the film’s protagonists are incapacitated. Alvarez’s cinematographer (Pedro Luque) shoots darkness here in a way I’ve never quite seen before--rather than cutting to black, the shot goes from full color to an extremely smooth grayscale (see header image) that makes the dividing lines between characters and environments negligible. The closest comparisons I could make are to Villenueve’s Sicario, which uses military-style heat sensors to allow its characters/audience to see in the dark, as well as one scene in Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs, which shows Clarice Starling fumbling in the dark while a predator looks on at her with night-vision goggles. In Don’t Breathe, the presentation of darkness utilizes no high-tech wizardry--it just decreases the efficacy of the human eye in a way that feels true to concept.

And that’s where the thing falls apart--being “true to concept.” Without spoiling anything, I have to report that about an hour into Don’t Breathe, things start to go off the rails. Although the film succeeds so well in its first hour by having a compelling sense of realism and physicality, these things don’t last. The film gets progressively more shrieky, loud, and brutal in its final act, conforming to mainstream horror convention and betraying what made the thing interesting in the first place. As the violence becomes escalated, the characters eventually have to sustain more and more ridiculous injuries that would undoubtedly be life-ending (especially for a 70+ year old, right?!) if the film’s runtime didn’t require them to get back up minutes later to serve as deus ex machina for another character in peril. Additionally, seemingly resolved conflicts keep getting revived for just one more scare again and again and again. I got the sense that, plot-wise, the writers had painted themselves into a corner--the whole concept is to never leave the house, but once the owner and intruders all know about each other, where can you go from there aside from ramping up the violence?

(This is also supremely frustrating for spoiler-heavy reasons: when a new character is revealed out of nowhere, the film starts to finally open itself up to new possibilities. But then that character dies within minutes, and we’re back to the same old cat and mouse game.)

Most of the violence just seems a little Tom and Jerry after a while, honestly, with the protagonists and the antagonist exchanging countless gunshot wounds, stabbings, punches to the face, until one of them falls over only to get back up minutes later. And aside from the formal problem this presents for the film, it borders on abuse towards the audience as well. Last year I felt a similar conflictedness towards the Austrian horror film Goodnight Mommy, which had an incredible set-up but just became a black-hearted torture-fest at the end that I couldn’t tolerate. Don’t Breathe doesn’t go quite as far into cruelty territory as that film did, but the endless escalation of small-scale violence certainly becomes gratuitous after a point.

However...one scene in particular crossed a serious line for me, and I don’t mind spoiling it just to give a sense of how ridiculously over-the-top and mean this movie’s violence gets near the end. (Feel free to stop reading here if you don’t want the spoiler or just don’t want an awful image in your head, by the way.) Here’s the plot point: a woman regains consciousness to find she has been tied up to a mechanical contraption on the ceiling, and her captor explains to her that he’s going to keep her that way until she has his child. “I’m not a rapist,” he explains, as the contraption raises her into the air and spreads her legs. He then pulls out a turkey baster full of his own semen and cuts her pants open with a knife. While she screams and shakes with panic, the film then makes it appear that he has rammed the thing inside her, when in fact it is he who has been sledgehammered in the back by the heroic heartthrob we thought was dead in the last scene, but who now is here to save the damsel. So many problems with the film’s final act are present in this sequence: it’s cheap, it’s manipulative, it’s nonsensical, it lies to the audience, and as a totally unnecessary kicker, it exploits unspeakable cruelty towards women as a set-up for a nice-guy male savior. (The rest of the film is uninterested in this gender dynamic, for the record, and the female protagonist definitely holds her own later on in the film--but that’s doesn’t diminish how awful this one particular moment is as an audience member.)

I’m so torn on Don’t Breathe. How can a film be such a bold, cinematic breath of fresh air for over half its runtime and then be so dunderheaded and unforgivably, stupidly cruel in its final act? I chalk it up to a combination of two factors: (1) standard horror conventions giving Alvarez conscious or unconscious pressure to create a batshit crazy final act, and (2) Alvarez wanting to keep all his characters contained in a single location but eventually running out of worthwhile things for them to do in said location.

It was a huge disappointment for me, personally--but admittedly, most audience members will probably not share my complaints! The audience I saw this thing with loved it--they were likely the same demographic (and at the same theater!) who heckled The Witch earlier this year. And I’m fine with that--not everybody wants to see The Witch when they go to see a horror movie on a Friday night. That audience deserves a well-made horror movie too, and Don’t Breathe is a well-made horror movie. I just wish it made good on its promise to be good without being cheap.