Review by Nadine Smith

There is perhaps no genre more maligned and misunderstood than the action movie. The Western is respected and the musical revered. Gangster movies and film noir are the ooze that runs through the veins of American cinema. Horror movies are ripe and rupturing with subtext. But what’s the worth in action?

For lay viewers, the action genre might be enjoyable but is ultimately disposable; for more self-serious audiences, action movies are a ghetto that the more “respectable” likes of The Raid and Nicholas Winding Refn need to gentrify. Enjoyment of most of the best action movies of the decade so far (Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning; Dredd; Resident Evil: Retribution) will get you accused by some cinephiles of, at best, populism; at medium best, vulgar auteurism; at worst, contrarianism. Action movies are left for the Armond Whites of the world, people who, according to Dissolve comment threads and the Letterboxd-industrial complex, don’t actually like what they claim to like. There’s no sincerity in action movies, only surface, right?

But it’s in the surface of action movies where the sincerity and subtext lies. The beatification of Michael Bay and apotheosis of Paul W.S. Anderson might look like a joke to people who aren’t in certain Internet circles, but it’s not. This was something I don’t think I realized until last September, when I first viewed John Woo’s The Killer. In terms of narrative, Woo’s language is melodrama, one of the classic modes of movie storytelling. Guy Maddin defines melodrama as “hyperbolized real life or life lived uninhibitedly”; melodrama is uncompromised by convention, unconcerned with social norms or mores, and “over-the-top.” If Woo wants to enhance his emotional or narrative melodrama visually, the action of his movies must also be uncompromised by convention, unconcerned with social norms or mores, and “over-the-top.” And for those who have seen Woo’s signature pictures, it’s quite obvious that the two work together. To bring it back out to a broader context, the best action movies are not just surface; that surface exists in tandem with subtext or narrative. Images and emotion should always mirror one another, but with action movies, a symbiotic relationship is even more necessary.

SPL 2: A Time for Consequences, Cheang Pou-soi’s sequel in-name-only to Wilson Yip’s 2005 film SPL: Sha Po Lang, exemplifies this relationship. Within the space of SPL 2, everyone is connected, either by familial blood or the blood that they shed. The main narrative conflicts of the film arise between ruptures in these relationships: the inability of a father (Tony Jaa) to restore the health of his daughter, the inability of an uncle (Simon Yam) to rescue his nephew (Wu Jing) from a Thai prison, the inability of a dying crime lord to secure the literal heart of his brother. As the father tries to find the only possible bone marrow donor for his sick daughter (who happens to be the wrongful prisoner played by Wu Jing), the issue is communication: he speaks Thai, but the donor only knows Cantonese. A translation app helps them overcome the distance.

But within the space of SPL 2, technology is just as good at tearing apart as it is at bringing together. The donor is dealing with a communication issue of his own: if he wishes to escape from prison, he must secure a phone (and phone signal) to reach his uncle in Hong Kong. Toward the beginning of the film, a transportation terminal, a place in which we are scrubbed of time zones and national identities and brought together in a mutual sense of arrival and departure, is turned into a space of disruption through a shootout. Technology and transportation allow for greater geo-political interaction and should fuse us together, but in these instances, they break individuals apart. The only dependable conduit for conveyance is the human form.

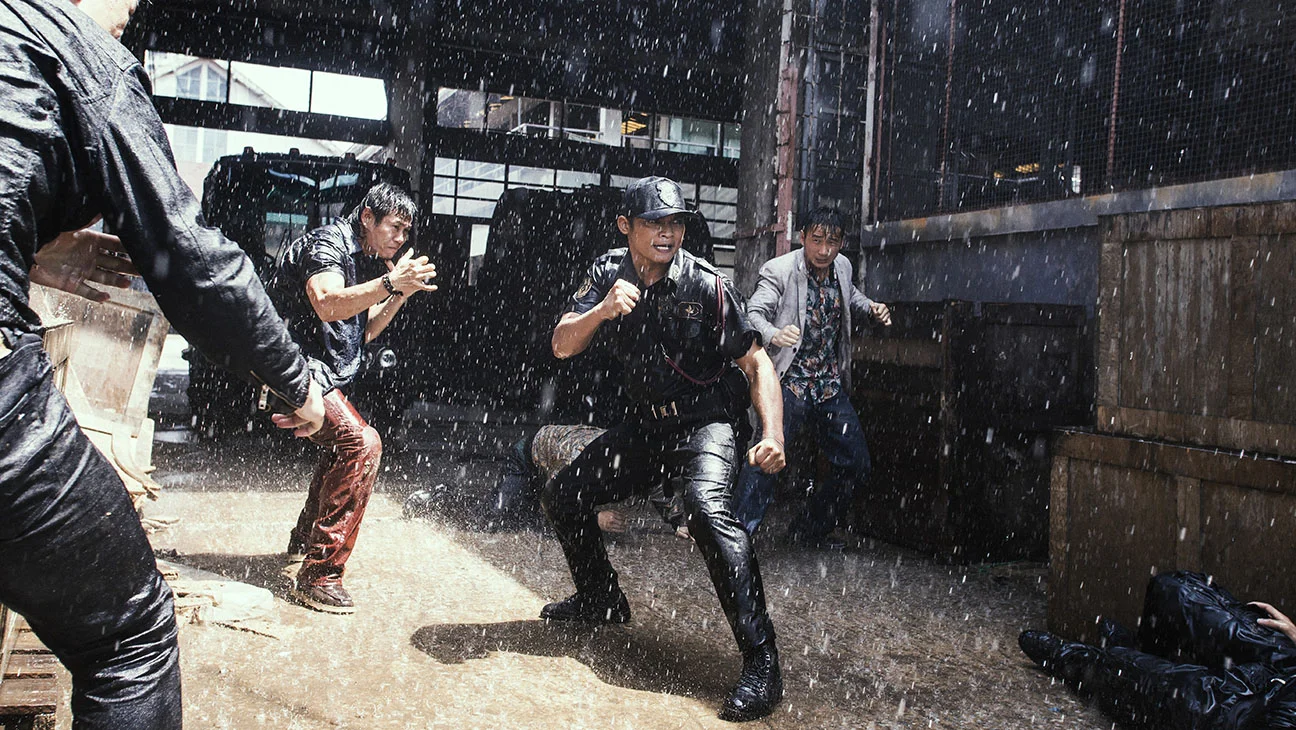

The distance in relationships that SPL 2 reckons with is manifest not just in narrative but in action. Tony Jaa is from Thailand, Wu Jing from China. Jaa’s martial arts background is in muy thai, Wu’s in wushu. At first their bodies are opposed to one another because of miscommunication, but by film’s end, they unite physically against a common enemy, the black market organ kingpin who would disintegrate their bodies. When language and technology break down, action and movement are all that’s left to join the two together. The film’s villains don’t want to kill our protagonists; they want to destroy their bodies, to remove any chance at connection and communication. There is a ferocious architecture to each series of blows, a careful construction to every slash, stab, and slice.

SPL 2 is like the Mountains May Depart of martial arts movies: a familial melodrama about communication across cultures recast as an action picture. SPL 2’s sense of violence is hereditary, not romantic, in its melodrama- born not of a wanting for connection to others, but of a being linked to others, that tactile experience of being all of us feel the moment we are born into or embraced by a family unit. These bodies signify bodies. They are not placeholders for thoughts or themes or ideas; they only symbolize their status as vessels of bone and blood related to other vessels of blood and bone. Like the best action movies, SPL 2: A Time for Consequences is a surficial melodrama in visual communion with its subtext. It isn’t about the disruptive power of violence, but about bodies jointed in impact and contact, united in their movement through space.