Review by Andrew Swafford

Laurie Anderson is a softhearted polymath. She started her career as an illustrator, but later shifted her focus to work as a poet and a performance artist. Most know her, however, as a composer and a musician—I, like many, adore Anderson’s 1982 album Big Science, which is a madly cerebral mixture of minimalist classical music, experimental electronic music, and spoken word poetry that offers a cryptic commentary on the newly-techno-age America with both clinical stillness and great portent. Crucially, Anderson is also somewhat of an inventor, and created an electronic violin that operates primarily with magnetic tape, which fundamentally shaped the sound of Big Science and many of her other studio recordings. Now, Anderson can add “filmmaker” to her list of many titles, and her debut feature has already earned a spot in the prestigious Criterion Collection. In my eyes, she deserves the honor. Heart of a Dog (which Anderson wrote, directed, produced and scored) isn’t just a film by a musician for fans of that musician—it’s a proper film in every sense of the word, with breathtaking editing and camerawork, great poignancy and insight, and a unique approach to storytelling that radiates the brilliance of Laurie Anderson’s sensibilities as an artist in any medium.

Just like Anderson herself or even just her musical output, it’s hard to pin down what exactly Heart of a Dog is like. On a surface level, it’s mainly a documentary tribute to the director’s recently deceased Rat Terrier named Lolabelle, who was a kind of amazing creature. For example: Anderson and a dog-trainer taught Lolabelle to both paint and play the piano (watching this in film form is nothing short of fantastic—I witnessed a theater full of very serious classical music aficionados lose their minds with giggling). But in looking into the microscope to examine the dog’s life, Anderson’s gaze refracts into dozens of other directions and creates a beautiful constellation of ideas about all kinds of heavy human-condition stuff that it feels absurd to actually write down or say out loud.

Perhaps the most easily crystalized example of this would be when Anderson narrates a memory of Lolabelle almost being attacked by a hawk, which had mistaken her from afar for a small rodent before turning around and flying away. Anderson imagines the shaken Lolabelle’s thought process after this experience, and she deduces that the dog must have learned three things: (1) her life could be threatened; (2) such threats could come from the air; and (3) this could happen at any time. Anderson likens this mental state to that of Americans (particularly New Yorkers, of which Anderson is one) after the September 11th terrorist attacks (which are kind of spooky to talk about in relation to Anderson, as her 1982 breakout song "O Superman" evokes so much imagery that seems to prophecy the event). This gets Anderson into a spiral about surveillance and big data that might be perceived as just drug-induced free-association if you didn’t trust her authorial voice, tender heart, and stone-cold intellect so much.

It’s important to stress that the 9/11 connection is just a small example of how Anderson uses her dog’s life to touch on other subjects—Anderson also uses moments from her dogs life to compare the anatomies of humans and animals, to discuss her practice of Buddhism, to reflect on her own childhood memories recovering from injuries in hospitals, and to examine her mother’s own recent death. Like Chantal Ackerman’s final film, No Home Movie (discussed on Episode 86 of Cinematary), Anderson’s Heart of a Dog works as an intimate meditation on grief, which is all the more poignant if one takes into account a major biographical detail that Anderson DOESN’T touch on in the film: the recent death of her husband, the revolutionary proto-punk/experimental musician Lou Reed (of The Velvet Underground fame). The main difference between No Home Movie and Heart of a Dog is that Anderson’s film seems to me to be profoundly more uplifting and entertaining. These films serve different purposes, of course, and I don’t mean to knock Ackerman’s tribute to her mother at all—but I just hope to communicate that Heart of a Dog isn’t the dour, morbid experience you might be imagining it is.

This might come across as overly academic or elitist (I don’t mean it to), but what I love about Heart of a Dog above all things is the way it demonstrates what it means to have true intelligence—something I don’t stake any serious claim to. I’ve heard (from PBS IdeaChannel’s video about Google data) about John Locke’s theory that knowledge is not just stored information and ideas, but the ability to make connections between and USE that stored information and ideas for a meaningful purpose. Laurie Anderson—in Heart of a Dog, specifically—is the personification of this idea. Throughout this entire film, she is constantly bringing together disparate personal experiences, works of art, scientific research, and major world events to make true intellectual sense of something as seemingly insignificant as the death of a pet. She has so much information being processed in her head, and none of it is trivia—every piece informs the way she sees and interacts with the world. (It makes perfect sense to me, now, that Anderson soon got bored of the standard violin—she needed magnetic tape violins and later MIDI violins to synthesize multiple musical ideas at once.) Watching that thought process happen on screen is inspiring to me as a human being who regularly just needs to make sense of complicated and upsetting stuff using whatever mental tools I have at my disposal. This, I would argue, is what Heart of a Dog is really about. And this is why, I posit, it’s not overly academic or elitist at all to want to watch this film to see true intelligence at work—because it has real, practical use in the personal and emotional lives of everyone who will ever deal with loss, grief, paranoia, or confusion.

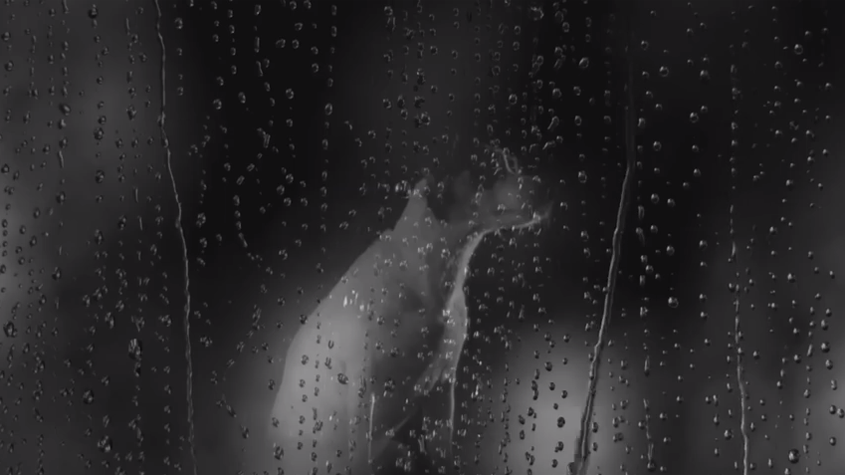

All of this is not even to mention the fact that on a formal level, this documentary is beautifully unorthodox. In the same way that Anderson uses a complex combination of sonic textures in her music and draws together disparate threads of knowledge in the way that she process grief on screen, she also utilizes a vast array of cinematic styles in her filmmaking. Heart of a Dog starts with ink-blotted hand-drawn animation sketched by Anderson herself, but also uses digitally manipulated versions of old celluloid-film home movies, found footage from world news and surveillance cameras, as well as sequences of original cinematography shot from behind rain-covered car windows that is one of the most gorgeous things I’ve seen on film in quite a while. And Laurie Anderson scored this thing! The music is haunting, new age, and like nothing else out there—which you know, if you’ve heard her stuff. So whether you’re a fan of Laurie Anderson’s music, a lover of modern documentaries, a fiend for unique animation and/or cinematography, or just someone who wants to explore some interesting ideas, Heart of a Dog has something for you and I imagine that you’ll walk away from it not somber, but invigorated and inspired.

Heart of a Dog is coming out on Criterion DVD and Blu-Ray in the almost-near future (the date has not been announced yet), but you can watch it on iTunes right now—I give it an enthusiastic recommendation.