Retro Review by Andrew Swafford

A long, unbroken tracking shot follows a bundled-up jogger, clad in funeral black from head to toe through a snowy Central Park. He seems adept and confident, until suddenly, his silhouette is consumed by the shadow created by the overpass of a walking bridge—he faints, quickly dying. Ten years later. An old-money-aristocrat, Nicole Kidman, is this man’s still-grieving widow, and she’s getting remarried to a smug charmer who takes pride in the way he has coerced her into their current relationship over the span of many years. The next day, a 10-year-old boy with a distant stare and a shabby coat turns up uninvited in Kidman’s meticulously designed penthouse apartment. He tells her he is her husband—reincarnated—and that she should under no circumstances remarry. At first, the idea seems preposterous to Kidman and the sure-to-be-Ivy-League-educated socialites who make up her immediate family—but this kid knows way too much about the intimate minutia of Kidman’s former relationship to just be making it up…what’s going on here?

Set up masterfully in a period of 10-15 minutes by Jonathan Glazer (director of 2014’s Under the Skin), this is the premise of Birth, a film that has been sadly overlooked and underappreciated by cinephiles for the last 10 years since its release. The remaining 1.5 hours of this film are tense negotiations and interrogations between this spacey lower-class child and numerous super-wealthy and super-angry adults—and it’s a gripping exploration of grief, commitment, and faith, all set before a profoundly beige backdrop of the modern New York aristocracy and to the tune of (frequent Wes Anderson collaborator) Alexandre Desplat’s ornate orchestrations.

Critics were quick to sing the praises of Glazer’s breakout film Under the Skin for its deliberate pace, its stunning visuals, and its unorthodox story (it’s some type of uncomfortably erotic sci-fi horror film with an art-house sensibility), and he was even deemed “the heir to Kubrick” by a critic blurbed in the trailer. When I—one of those movie fans who practically worships the guy—read this, I was skeptical. But it’s really an astute comparison. While the term “Kubrickian” has really become a shorthand to identify directors who utilize Kubrick’s beloved one-point-perspective shot (which has even gotten the jaunty Wes Anderson a couple “Kubrickian” nods), Kubrick’s style was made up of a lot of different factors. Two that Glazer seems to be inheriting ownership of is experimental usage of orchestral music for visceral effect and an intense focus on setting/mies-en-scene to tell a story. These two things are clearly apparent in Under the Skin, but I haven’t seen anybody digging into Glazer’s back catalog to find Birth, which has all of the same strengths.

In regards to music, Under the Skin features a hair-raising score by Mica Levy that is essentially a chopped and screwed arrangement of orchestral music that fits somewhere between Bernard Herman’s intense and stabby Psycho violins and one of Mozart’s requiems. When the music is at its most organic (and also its most horrifying), Johannson’s alien succubus character is inhabiting the city; when it’s at its most synthesized (and warmly lulling), she’s in the Scottish wilderness—it’s an odd reversal of your usual auditory-association in terms of rural/urban life.

In Birth, music plays up the story’s ambiguity. I re-watched this film with friends last night and had frequent disagreements about the tone of Desplat’s score—I found it ominous, foreboding, and haunting, but they heard it as almost inappropriately cheerful. At the time, I was frustrated, but I later realized that the true brilliance of this score is the way it seems to float to-and-fro across that mental line that you probably don’t even know your brain has between menacing audio cues and reassuring ones. This ambiguous tone is perfect for the narrative of Birth, in which the possibility of a spectral presence in the form of this young boy is always an open question. When the film is hitting its climax of uncertainty, Desplat even makes use of a low but clearly audible whirring sound not unlike the vibration of a cell phone—something so neutral but also so out of place that the audience has no idea what to do with it.

To comment on setting in Glazer’s recent films—Under the Skin uses a three-point juxtaposition between the grimy streets of Glasgow, a wholly artificial/inexplicable black void that feels impossibly dark, and the chilly comforts of the Scottish wilderness to tell the story of how Scarlett Johannson is metamorphosed from being an aggressive predator to being a sexually awakened lost soul. The story’s three-act-structure truly can’t be separated from its setting, just like 2001: A Space Odyssey needs both prehistoric earth and deep space to tell its story of the evolution of humankind and technology; just like The Shining needs the generations-old mansionlike hotel (referenced in Birth—keep an eye on the doorman) to tell its story about regret and historical trauma.

Just like in the work of Kubrick, setting is integral to Birth, and Glazer establishes with that opening snowy jog/death sequence that he fully intends to explore the space of New York city in winter, with all its dingy earthtones, its dark shadows, and its prestigious interior and exterior architecture. Kidman’s character is experiencing a grief-stricken emotional winter that never seems to end, but she looks forward to the new beginning promised by her wedding in May—despite the fact that she’s emotionally detached in her relationship. In regards to architecture, Kidman seems almost to be a piece of furniture in the penthouse she lives in (almost surely owned by her parents and maybe even their parents before that), seeming to have no life, career, hobbies, or even identity of her own outside of her family’s status and privilege. The perhaps-supernatural element disrupts the statuesque balance of loveless marriage and monetary stasis in this aristocratic home, and Glazer makes sure you’re constantly aware of the baroque designs of this world, to the point where many conversations with the possibly-reincarnated boy involve furniture itself—what sofas he and his wife had sex on in their past life, what desk he used to work at, etc. (Again, I have to describe the aesthetic of this film as profoundly beige—its dullness softly emanates off of every frame, just as uncanny yellowness permeated the world of Denis Villenueve’s fabulist thriller Enemy in 2014.)

Despite the amazing ears and eyes for style in the directorial work of Jonathan Glazer, I can’t wrap things up without writing about Nicole Kidman, who owns this film in the same way that Johannson owns Under the Skin. Her performance here is absolutely stellar, and seems to be of a piece with many of her roles in the way the script explores concepts of feminine domesticity as potentially confining traps. There are a number of roles in Kidman’s filmography that touch on this, including: (A) Kubrick’s own psychosexual drama Eyes Wide Shut, (B) the underrated haunted-house film The Others, (C) the Virginia Woolf adaptation The Hours, (D) a second adaptation of 2nd-wave Feminism’s central fiction The Stepford Wives, and then later (E) Park Chan-Wook’s Stoker, by turns both Shakespearian and Faulkneresque in its dark look at incest and sexual awakening in the American South. In all of these films, Kidman is playing some strange spin on the idealized housewife as mythologized by the patronizing commercials of the 50s and 60s.

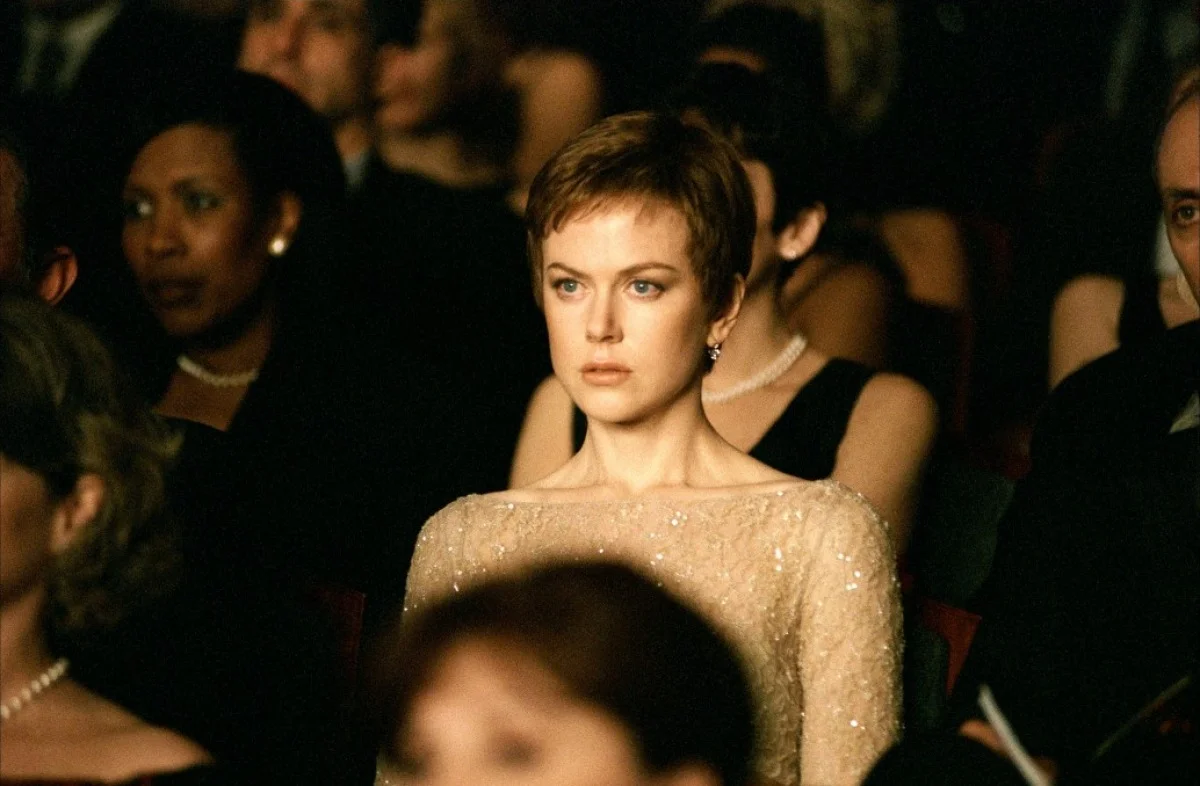

In Birth, the spin is that the housewife’s reason for living—making and maintaining a home for her husband and children—is shattered by unexpected death and ever-lingering grief. Kidman’s performance is one of a broken woman who had no identity to begin with, and searches for fulfillment through another marriage in futility, never self-aware enough to understand the full extent of her own emotional turmoil. There are two breathtaking acting moments in Birth, and they’re both from Kidman. In the first, she has just sat down to watch an orchestral performance after witnessing her 10-year-old-possibly-husband faint from pure heartbreak. We never see the orchestra, because the entirety of the theater scene consists of an unbroken shot of Kidman’s face—it zooms in early and stays there. As the music swells with intensity, Kidman’s stony gaze gradually with suppressed emotion, and she never quite breaks into tears, but the subtleties of the expression express so much that she doesn’t need to, especially thanks to the time allowed by Glazer’s patient camerawork. The second breathtaking acting moment is the final scene, which involves Kidman on a beach during a particularly chilly Northeastern May wedding, channeling the emotional complexity of Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness feminist novel To the Lighthouse. But I can’t spoil it—go watch Birth. Not enough people have.