Review by Zach Dennis and Andrew Swafford

Andrew: Wavelengths avant-garde shorts have been a highlight of attending TIFF for the past few years, and this program (offered virtually so that I could watch while being stranded in Tennessee!) was no exception. I was astounded by the new work presented by familiar names Michael Robinson and Peter Tscherkassky and fascinated by filmmakers who hadn’t been on my radar before, especially Daïchi Saïto and Kim Min-jung.

Taken together, one thing I found surprising about this set of shorts was the unusual amount of text and narration that accompanied the image and sound, and I imagine that was one of the program’s unifying ideas, alongside the idea of presentness and pastness evoked by its title. Two years back, I noted that Sky Hopinka’s Fainting Spells did some really interesting things with scrolling text on the top and bottom of the frame that ended up feeling like sprockets running across a film strip, and I feel that similar games were being played with words here in a film form more commonly associated with silence.

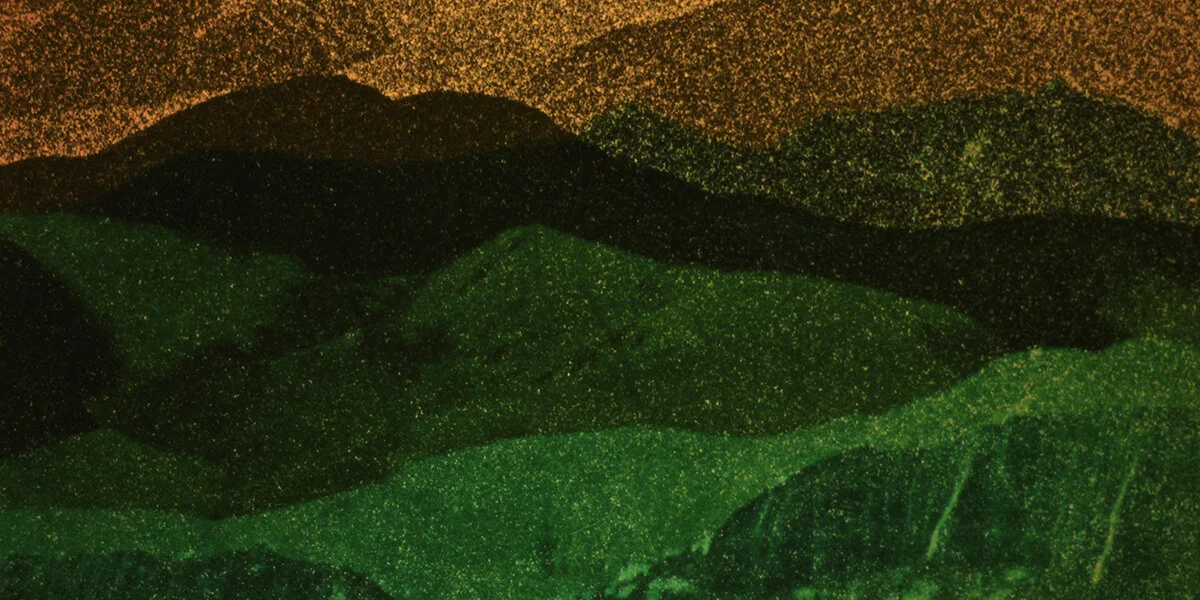

‘earthearthearth’ by Daïchi Saïto

Two films in the program, Nicolás Pereda’s Dear Chantal and Kim Min-jung’s The Red Filter Is Withdrawn., were both constructed around written texts associated with famous experimental filmmakers.

Pereda’s film, which visually consisted of Pereda herself decorating and cleaning up a stylish loft, was accompanied by a reading of letters penned to the Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman as she prepared to rent an apartment from someone who was not-so-subtly enamoured with her work. The decision to include these narrated letters, and to only include Chantal’s incoming letters, will read to Akerman fans as an obvious reference to News From Home, which is carried by letters Akerman recieved from her mother while living in New York. This connection of three dots – from Akerman’s mother, to Akerman’s temporary leaser, to Pereda’s own experience of nesting – makes for a tender, communal rumination on the spaces we temporarily inhabit throughout our lives. I loved the overhead shot of Pereda cleaning fallen leaves off of the sky-light in her ceiling.

Kim Min-jung’s The Red Filter Is Withdrawn., on the other hand, is narrated by a lecture by Hollis Frampton, read in Korean over images of the natural landscape angled to look like frames and windows. In the lecture, Frampton talks about color theory, specifically the false conception that individual colors like red are more colorful than white, which is in reality a combination of all colors and therefore the most brilliant color of all. As Frampton’s lecture develops, Kim plays with the filter on her camera lens, allowing us to see the images with different hues alternatingly added and subtracted. The TIFF-provided synopsis says this short also serves as a commentary on colonialism in South Korea, but I wasn’t quite able to pick up on that layer of the film without more context. For me, it still worked as a wonderful experience for the eyes, and a reminder that we’re always looking through a lens and having our visual experience limited by various frames and filters.

What felt to me like the centerpiece of the program, Michael Robinson’s 23-minute Polycephaly in D, also played with text in an interesting way, as it was framed as a dialogue between two men speaking to one another telepathically across a vast distance of time and space, their exchange only depicted through subtitles. One man wades in a neon-lit pool overlooking a nocturnal cityscape, while the other holds his ear to the ground in a barren mountainous land. This already very strange and intriguing dialogue is grossly overshadowed, however, by the bulk of the film, which is an ever-morphing free-associative montage of footage pulled from seemingly hundreds of media sources. The fact that the film includes footage from the sexually transgressive videos for Cardi B’s “WAP” and Lil Nas X “Montero” would be a footnote in a full catalogue of all the absolutely wild shit going on here – and that catalogue is not something I have a good enough memory to write. I have no idea what Polycephaly in D is about, but I know that every match-cut was inspired and every minute is hysterical in new ways. Michael Robinson is so undeniably fun that he’s one of the few avant-garde filmmakers I believe avant-garde skeptics should be forced to reckon with (which I made happen on our podcast episode on “Avant-Garde for People Who Are Skeptical About Avant-Garde”), and this is one of his most monumentally bonkers works. I hope it becomes available for widespread viewing soon, along with the rest of his catalogue.

‘Polycephaly in D’ by Michael Robinson

I’ll briefly mention the shorts I haven’t paid much attention to here before wrapping up: Vika Kirchenbauer’s The Capacity for Adequate Anger was an interesting, if somewhat droll, confessional piece about her childhood experiences as a queer woman and the anger she reflectively and viscerally experiences/represses as an adult. Laida Lertxundi’s Inner Outer Space is a collection of chapters moving in and out of layered representations of reality: viewing photographs, viewing footage of where those photographs were shot, then seeing that footage projected as an installation piece. Neither one of these shorts spoke to me personally (I thought both could have felt a bit more cohesive), but I could appreciate what they were going for.

I loved, however, the last two shorts of the program, which were surprisingly wordless after all the text-based shorts that had come before. Daïchi Saïto’s earthearthearth is a 30-minute odyssey of psychedelic imagery pieced together by footage of mountainous landscapes and soundtracked by a single jazz fusion piece. 30 minutes is a long time to watch something like this, but I loved the structural arc of this thing: the soundtrack gradually grows more cacophonous as the color grading gradually sinks into a deep red as the images become more chaotic, which struck me as perhaps an attempt to visualize the slow creep of destruction wrought unto to the beauty of the natural landscape due to climate change. By the time it had reached its final stretch, I felt as if the screen in front of me was shaking.

Finally, the program closed with Peter Tscherkassky’s Train Again, a black-and-white montage of train footage found in all sorts of movies, from The General to Johnny Depp’s The Lone Ranger. Far from a supercut or a loose narrative made out of a collection of match cuts like in Michael Robinson’s Polycephaly in D, the images here are stacked atop each other and often feel as though they’re crashing into each other, creating a visceral sense of momentum and movement and even violence. I’m unfamilar with Tscherkassky’s other Train film that this is apparently riffing on, but this film on its own makes a strong case for trains being the ultimate cinematic image, as they are both a symbol of mechanical motion and also run along tracks not unlike celluloid film itself.

Zach: I think you perfectly summarized those early shorts, Andrew. I’d like to just add some to the final shorts you mentioned, which I think were the standouts for me along with Polycephaly in D.

‘Train Again’ by Peter Tscherkassky

You had caught earthearthearth before I had, and so I had your interpretation of the film as an allegory on climate change on my mind as I watched it. I think it’s an apt way to interpret the film as Saïto draws your focus to what feels like the inside of these landscapes rather than focusing on the beauty of the exterior. When climate change is depicted visually, we see a lot of images of pristine beauty, and so it’s an interesting route to take for Saïto to focus on what I’ll describe as “the inside” of these landscapes because their importance to the natural system and how the earth works is more important than the National Geographic photo that is usually propagated to energize outrage over a specific issue.

The real issue with climate change is what it’s doing to the systems that generate life, not an Instagram shot of a national park. I feel like Saïto gets at that point in the film.

As for Train Again, I’m a big supporter of the idea that a train in a movie is perfect cinema. From the Lumière brothers, to The Great Train Robbery and The General, Tscherkassky both evokes that locomotive cinematic history while also tracking it in a way that makes my case.

His choice to overlay images builds this loose narrative of connectivity between these images through time, displaying that connection within film history of the train from the earliest days of film to something more recent like Unstoppable. There’s a consistency to this machine in movies — which is a nice parallel to the function of the train as a reliable transportation device.

I’m also unfamiliar with his other Train film, and would be curious to see the two in tandem.