By Zach Dennis, Andrew Swafford, Jessica Carr, Lydia Creech and Nathan Smith

**NOTE** This is not in ranked order

Mr. Roosevelt (2017) by Noël Wells

I HATE the word quirky, and I really HATE when people call me quirky. I’ve heard it all from, “Your dress is so quirky” to “You are just so quirky.” This hate for a single word is why when I saw the lake scene in Mr. Roosevelt I related to it so much that I watched it at least 2 more times. The scene shows Emily played by Noël Wells talking to a guy she just met at the lake. The exchange goes like this:

Art: You have the whole quirky-girl vibe going.

Emily: Oh, jesus. That's so condescending.

Art: Saying you're quirky is like saying you're interesting. It's a compliment.

Emily: No it's not because you'd never call a guy that. You'd use another word like eccentric, but with a girl you need a word that recognizes her uniqueness but at the same time devalues her intelligence.

The exchange continues with a more light-hearted tone, but I think our buddy Art got the message anyway. This conversation is really what set Mr. Roosevelt apart from the other comedies I’ve seen this year. With her debut feature, Noël Wells isn’t afraid to make sure her audience knows they aren’t getting a movie about a Manic Pixie Dream Girl. In fact, there is nothing “quirky” about Mr. Roosevelt’s lead character at all. This movie is a good example of what happens when we let the misguided girl tell her own story.

The indie film follows Emily, a struggling comedian based in LA, as she goes home to Austin when a member of her family becomes ill. She has barely a penny to her name so she is forced into an awkward situation where she stays at her ex-boyfriend’s home with his current girlfriend. Much like most movies about young twenty-somethings trying to find their way Mr. Roosevelt’s plot kind of floats around like it’s protagonist, but I found myself connecting with Emily’s character. It’s amazing to watch a female-centric comedy that isn’t focused on a romantic relationship. Noël Wells writes and directs a film that is by no means perfect, but the script is genuinely funny and thoughtful. I hope this film marks a moment where the quirky girl dies and is replaced with someone like Emily instead. - Jessica Carr

DOUBLE FEATURE: The Little Hours (2017) by Jeff Baena // Ingrid Goes West (2017) by Matt Spicer

Please ignore the dudes credited as directors; both of these films belong to Aubrey Plaza. The actor produced both films (her first production credits outside of television), and both scripts seem written especially for Plaza’s nihilistic-beyond-her-years comedic persona.

Despite not receiving much spotlight for her over-the-top brooding otherwise, The Little Hours and Ingrid Goes West prove that Plaza can carry a comedy almost single-handedly — and her unique presence opens doors for much-needed new (and tightly-scripted!) stories in a relatively stale movie genre. Displaced in time by over 600 years, these movies depict different worlds, yet similar experiences of young people scrambling for meaning.

In the medieval farce The Little Hours, Plaza is a nun--not because she wants to be, but seemingly because she has no other option, with the convent serving as the 14th century equivalent of boarding school. In true schoolkid fashion, Plaza looks for any and all ways to shirk responsibility and sneak misbehavior. With no other model available, the most logical option for a disillusioned young nun is outright rebellion--swearing and drinking and screwing and dancing naked in the woods--and its medieval context adds a lot of thematic richness to otherwise familiar low-brow comedy. (I wrote about it in-depth here.)

Ingrid Goes West, on the other hand, is a dive into the deep end of 21st century soul-searching--the arena for which is, of course, social media. Here Plaza plays Ingrid, a bitter young woman who loses her only face-to-face relationship in the film’s opening when her mother dies of terminal illness. With nowhere else to turn, Instagram becomes Ingrid’s window into a happier world, suggesting that these perfectly photographed and carefully curated lives of others are much more fulfilling than her own. It’s a morbid premise, and the rest of the film plays out as a satire of social media obsession that escalates to a twisted, Twilight Zone-esque ending.

Crucially, the film isn’t just a screed about youths spending too much time on their phones; it’s an an empathetic portrait of the obsession’s root causes. Ingrid’s loneliness and alienation seems, to me, not so dissimilar from the tedium and unfulfillment that the swearing nuns of Little Hours embody--and Plaza is just about the only comedic actor capable of (or interested in) making us laugh at such universal human maladies. — Andrew Swafford

The Trip to Spain (2017) by Michael Winterbottom

Two British men are tasked with travelling to a lavish location in order to “review” food from decadent restaurants. Along the way, they laugh, drink and sing, but more importantly, they mock, bicker and impersonate (other celebrities, not themselves).

It may seem toxic. It may seem harsh, but overall, it really is just a friendship.

This is core to The Trip to Spain, the latest in a trilogy of films pitting fictionalized versions of comedian Rob Brydon and Steve Coogan against one another. The two men are undoubtedly friends, but that friendship lacks the lightness or openness that typical comedies portray. Coogan and Brydon are generally at odds — competing cheekily to take the next stab at one another, not on their dinner plates but in the others’ gut.

This constant ribbing is rather charming. It contains a large degree of self-loathing but has this air of superiority (especially with Coogan) that makes the blows against Brydon pointed, but ultimately, sad. In the first movie, Coogan wants more: from his girlfriend, from his son and from his career. Parallel that with Brydon’s life at that moment — a new father, who is blissfully in the pains of early parenthood with a happy wife.

The tables turn in the second leg. This time Brydon is unhappy — questioning his standing both in his profession and in his family while Coogan reaps the benefits of a healthy career boost (due to a new American television series) and an interest by his son to spend time with him.

The third film lacks as much ground to cover as one or two, instead, leaving both men in a limbo. Spain seems more narratively audacious than its predecessors and that may derive from the risks each man is looking to take as the plot moves along. Ultimately one takes the plunge while the other adheres to old conventions, but the trip itself is just as satisfying as it ever has been — if not even more. — Zach Dennis

The Boss Baby (2017) by Tom McGrath

The output of DreamWorks Animation Studios is not my typical domain as a moviegoer; the world of children’s animation in general is far from my wheelhouse. But, in the weeks preceding its release, as it became enshrined among meme classics like Minions and CHAPPiE, I decided that it was my duty as devoted defender of all that is cinematically discarded, disregarded, and downright disreputable to give Tom McGrath’s The Boss Baby an honest shake before employing or apotheosizing it as a perpetual punchline.

To my surprise, The Boss Baby was, at the very least, one of the most singular cinematic experiences I had in 2017. Its story of an older brother who grows paranoid at the thought of an infant intruder penetrating his perfect bubble of parental adoration and domestic bliss plays closer to Eraserhead, Rosemary’s Baby, or Jaume Collet-Serra’s Orphan – for my money, three of the best American films about the anxieties of expectancy – than what’s normally deemed acceptable for the eyes of children.

This isn’t a new phenomenon: many of the most timeless works of children’s animation, from those of Frank Tashlin and Chuck Jones to Gremlins and Toy Story, straddle a delicate divide between fantasy and horror, delighting and disturbing at once. Lord knows that if Alec Baldwin’s voice came out of a real baby à la Look Who’s Talking, the obstetrician would slap him with an R-rating across the brow before he’d slap him on the bottom. Cinema doesn’t have a monopoly on violent or disturbing children’s entertainment, which has existed in every form from Punch and Judy shows to the “automated hellscape” of animated YouTube videos aimed at absent-minded kids.

Why is it, then, across centuries and specific cultural contexts, that we feed our children violence more often than we feed them their vitamins? What we see on screen is, of course, vital to our development, but maybe we’ve been framing the conversation wrong. Violent images, as we’re all too often aware, can numb our capacity for empathy and understanding, but the alternative isn’t desirable; swathing the eyes of our babies and sealing the door doesn’t do them much help either. Long after children develop object permanence, they maintain an unstable and slippery view of the world around them. Boundary-pushing animation like, Duck Amuck, Dante’s Small Soldiers, and yes, The Boss Baby is an elastic band, stretching not only our eyes and imaginations into our shape, but our understanding of reality, working out those impulses and urges that physics forbid our own muscles from following through on. Cinematic violence, when appropriately detached from realism, allows us not emotional catharsis, as is often considered the case, but a physical workout.

The Boss Baby, then, is a Rube Goldberg-designed Stairmaster with talcum powder sprinkled on top, more complicated, colorful, and cartoony than any animated films I’ve seen in years. Even when it leans into Pixar-ish sentimentality, The Boss Baby remains a dark trip into the child’s unconscious mind, where fantasy and horror are opposite sides of the same dime. Anti-realist movies like The Boss Baby redefine violence, no longer a weapon of oppression but a portal to a world where gravity is the boss of no man, woman, or baby. — Nathan Smith

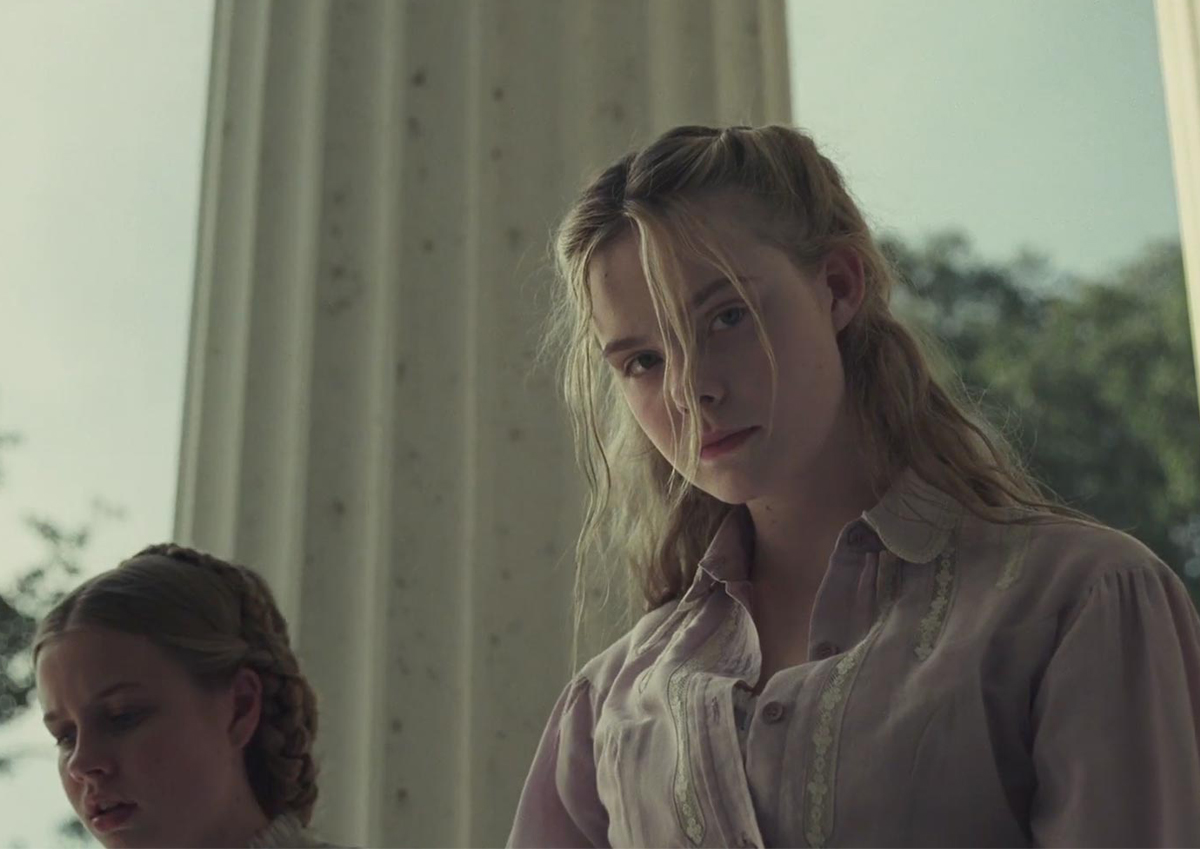

The Beguiled (2017) by Sofia Coppola

Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled is a romantic comedy. I’m not quite sure what Don Siegel’s 1971 original is (Western? Exploitation film?) aside from really good in a randy, feverish way — but Coppola’s is decidedly more of a polite will-they-won’t-they full of stifled laughter and awkward silences between people who clearly have a thing for each other.

Just a few years into the civil war, Corporal John McBurney is a Union soldier who has been injured in battle and given hospitality by a schoolhouse full of lonely Confederate women who would have to give him up to the authorities if he weren’t so handsome. In the 1971 film, McBurney is played by a grizzled Clint Eastwood, who sees the house as a harem to salivate over; the film, more or less, shares that view.

Coppola’s version doesn’t change McBurney’s core nature, but casts Colin Farrell as a comparatively clean-cut “nice guy,” creating an ironic contrast between his squeaky-clean exterior and his indulgent intentions. But Coppola also crucially changes the film’s central perspective--not completely from the male gaze to the female one, but rather to the space of comedic tension in-between. We’re presented with three different women (Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst, and Elle Fanning) who all have eyes for McBurney and unique chemistry with him, and we’re implicitly invited to ship one (or all?) of these equally unhealthy relationships for the bulk of the film.

Before violence erupts in the film’s final act, The Beguiled plays with slow comedy, which is not so much concerned with a succession of funny moments as it is with just calmly enjoying being in a funny situation. Look at the first dinner scene, which is awkwardly hushed with anticipation of romance. Every character choice is loaded with barely-hidden courtship: when McBurney praises the apple pie, one woman draws attention to herself with “I love apple pie,” another woman takes credit for the recipe, and another reminds the table that she picked the apples.

There are few punchlines and no pratfalls, but every sly stolen glance, flirtatious innuendo, and peacocking wardrobe decision on the part of the women screams thirsty AF in a way that is subtly hilarious. — Andrew Swafford

The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017) by Yorgos Lanthimos

I’ve seen several reviews refer to Lanthimos’s newest film, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, as a horror movie, but I think many critics are overlooking that it’s pretty funny, too. I mean, yes, the set-up — Colin Farrell’s family is struck with an illness that causes paralysis and death and the only way to stop it is if he chooses to kill one of them--certainly doesn’t sound rife with comedic possibility, but believe me, I laughed out loud several times over the rundown to the inevitable conclusion (uh, not just me! There were other laughers, too).

Laughter is often a surprise response to unexpected juxtapositions of situation or tone, which is something Lanthimos is famous for. Maybe it didn’t work for everyone, but the combination of the stilted line delivery with what should be pretty emotional moments (“Daaaad! Bob’s dying!”) often got me good. I also tend to have an affinity for pretty cruel humor (When it’s punching up! (Mostly!)), and the incompetent way Farrell’s character attempts to worm out responsibility struck me as supposed to be funny.

The justice being meted out to him is rooted in Old Testament, patriarchal ideas (yeah, I know, Greek mythology, whatever), where children pay for the sins of their fathers.

Similar to mother!’s "men are trash" takeaway, The Killing of a Sacred Deer satirizes men who think they can control everything and that everything revolves around them. For Farrell’s character, it IS a horror film; for his wife and kids, they just resolutely adjust to a new (but maybe not even worse, really) reality. Women and children are historically always the victims of lessons meant for men. My in to Lanthimos’s satirical intent was Kidman’s performance. Though maybe not given enough to do, I thought she was the only one asking the right questions or trying to do anything. If it had been up to her, I think she’d have had no problem making a quick decision. And, fitting right into the “metaphor,” it doesn’t matter and she knows it and the audience knows it. Kidman’s icy calm to her husband’s fuck-ups seems like the only reaction to a game that she’s somehow in but can’t play.

Sometimes the humor isn’t laugh out loud, but the thin-lipped recognition of “oh that feels true” even in the face of absurdity. — Lydia Creech

The Big Sick (2017) by Michael Showalter

By the time 2017 rolled around, I think a lot of people were getting tired of the standard formula for romantic comedies. Guy meets girl. Girl falls for guy. Some laughs are thrown in and your average rom-com is born.

This year, however, comedian Kumail Nanjiani and former therapist turned writer Emily V. Gordon shared their real life love story with the film, The Big Sick. Kumail plays himself in the movie and Zoe Kazan steps in as a surrogate for Emily. The genre is given new life with this delightfully charming look at how even when all odds are against your relationship there is some small glimmer of hope that things will actually work out.

The film shows Kumail and Emily as they begin dating. As they start to fall for each other, things get complicated when Emily finds out Kumail’s traditional Muslim parents want him to have an arranged marriage. Shortly after they break up Emily becomes ill and has to be put into a medically induced coma. From that point, we are are getting the story from Kumail’s perspective as he bonds with Emily’s parents while visiting the hospital each day.

If anything can be gained from the film, it’s a better understanding of how relationships function in the real world. It does a good job of showing how cultural barriers can affect people. The climax of the film shows a heartbreaking confrontation between Kumail and his parents when they find out he is in love with Emily and he’s been hiding it from them. Still even in the darker moments, the movie manages to keep a consistent comedic tone thanks to Kumail’s performance and his passionate love for cheese.

All in all, The Big Sick made me laugh, cry and more importantly made me believe rom-coms could be good again. — Jessica Carr

Logan Lucky (2017) by Steven Soderbergh

There’s a quality of comedy built on the sense of unsteadiness.

It was much more physically realized in the age of silent films with the likes of Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton shifting two and fro with comical ease, but it can also work in a more narrative sense. Maybe it doesn’t, but really, I just needed to introduce Logan Lucky.

People questioned why Steven Soderbergh would jump out of self-imposed exile to make a low-key caper that was interested in moving plots, multiple storylines and a focus on the capital-D, capital-S deep south of West Virginia and North Carolina. Sure, it may lack the pedigree that most would expect from a break from retirement, but it doesn’t lack the substance.

The film follows the Logan brothers (played by Channing Tatum and Adam Driver), who decide to rob the Charlotte Motor Speedway during its prime NASCAR race of the year. They enlist the help of their sister, played by Riley Keough, as well Joe Bang (Daniel Craig), an incarcerated pyro-fanatic who may enjoy eating a hard-boiled egg in a West Virginia prison, but is still able to flash a smile that looks distinctly like James Bond.

Soderbergh has used Tatum in such an interesting way since the two first collaborated on Magic Mike, zeroing in on his working man personality rather than the drop-dead gorgeous leading man he played in the Step Up movies or the caricatured pretty boy he re-invented himself with in 21 Jump Street.

Soderbergh also lacks any interest in applauding the humanizing qualities of Tatum’s characters, but rather he aims to generalize them. This act of rejecting the idea of “tearing down” the movie star persona of his leading man, but rather honing in on the most trivial aspects of the character not only highlights the actor’s ability to convey personality through facial expressions, tone inflections and movement but also creates someone more memorable.

This tactic works again and again in Logan Lucky from Tatum to Driver to Craig to finally Seth MacFarlane doing his best Richard Branson impression (h/t Nathan). It may not be among Soderbergh’s pantheon, but it was a film that was fun and looked fun, and at the end of the day, that’s all anyone fucking wants. – Zach Dennis

Girls Trip (2017) by Malcolm D. Lee

There’s not much left to add to the critical conversation around Girls Trip, the feel-good-hit-of-the-summer that no list of 2017 comedies is complete without including. The film sees four college friends (the self-proclaimed “flossy-posse”) reunite for a trip to the New Orleans Essence Festival after many years of growing apart.

More important than the plot are the names involved: for Girls Trip, director Malcolm D. Lee (cousin of Spike) created a fantastic lead role for Regina Hall, reunited Set It Off co-stars Queen Latifah and Jada Pinkett Smith while properly introducing the world to the firecracker talent of Tiffany Haddish. This is the rare mainstream improv-heavy hangout comedy that actually works (apologies to Seth Rogen) almost solely on the strength of its personalities.

All are outshined, though, by the sheer exuberance of Tiffany Haddish, who is an uproarious cyclone of nastiness (in a very good way) at pretty much all times. Thanks largely to her talent, the film is unequivocally, in the words of Nathan Smith, “a blast in a glass.”

If there is any justice in the universe (and hey, probably not), the Oscars will nominate Haddish for Best Supporting Actress, award her Best Supporting Actress, and let her give a speech like the one she gave at the New York Film Critics Circle, which was 18 minutes of free-form, highly-explicit reflections on childhood and superstardom (“[I’m proud] to be able to be this example to so many youth—there’s so many people like me that you guys have no clue about. But they coming. Because I kicked the fuckin door open.”).

And that last part about her being able to speak her sure-to-be-expletive-laced piece at the Oscars is not a joke: what I admire about Haddish more than anything else is her complete and utter disregard of any expectations of “formal” (read: white, upper-class) decorum or “proper” (read: white, upper-class) language usage. Most black public figures, once they’ve reached a certain level of societal visibility, scrub any trace of African-American Vernacular English (AAVE: which has its own distinct system of grammatical forms/rules) from their speech, instead code-switching into the language of power and money in order to appeal to a broad audience and avoid being judged by the (consciously or unconsciously) racist eyes of the world. Tiffany Haddish doesn’t give a fuck about that; she is the queen of AAVE on the world stage.

No one else with Haddish’s visibility speaks like her with such enthusiasm and power--and kids who speak her language need to see her wear it as a badge of honor rather than a barrier to their success. Pass Haddish the mic. -- Andrew Swafford