By Jessica Carr, Andrew Swafford, Lydia Creech and John McAmis

Note: These films are not ranked by quality, but rather in chronological order

Double Feature: Night on the Galactic Railroad (1984) by Gisaburō Sugii // Angel’s Egg (1984) by Mamoru Oshii

The wisdom of Pixar’s Brad Bird suggests that animation isn’t a genre, but a medium. Unfortunately, the two cultural titans of animated film--the United States and Japan--seem hell bent on telling the same types of stories over and over. In America, animation tends to be reserved for children’s stories of anthropomorphized animals and fairy tale adaptations. In Japan, animation tends to fit the conventions of certain fanservice-y subgenres: mecha, magical girl, monster hunting, teen romance, fantasy combat, etc. These storytelling tropes may feel firmly established and canonized now, but it’s fascinating to go back to the early days of anime cinema (pre-Totoro, pre-Akira), when creators were still imagining what the new form would become, considering the infinite possibilities only afforded by a medium which requires every detail of the world to be constructed from the ground up. Night on the Galactic Railroad and Angel’s Egg are perfect companion pieces in this respect. Both released in 1984, these films are morbid little metaphysical mood pieces that seem apropos of nothing but end up being infinitely interesting.

Galactic Railroad is an adaptation of a popular Japanese philosophical novel for young adults about two schoolboys who take a fantastical train into the stars. The filmmakers have slightly transmorgified the premise, setting the story in a world of anthropomorphized cats because reasons. It is at once talky and full of surreal imagery, consisting of strange, episodic encounters with magically (dis)appearing passengers who often speak in non-sequiturs and do impossible things. Watch Galactic Railroad with your trusty astronomy textbook, Christian Bible, and Esperanto dictionary handy if you want to unravel the densely packed, strange logic of the film--or just absorb it as a hypnotic, uncanny, spiritual experience that stands in stark contrast to Western storytelling.

Angel’s Egg, on the other hand is a spare, silent, and static film. Its central characters are a young girl protecting an egg and a man keeping watch over her in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, but director Mamoru Oshii (of Ghost in the Shell fame) tells their story primarily through gothic architecture and imposing gloom rather than plot or action. If you, like me, were turned to stone by the way Oshii’s OG Ghost in the Shell talks at you, watch this--it’s pure visual storytelling. Like Galactic Railroad, Oshii’s film has it’s fair share of inexplicable action; my favorite moments are the most uneventful, though, with top honors going to a 2.5 minute shot of a fire slowly going out, accompanied by choir vocalizing. Angel’s Egg feels like the anime equivalent of Slow Cinema, along the lines of Denis, Weerasethakul, Ackerman, and other directors known for their Zen-like patience.

Looking at Angel’s and Galactic Railroad from a modern perspective, one can’t help but wonder what spaces the genre could have explored if this type of storytelling had caught on in the same way that Gundam and Sailor Moon did. - Andrew Swafford

Memories (1995) by Katsuhiro Otomo, Koji Muramoto, and Tensai Okamura

An anthology film in three parts, each about a different sci-fi world and story. Anthology films have always been tricky to approach for me, but I think this one is particularly strong in that all the episodes work together and apart. I actually first heard about this film when doing a deep dive on Satoshi Kon, who was the writer on the first episode in this film, "Magnetic Rose" (Koji Morimoto directed). I’ve talked about Kon before, and even in this early project, the themes that will concern the rest of his career emerge. "Magnetic Rose" jumps right into the heady topic of memory v reality, all wrapped in a Gothic ghost story (in space!). The second episode, "Stink Bomb," isn’t my favorite, but it zips along and provides a bit of relief from the intensity of the last episode (Director Tensai Okamura says he doesn’t want the audience to get “philosophical”).

It also ticks the box for military vehicle porn, which is like a sci-fi anime staple. Even if I don’t care for this one, I see its use as a break, and other people might find the kind of anime comedy in it amusing. The final episode, "Cannon Fodder," is directed by Otomo and, despite my love for Kon, my favorite. It actually does the kind of gimmicky thing of the illusion of one-take, but I feel like it’s animation so forgivable (YMMV)? "Cannon Fodder" is incredible, both in terms of aesthetic and world-building, and I don’t think I’ve seen any anime quite like it before or since. This episode basically seals the deal on Memories for me.

So, if all three episodes are so different from one another, what makes it work as a whole? I think there’s really something special about the medium of anime and the genre sci-fi, and the title Otomo chose points to a quality all the episodes share and what makes Memories work as an anime film. Memories uses anime to marry this ability to bring the world of tomorrow into the now of today (but also it’s got that 90’s anime video aesthetic that traps it a nostalgic past) and a general cultural anxiety about scientific progress. Each episode deals with fear of a different technology/science, but they’re all facets of the same feeling, a foregone conclusion on fantastical scenarios. I tend to think anime (and manga) are best when they’re one-off shorts (self-containment is everything), and Memories presents three really good ones. - Lydia Creech

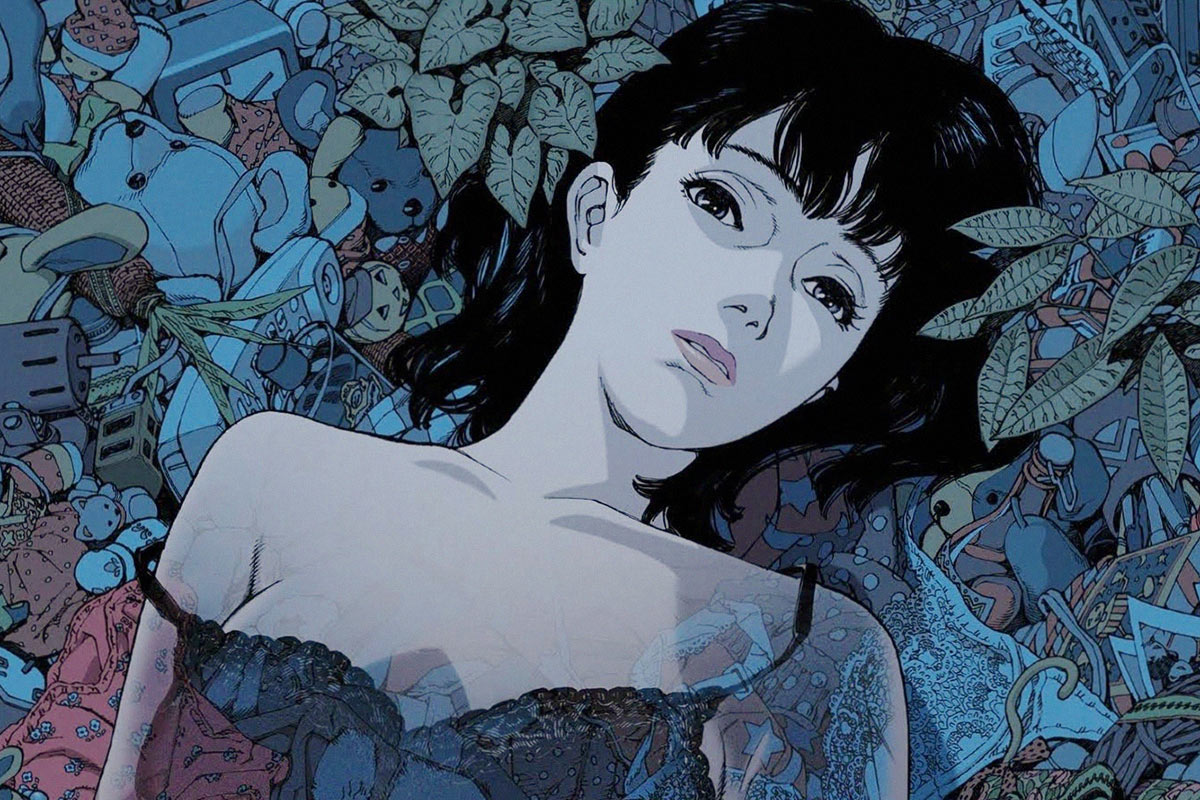

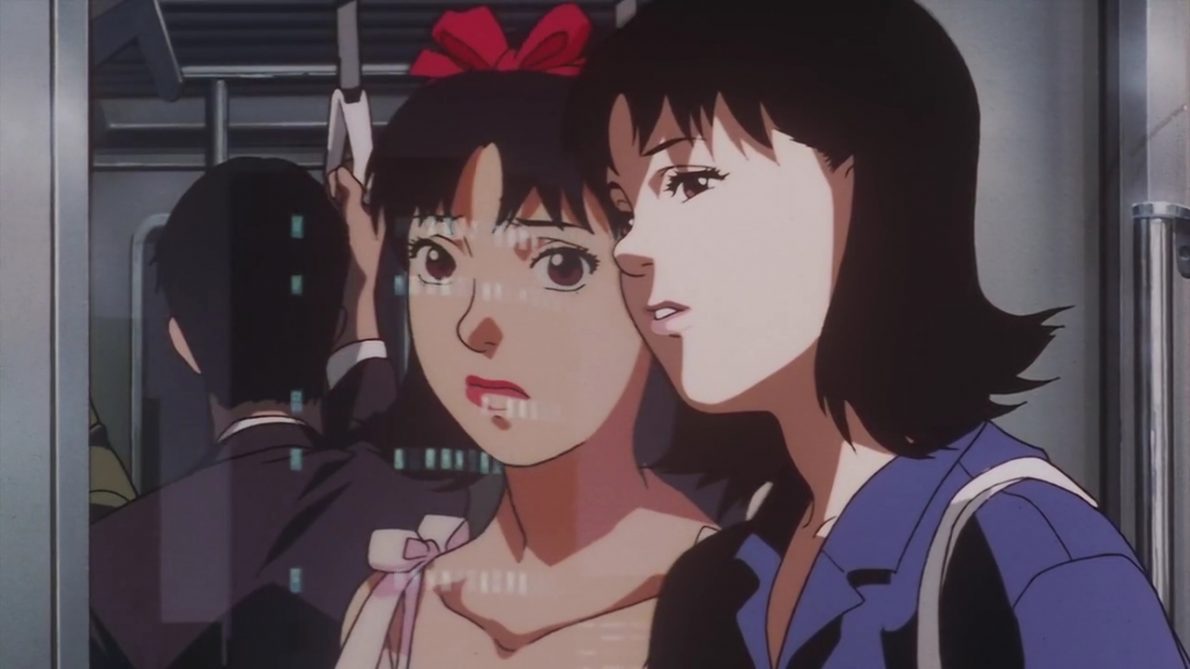

Perfect Blue (1997) by Satoshi Kon

One needn’t be an anime aficionado to recognize its woman problem--or rather, it’s man one. With the infantilization of women and the objectification of young girls as a basic genre convention (as well as how rape-y its representations of sex can be), a particular type of power-hungry male gaze has become hard-wired into the code of anime as a systemic, industrial machine. Satoshi Kon takes on the predatory fetishism of anime culture head on with Perfect Blue, using his trademark hyper-modern reality-bending to analyze the ways in which mass media constructs, commodifies, and consumes artificial beauty.

The narrative here follows Mima, an Idol Singer (look it up) who re-negotiates her contract to abandon the her manufactured good girl image and branch out into the film industry--and it’s hard to tell if her film work is porn or not. At the same time, Mima’s privacy (digital and otherwise) is increasingly invaded by a disfigured otaku, who seems to want to take possession of not only Mima’s body, but her identity itself. As the internet and its many personas further creeps in upon and already persona-driven narrative, lines of personhood become blurred, and Mima is caught in a war not only with her obsessive fan, but her own public image. Kon’s world is a world of flat surfaces--computer screens, billboards, videotape, newspapers, windows, and mirrors--and each smooth surface causes some internal fracture within his flesh-and-blood characters, who can’t always reconcile the dissonance.

It’s such a shame that Kon left us when he did--I think often about how sharp of a media critic he was, and how willing he was to incorporate the ever-changing technological landscape into the world of movies. We need him now more than ever. - Andrew Swafford

5 Centimeters Per Second (2007) by Makoto Shinkai

Over the years, Shinkai has slowly been making a name for himself among both anime fans and lovers of independent cinema. Shinkai has been recognized as a leader of auteur anime in Japan, and hailed as the next Hayao Miyazaki. Much different than Miyazaki, though, Shinkai still finds a reliable audience among the Ghibli supporters. 5 Centimeters Per Second is a beautiful gem of an animated film. It's technically a triptych, with three separate stories (episodes) that are thematically similar and serve a singular goal. "Short stories about their distance" is the tagline for Shinkai's film, and an appropriate one, too. Stories of first love, rejection, and crumbling relationships revolve around a central character Takaki, who we follow throughout his childhood, adolescence, and adult life in just sixty minutes.

Contrary to the scope of the film, it's beautifully slow with a contemplative pace. Shinkai's films are always populated with gorgeous scenery, touching voice over, and a very reserved style of animation. His backgrounds (I say "his," but an artist working beneath his direction really created it) are especially breathtaking and detailed pieces of art. He can somehow make a group of school desks seem banal and poetic. His use of light and texture is incredibly realistic -- it almost harkens to constructed sets and live action techniques utilized by stop-frame animation studios. Lights of trains reflect off their rails as they pull into the station. A plume of smoke bisects the sunny sky and creates a shadow on its far side. The animation, like the stories he tells, is very quiet and soft. Extreme gestures seen in most anime simply don't belong in this world, and Shinkai is very particular about how much emotion each character is allowed to share with the audience.

Lastly, unlike most traditional anime films, 5 Centimeters Per Second's main goal isn't entertainment, but empathy, and it's no doubt one of the most empathetic films I've ever seen. - John McAmis

Summer Wars (2009) by Mamoru Hosoda

Despite being partially Asian, I never really liked anime growing up. The reason being mostly because my older brother was obsessed with it and also because the culture (picture the people in high school that were obsessed with anime, you know who I’m talking about) also turned me off. But in college I was introduced to Miyazaki films and my bias started to dwindle a little. Slowly I started to give anime a chance, and the purpose of this canon list is to really highlight other films that weren’t made under Studio Ghibli.

For my first film, I chose Hosoda’s Summer Wars. The film feels like a fun mix between WarGames and Tron. It follows young math genius Kenji as he goes to his crush Natsuki’s house for summer break. To Kenji’s surprise, Natsuki introduces him as her fiancé to her entire family. This becomes kind of a subplot because the real conflict comes from Kenji receiving an email with a mathematical code, which he unknowingly cracks, causing an artificial intelligence ("Love Machine") to hack his avatar in OZ where Kenji is an administrator. OZ is a virtual world with avatars that closely resemble Digimon characters. And as everyone finds out, controlling OZ also gives “Love Machine” the ability to control the outside world including emergency services and nuclear power???

It only escalates from there and the plot gets even more convoluted with complications. But don’t worry about getting too wrapped up in the details, the movie ties most of its loose ends by the conclusion of the film. Instead try and focus on the likeable characters, family values and visual feast that Summer Wars emanates. - Jessica Carr

A Letter to Momo (2011) by Hiroyuki Okiura

A cool breeze rushes over the water surrounding Shio Island where 11-year-old Momo and her mother move after the death of Momo’s father. Away from Tokyo, Momo feels disconnected. She misses her friends and being surrounded by a cityscape. She keeps an unfinished letter from her father that only says, “Dear Momo.” Soon, three Yokai (demons/spirits in Japanese folkore) fall from the sky. The trio goes on a redemptive mission to help Momo and ultimately escape punishment for breaking divine laws.

A Letter to Momo is a heartfelt coming-of-age film that uses nature and Japanese folklore to tell a story of healing. While the Yokai are somewhat grotesque and at times silly characters, they still become an essential part of Momo’s grieving process. You can see the Yokai start to take on a parental role when it comes to Momo. The script for the film is beautifully written, and I definitely teared up quite a few times.

For some viewers, A Letter to Momo might not be the most innovative film, but it shows an inherent understanding of grief that most films can’t achieve. - Jessica Carr