By Zach Dennis, Nathan Smith, Malcolm Baum, Ben Shull, Jessica Carr and Andrew Swafford

Note: These films are not ranked by quality, but rather in chronological order

Juice (1992) by Ernest Dickerson

To have the juice is to have respect, power, and most importantly, machismo. Stereotypically speaking, these are among the most central tenets of hip-hop, which takes braggadocio and swagger as convention, especially regarding physical strength, sexual prowess, and financial independence. To want the juice is to fear not having it, and to flex is to admit a craving for validation. In the world of cinema, there is perhaps no greater exploration of hip-hop culture’s masculinity crisis than Juice, directed by Ernest Dickerson (Director of Photography on most early Spike Lee joints). This boom-bap infused film follows Omar Epps as an aspiring young turntablist named Q who rolls with a crew of Harlem teenagers without much to do other than the performative work of gender. Harassed daily by police and local gangs, the boys feel powerless, scared, and insecure, despite their external cockiness.

Thematically, this is one of the tightest scripts out there. Every line and action of this film, in one way or another, can be traced back to the masculine desire for respect through any avenue possible: name-brand shoes, dominance over women, and competition in all forms (the pool hall, the arcade, the DJ booth, etc.). And although Dickerson’s film has great sympathy for the boys, it doesn’t come without a heavy acknowledgement of power’s dark side. Inevitably, the desire to control one’s own life leads to violent intimidation when Q’s friend Bishop (played by Tupac Shakur) obtains a handgun, which unsettles Q profoundly. Not since Richard Wright’s “The Man Who Was Almost a Man” or Matthieu Kassovitz’s La Haine has a single firearm carried so much weight; it’s presence in each scene is overwhelming and genuinely terrifying. The gun seems to own Bishop like Tolkien's Ring of Power, and Tupac plays the role with desperation and fervor. The casting here is a genius reversal, as Shakur has become famous for being one of the first rappers to wear his vulnerability and sadness proudly (see “Shed So Many Tears,” “Dear Mama,” and the posthumous poetry collection The Rose That Grew From Concrete). For those familiar with his musical output, it’s impossible to view this villainous character without sympathy for his internal fear and insecurity.

(And as a rap-bonus, Juice has a supporting role from Queen Latifah, who at the time was known more for her afro-feminist musical output than her acting work.) - Andrew Swafford

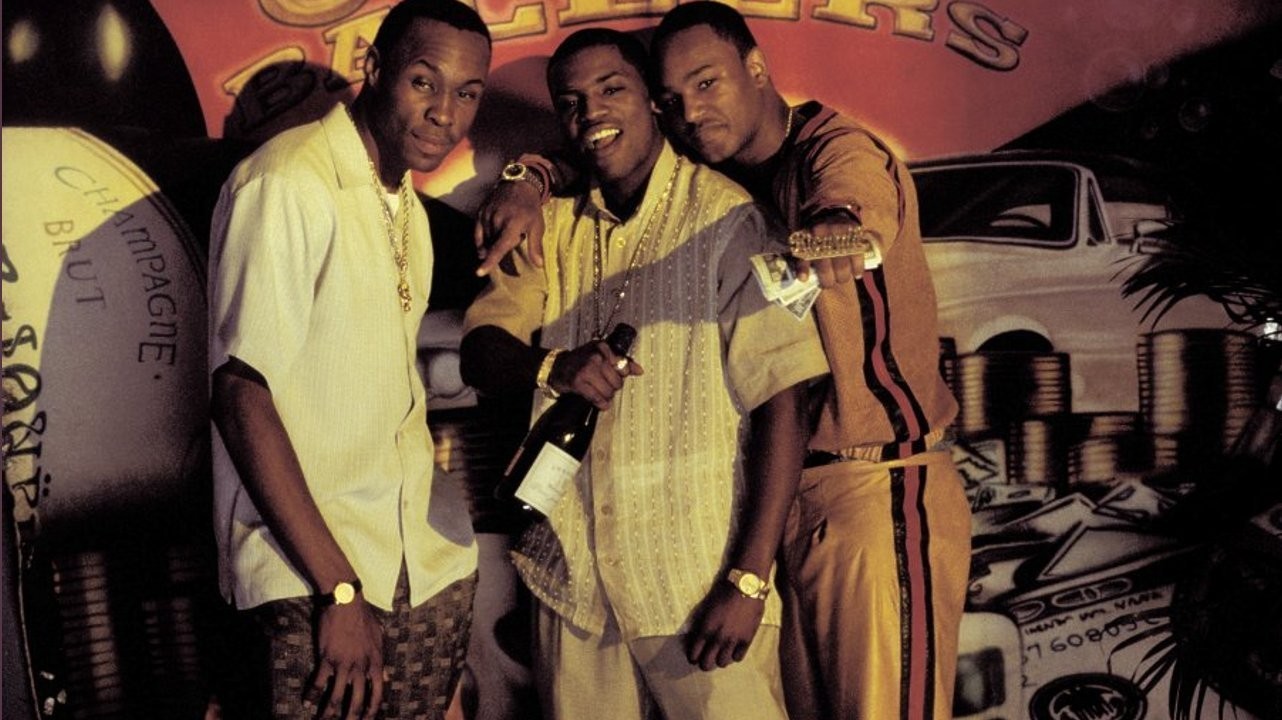

Belly (1998) by Hype Williams

Even if Belly came out today, it would feel like a product of the future. Evidence enough can be found in the stunning opening sequence (go ahead and watch it if you haven’t): a high-contrast, slow-motion club scene lit in deep-blue neon strobe lights overlaid with acapella backup vocals from Soul II Soul’s “Back to Life,” all edited with enough free-association to feel like a lucid dream. The scene is so vividly electrifying that desire for conventional context (character, plot, theme, etc.) falls away--the aesthetic experience is enough. The actual story, once established, is a conventional one about men in the drug trade--played here by rappers such as DMX, Method Man, and Nas (who carries himeself with a monk-like center of gravity)--getting in over their heads, but it ultimately doesn’t matter.

Known primarily for directing dozens upon dozens of music videos, director Hype Williams is a stylist through and through, and he seems to approach each familiar scene as a challenge of light and color. How can a traditional negotiation scene be made evocative again? Williams plays with smoke, television reflections, and double-exposure to solve that problem, among countless others. Belly innovates on a minute-by-minute basis, consistently asking the viewer to look at the world of underground money in the same overly-stylized way that its characters do. Williams’s lighting game is beyond effective, as he utilizes blues and purples to highlight black skin in ways that prophecy the coming of Girlhood, Magic Mike XXL, and Moonlight about 15 years later.

There are serious claims that could be legitimately weighed against the film in terms of glamorizing violence and the objectification of women (what else from the director of “Big Pimpin’”?), but it is also true that Belly has a deep sense of Old Testament judgement to it, not unlike its neon-cousin Only God Forgives (which I analyzed). The characters even have names like “Sincere,” “Knowledge,” “Wise,” and “Reverend Savior,” adding to the sense that what we’re really watching is a type of ancient morality play set in the glam-era of hip-hop culture. Whatever your take on the film is politically, one can’t deny its success as a piece of cinematic sensory overload in the vein of Spring Breakers and Tokyo Tribe. Whatever your feelings, I can guarantee you’ll crave more feature films made by music video visionaries. - Andrew Swafford

Ghost Dog (1999) by Jim Jarmusch

Though the list of movies featuring rappers is long and varied, there are still relatively few films that treat the genre with the serious consideration it deserves. Many of these films, like last year’s Straight Outta Compton, focus exclusively on free-styling instead of the difficult and arduous songwriting processes that often shape our favorite rap songs. In their article “Josephine Baker and Paul Colin: African American Dance Seen through Parisian Eyes,” Karen C. C. Dalton and Henry Louis Gates Jr. outline many of the myths held by Europeans about historically black art forms: “African creative expression was spontaneous, collective, instinctive, uncensored either internally or externally, free of rules, and in touch with potent, mysterious, nonrational, and subliminal forces.” Films about rap music often perpetuate these myths, choosing to depict the rapping as an act of spontaneous creation instead of serious consideration.

That’s where Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai, which features a soundtrack and brief appearance from the Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA, comes in. Jarmusch, maybe one of the whitest American directors working today, seems like an unlikely candidate to make an insightful movie about rap music, but surprisingly, Ghost Dog is one of the best films I’ve ever seen about the form. Ghost Dog pairs the RZA’s hip-hop soundtrack and references to rappers with a modern-day warrior who lives his life in line with the codes of ancient samurai.

Great rappers are like samurai, but with language as their swords. Like being a great samurai, being a great rapper means one must constantly harness and hone mental and creative agilities. The best rappers have never lived on talent alone. It takes constant, careful attention, and dedicated precision. Rap songs do not will themselves into being; they require as much work as painting, literature, or any other form of art. It might be more entertaining to see Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre spontaneously fall into a groove, like they do in Straight Outta Compton, but that’s not how it always works. Like the samurai hero of Ghost Dog, rappers need time and training to master their skills. - Nathan Smith

Bones (2001) by Ernest Dickerson

At the tail end of his career with Master P’s No Limit Records, the American rapper known as Snoop Dogg released a little horror film called Bones. A splendid, small-scale collaboration with Ernest Dickerson, the director known for the Tupac-starring Juice and his work as cinematographer on some of Spike Lee’s best movies, Bones is like an American take the work of Italian horror master Lucio Fulci, with plenty of maggots, bold colors, and other blood-boiling sights. Snoop Dogg plays the titular Bones, a dead pimp who was betrayed and murdered by his best friends and business associates because of his desire to keep drugs out of black neighborhoods. When a handful of idealistic kids attempt to renovate Bones’ old digs and turn it into a club, his spirit is set loose and he’s hungry for vengeance. Bones isn’t just a great horror movie; it’s also an homage to the Blaxploitation genre and stars Pam Grier, one of the icons of that subgenre, as Snoop Dogg’s former lover. Like many of the best entries in the Blaxploitation canon, Bones isn’t just a lot of genre fun; it’s surprisingly subversive, and works as a commentary on gentrification and the need to support black businesses. - Nathan Smith

Paid in Full (2002) by Charles Stone III

Crime and film have a long lasting relationship that goes back before feature lengths. While there has always been an emphasis on organized crime such as heists and mobs, these two movies see crime as a mean to an end, a way out of the entrapments of their poverty stricken surroundings. Cam’ron’s role in Paid In Full is similar to Tupac’s in Juice, two who get enveloped into the lifestyle of crime, and ultimately fall for taking things too far. Both are set in 80s Harlem and are about young black men who choose a life of crime because the only people they see “winning” are those collecting their funds illegally.

Cam’ron and Tupac’s roles both highlight their ambitious streaks, and showcases them as their downfall. This shows the cons off an “all in” mentality when the subject you’re exerting your efforts upon isn’t worth the time of day itself. In reality, Cam’ron and Tupac poured their ambitions into their art putting them in more successful places than the characters they portray.Paid in Full & Juice focus on the death of glamorous crime based on the Al Capone types of the world. Asks not if crime pays, but at what cost? - Malcolm Baum

Be Kind Rewind (2008) by Michel Gondry

Be Kind Rewind feels like the B-side of a record — a hidden gem that takes careful concentration to find. Or rather a luck-of-the-draw on streaming or at a video store.

Starring Jack Black and Mos Def, and directed by Michel Gondry, the film feels like something familiar but at the edge of our comfortable understanding. It features elements that we already know we enjoy — Jack Black being himself, Danny Glover's stern-faced delivery of comedic lines and a wholesome tale set in the outskirts of the big city — but matches it with boundless imagination that creates a universe unlike anything else.

Be Kind Rewind could be classified as just another one of the quirky indie flicks that feature twee characters doing oddball things, but it transcends this to be an endearing story of community.

The film follows Jerry (Black) and Mike (Mos Def) as two store clerks who work at a New Jersey-based video store in the age of DVDs. The VHS tapes that they provide are becoming outdated and the store, and its owner (Glover), are on the way out. A mistake by Jerry leads to the men discovering that all of the tapes were erased when the character came in “magnetized” after an accident at the power plant and forces them to re-enact every one of the movies to pass along to patrons — who love it.

The plot is schmaltzy and predictable, but Gondry keeps up engaged with how this community of outsiders come together to participate in a shared experience. In this way, the movie functions as our association with the art form as cinema itself can also work as a shared experience among many people.

And let’s hope that experience can be sweded as well. - Zach Dennis

Bright Star (2009) by Jane Campion

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art / Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night / And watching, with eternal lids apart…

So begins the poem “Bright Star” by 19th -century poet John Keats. The film bears the same name and follows Keats (Ben Whishaw) and Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish) as they fall in love tragically near the end of Keats’ life. Forces beyond their control seem to pull them apart. Keats is a poet and doesn’t make enough income to be a suitable husband for Fanny. Then, once it seems they’ve given up on following society’s rules, Keats falls ill. Bright Star is a real tear-jerker in the most sincere way. Whishaw and Cornish spin a lovely web of sadness for viewers to get wrapped up in, not to mention wear some pretty cool 19th century garb. Director Jane Campion adds her expertise to every aspect of the film.

Now, you are probably thinking that’s fine and everything, but how does this movie fit in this canon? Well, I’m glad you asked. Not only is Australian-native Abbie Cornish an amazing actress, she also has a rap career with the stage name “Dusk.” While this news is probably surprising (it definitely was for me), it isn’t the only reason I chose Bright Star for this canon.

Bright Star is about freedom of expression through poetry. Poetry is about using words to describe how you feel, and even though I’m not expert when it comes to rap music I can definitely see the commonalities between the two mediums. So check out Bright Star if you want to ugly cry or just to see rap star Dusk put on a stellar performance. - Jessica Carr

Spring Breakers (2012) by Harmony Korine

When my future child(ren) ask(s) me where babies come from, I will respond with, "Remind me ten years from now that I need to show you the movie Spring Breakers." Ten years later, they will do just that, and I will sit them down in front of the television set and pop this movie into whatever player will succed the Blu Ray. As the credits roll, my child(ren) will say to me, "Dad, that had nothing to do with the miracle of childbirth." They will be sorely mistaken, but I won't tell them. It is something they will have to realize on their own. Years down the road, when they have children of their own, they will be sitting at the kitchen table one evening, paying bills, when all of a sudden it will dawn on them. "Dad was right," they will say. And they will slowly saunter to their child(ren)'s room, flick on the light and say, "Remind me ten years from now that I need to show you the movie Spring Breakers." - Ben Shull

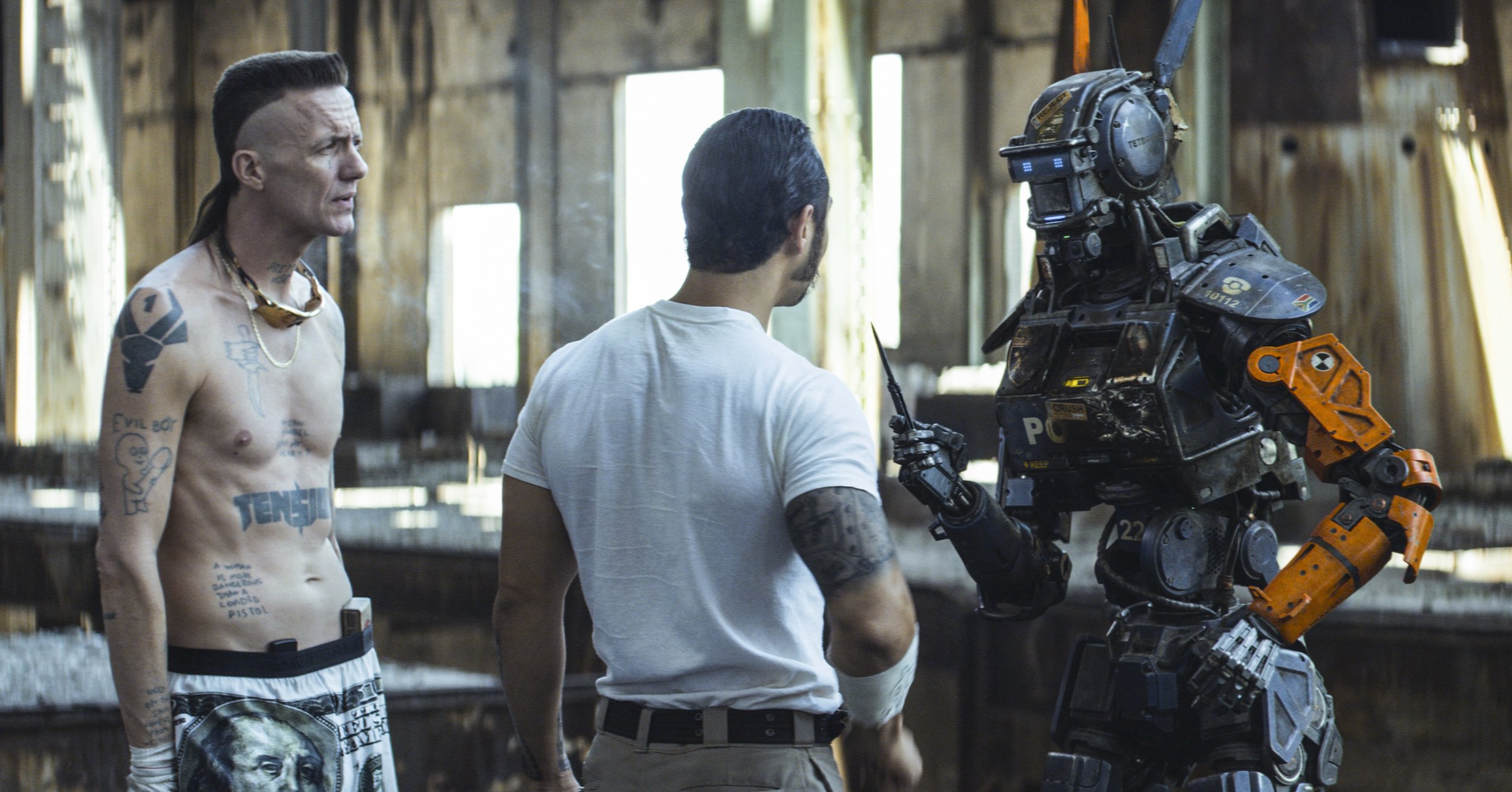

Chappie (2015) by Neill Blomkamp

I’m not sure how to classify Chappie.

Is it a comedy? I guess I laughed at it. Is it a drama? If you count crying Die Antwoord as one of them gets shot, then yes. Is it an action movie? That may be the best way to describe it.

The winning quality of Chappie for me is that it never really fits into any mold — just floating in cinematic space as this weird, unadulterated hodgepodge of insanity and entertainment. Director Neill Blomkamp adds elements of outcry for social issues, but they never really land as well as he wants them to.

Chappie is Chappie, and that works for me.

The film follows a sentient robot named Chappie (voiced by Sharlto Copley) that was created by a headstrong engineer played by Dev Patel. He has the admiration of his boss, Michelle Bradley (Sigourney Weaver), but she also recognizes that he may be off his rocker a bit and his rival, Vincent Moore (a mulleted Hugh Jackman) sees this as an opportunity to bring his latest invention to the foreground.

While they recently rebooted RoboCop, it would make more sense for Chappie to be the next link in that franchise’s chain as it carries similar through-lines of social issues, justice and questions of humanity that the 1987 possessed. Most of the more sentimental stuff feels tacked on, but this absurd attempt to tie humanity to this odd robot works for me.

I don’t think it answers any of the questions it poses, but it carries them out with such random absurdity that I can’t help but applaud it. Near the end of the movie, Chappie comes to the realization that he is what he is, and I think the movie does as well. - Zach Dennis

Dope (2015) by Rick Famuyiwa

I remember when the first trailer came out for Dope. It was upbeat and seemed like a movie that I would like. Now staring at the Dope poster that hangs on my bedroom wall I can see that my instincts were right. The coming of age drama follows Malcolm (Shameik Moore), a geek obsessed with 90’s hip hop culture, living in an impoverished neighborhood in Inglewood, California. Malcolm is a good high school student with a dream to attend Harvard. Diggy (Kiersey Clemons) and Jib (Tony Revolori) make up Malcolm’s dorky posse. The oddballs seem out of place in the 21st century which results in them getting teased a lot at school. The trio find solace in their band “Awreeoh,” which leads to the film’s very catchy soundtrack made up of original songs written by Pharrell Williams and a variety of old school hip hop tracks by names like Public Enemy, Naughty by Nature, and Nas. Malcolm seems to have everything figured out, until he gets mixed up with drug dealer Dom (A$AP Rocky) and the conflict escalates from there.

Overall, Dope has a lot of qualities that I like in a film. Awesome performances, fun music, and loveable characters make it a watchable movie. For some critics, the tone of Dope is all over the place. Much like Malcolm, I think director Rick Famuyiwa was trying to fuse a lot of his interests together. He wanted to pay homage to nostalgic hip hop while making a political statement about current events. However, for some people the concept was nice, but the execution fell a little short. I still enjoyed Dope and will continue to watch this movie because it’s d…. okay, I won’t say it. - Jessica Carr